Physical vs. Chemical Properties and Changes

Part of understanding matter is being able to describe it. One way we describe matter is to assign properties of matter to different categories. The properties that chemists use to describe matter fall into two general categories: physical and chemical.

Physical Properties and Changes

Physical properties are inherent characteristics that describe matter. They include characteristics such as size, shape, color, mass, density, hardness, melting and boiling points, and conductivity. Some physical properties, such as density and color, may be observed without changing the phase of the matter. Other physical properties, such as the melting point of iron or the freezing point of water, can only be observed as matter undergoes a phase change (melting or freezing).

A physical change is a change in the properties or phase of matter without any accompanying change in the chemical identities or compositions of the substances contained in the matter. For example, when water freezes to form ice, there is no change to the chemical identity of the water. Water is water regardless of whether it is in solid or liquid form. The molecules will consist of one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms, both in solid ice and liquid water.

Physical changes are observed when butter melts, when sugar dissolves in coffee, and when steam condenses into liquid water. Other examples of physical changes include magnetizing and demagnetizing metals (as is done with common antitheft security tags) and grinding whole spices into powders (which can sometimes yield noticeable changes in color). In each of these examples, there is a change in the phase, form, or properties of the substance, but no change in its chemical identity or composition.

Physical changes include all the phase changes defined in the section “Matter and its Phases”:

| Change | Name |

| solid to liquid | melting, fusion |

| solid to gas | sublimation |

| liquid to gas | boiling, evaporation |

| liquid to solid | solidification, freezing |

| gas to liquid | condensation |

| gas to solid | deposition |

Special Section: Viscosity and Chocolate

Viscosity is a physical property that describes the way a substance flows. The term viscous means “sticky”. Chocolate comes in various viscosities, achieved by mixing different ingredients into the chocolate. Mixing ingredients into chocolate is a physical change because although the physical properties of the chocolate change (viscosity, perhaps color), the chemical identities and compositions of the substances in the chocolate do not change.

Chocolate manufacturers mix chocolate so that it has the appropriate viscosity for their needs. The amount of cocoa butter in the chocolate is largely responsible for the viscosity level. Emulsifiers like lecithin can help thin out melted chocolate, so it flows evenly and smoothly. Because it is less expensive than cocoa butter at thinning chocolate, lecithin can be used to help lower the cost of chocolate.

Molded pieces such as Easter eggs require a chocolate of less viscosity. That is, the chocolate should be somewhat runny so it is easier to flow into the moulds. This is also the case for coating cookies and most cakes, where a thin, attractive and protective coating is all that is needed. A somewhat thicker chocolate is advisable for things such as ganache and flavoring of creams and fillings.

Some recipes require alterations to store-bought chocolate to decrease its viscosity. A vegetable oil is sometimes used to thin melted chocolate for a thin, even coating on squares or bar cookies. This also makes them easier to cut after the chocolate has cooled.]

Chemical Properties and Changes

Chemical properties are characteristics that describe how matter changes its chemical identity or composition (or resists changes to its chemical identity or composition). An example of a chemical property is flammability—a material’s ability to burn—because burning changes the chemical composition of a material. When we burn a flammable gas like methane on a gas stove, the methane is converted to carbon dioxide and water, with the help of oxygen and heat. Chemical changes that involve burning of a substance are often called combustion reactions.

Other examples of chemical properties include toxicity, acidity, and many other types of reactivity. Sometimes we compare the chemical properties of different substances to help us decide how we will use them. For example, when comparing cast-iron versus stainless steel skillets, the cast-iron version will be more susceptible to rust when exposed to oxygen and water.

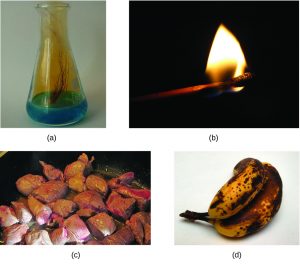

A chemical change is a change in the chemical identities or compositions of the substances contained in the matter. A chemical change always produces one or more types of matter that differ from the matter present before the change. The formation of rust is a chemical change because rust is a different kind of matter than the iron, oxygen, and water present before the rust formed. The burning of methane is a chemical change because the gases produced are very different kinds of matter from the original gas, methane. Other examples of chemical changes include reactions that are performed while cooking (such as baking cookies or browning a steak), all forms of combustion (burning), fermentation, and food being digested or rotting.

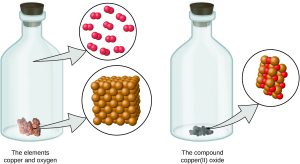

Atoms are neither created nor destroyed during a chemical change, but are instead rearranged to yield substances that are different from those present before the change (see figure below).

Attributions

This page is based on “Chemistry 2e” by Paul Flowers, Klaus Theopold, Richard Langley, William R. Robinson, PhD, Openstax which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/chemistry-2e/pages/1-introduction

This page is based on “Chemistry of Cooking” by Sorangel Rodriguez-Velazquez which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Access for free at http://chemofcooking.openbooks.wpengine.com/

This page is based on “The Basics of General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry” by David W Ball, John W Hill, Rhonda J Scott, Saylor which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Access for free at http://saylordotorg.github.io/text_the-basics-of-general-organic-and-biological-chemistry/index.html