The Anatomy of an Atom

If matter is composed of atoms, what are atoms composed of? Are they the smallest particles, or is there something smaller?

Discovering the Inside of an Atom

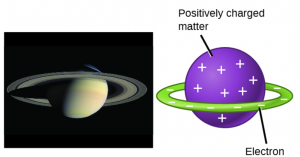

In the late 1800s, scientists began to investigate the particles that exist inside of an atom. The first particle to be discovered within atoms was the electron, an extremely tiny particle with a negative charge (charge = -1). Experimental evidence for these particles helped scientist develop models of the inside of the atom. One prescient model for the atom was proposed in 1903 by Hantaro Nagaoka, who postulated a Saturn-like atom, consisting of a positively charged sphere surrounded by a halo of electrons.

In the following years, experiments by Ernest Rutherford confirmed that a small, relatively heavy, positively charged body must be at the center of each atom. This positively charged body was named the nucleus of the atom. In Rutherford’s model of the atom, the small, positively charged nucleus contains most of the mass of the atom, and is surrounded by the negatively charged electrons. The negatively charged electrons orbit around the nucleus because they are attracted to the positive charge in the nucleus (opposite charges attract). They also balance out the charge of the nucleus so that the atom is electrically neutral (total charge equals zero).

Further experiments revealed that the nucleus contains two types of particles: protons and neutrons. A proton is a positively charged particle (charge = +1) with a mass of 1 atomic mass unit (amu). (The atomic mass unit (amu) is an extremely small unit of mass used to keep track of the mass of protons and neutrons in atoms.) Protons are incredibly small, however, their mass is about 2,000 times greater than the mass of an electron. A neutron is an uncharged (neutral, charge = 0) particle with a mass approximately the same as that of a proton (1 amu).

The nucleus contains the majority of an atom’s mass because protons and neutrons are much heavier than electrons, whereas electrons occupy almost all of an atom’s volume. For a perspective about the relative sizes of an atom and its nucleus, consider this: If the nucleus were the size of a blueberry, the atom would be about the size of a football stadium! Most of the volume within an atom consists of empty space!

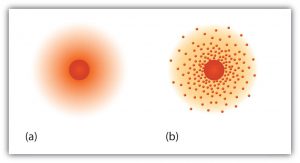

The “planetary” model described above is essentially the same model that we use today to describe atoms but with one important modification. The planetary model suggests that electrons occupy certain specific, circular orbits about the nucleus. We know now that this model is overly simplistic. A better description is that electrons form fuzzy clouds around nuclei. The figure below shows a more modern version of our understanding of atomic structure.

Summary of the Three Subatomic Particles: Electron, Proton, and Neutron

We now understand that all atoms consist of three subatomic particles: protons, neutrons, and electrons. The table below lists some of their important characteristics:

| Name | Location | Charge | Mass (amu) |

| electron | outside nucleus | -1 | ~0 (much smaller than 1) |

| proton | nucleus | +1 | 1 |

| neutron | nucleus | 0 | 1 |

You can build your own atoms and investigate their properties using this interactive simulation! Build an Atom

Attributions

This page is based on “Chemistry 2e” by Paul Flowers, Klaus Theopold, Richard Langley, William R. Robinson, PhD, Openstax which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/chemistry-2e/pages/1-introduction

This page is based on “Chemistry of Cooking” by Sorangel Rodriguez-Velazquez which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Access for free at http://chemofcooking.openbooks.wpengine.com/

This page is based on “The Basics of General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry” by David W Ball, John W Hill, Rhonda J Scott, Saylor which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Access for free at http://saylordotorg.github.io/text_the-basics-of-general-organic-and-biological-chemistry/index.html