Ions

In Chapter 2, we learned that atoms are composed of three subatomic particles: protons, neutrons, and electrons. Protons and neutrons exist in the nucleus of the atom, while electrons exist outside the nucleus. Protons are positive (charge = +1), electrons are negative (charge = -1), and neutrons are neutral (charge = 0).

How many electrons are in an atom of a pure element? Previously we stated that for a neutral atom (total charge = 0), the number of electrons equals the number of protons, so the total opposite charges cancel. Thus, the atomic number of an element gives the number of protons and the number of electrons in a neutral atom of that element.

The number of protons in an atom (and thus the identity of the atom) does not change in physical processes or chemical reactions. Electrons, however, can be added to atoms by transfer from other atoms, lost by transfer to other atoms, or shared with other atoms. The number of electrons in an atom changes when the atom forms a chemical bond with another atom. Many chemical reactions involve transferring of electrons from one atom to another.

During the formation of some compounds, atoms gain or lose electrons, and form electrically charged particles called ions. Ions have different numbers of protons and electrons, thus they will no longer be electrically neutral. The charge of an ion can be determined as follows:

charge = number of protons − number of electrons

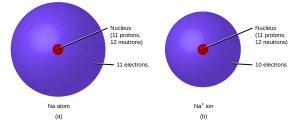

Positively charged atoms called cations (pronounced CAT-eye-ons) are formed when an atom loses one or more electrons. Most metals can lose electrons to form cations. For example, a neutral sodium atom (atomic number = 11) has 11 electrons. If this atom loses one electron, it will become a cation with a 1+ charge (11 − 10 = +1).

An atom that gains one or more electrons will exhibit a negative charge and is called an anion (pronounced ANN-eye-ons). Most nonmetals can gain electrons to form anions. For example, a neutral oxygen atom (atomic number = 8) has eight electrons, and if it gains two electrons it will become an anion with a −2− charge (8 − 10 = −2).

You can use this simulation to build charged ions with different numbers of protons and electrons.

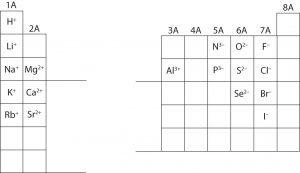

The following figure shows examples common ion charges of some elements.

Example: Identifying Cations and Anions

Identify each as a cation, an anion, or neither.

- H+

- Cl−

- O2

- Ba2+

- CH4

- NH3

Solution

- H+ has a positive charge, thus it is a cation.

- Cl− has a negative charge, thus it is an anion.

- O2 has no overall charge, thus it is neutral. It is neither.

- Ba2+ has a positive charge, thus it is a cation.

- CH4 has no overall charge, thus it is neutral. It is neither.

- NH3 has no overall charge, thus it is neutral. It is neither.

Example: Identifying Ions and Determining Charge

- An ion found in some compounds used as antiperspirants contains 13 protons and 10 electrons. What is its symbol and charge? Is it a cation or anion?

- Give the symbol and charge for the ion with 34 protons and 36 electrons. Is it a cation or anion?

Solution

- Because the number of protons remains unchanged when an atom forms an ion, the atomic number of the element must be 13. Knowing this lets us use the periodic table to identify the element as Al (aluminum). The Al atom has lost three electrons and thus has three more positive charges (13) than it has electrons (10). The charge is determined as follows:

charge = number of protons − number of electrons

charge = 13 – 10 = +3

Thus, this is the cation, Al3+.

2. Because the number of protons remains unchanged when an atom forms an ion, the atomic number of the element must be 34. Knowing this lets us use the periodic table to identify the element as Se (selenium). The Se atom has gained two electrons and thus has two more negative charges (36) than it has protons (34). The charge is determined as follows:

charge = number of protons − number of electrons

charge = 34 – 36 = -2

Thus, this is the anion, Se2-.

Attributions

This page is based on “Chemistry 2e” by Paul Flowers, Klaus Theopold, Richard Langley, William R. Robinson, PhD, Openstax which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/chemistry-2e/pages/1-introduction

This page is based on “The Basics of General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry” by David W Ball, John W Hill, Rhonda J Scott, Saylor which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Access for free at http://saylordotorg.github.io/text_the-basics-of-general-organic-and-biological-chemistry/index.html