Lesson 3: Calipers

Tool Names

Tool Names

Reading

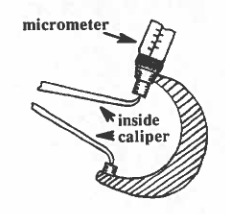

A caliper is any instrument which has two legs (or jaws) which are fastened together at one end and which is used to measure the diameter or thickness of something. In the picture from the vocabulary sheet, there is an outside caliper: It has two curved legs fastened together at the top; the jaws can be opened or closed to various thicknesses with an adjusting nut which is turned by hand.

A caliper is any instrument which has two legs (or jaws) which are fastened together at one end and which is used to measure the diameter or thickness of something. In the picture from the vocabulary sheet, there is an outside caliper: It has two curved legs fastened together at the top; the jaws can be opened or closed to various thicknesses with an adjusting nut which is turned by hand.

The caliper cannot be read directly, so a rule is used to measure the distance between the points of the two jaws. When the machinist is making many parts he/she may want to set a caliper to a rule, i.e., to open the jaws a certain length with the use of a rule, so that the caliper is set to measure the length of some outside caliper important dimension on the part. Then the caliper can be used over and over again as a quick test to see if the dimension is correct. This method allows accuracy to within .007 in. If more accurate measurement is needed, the machinist should use a different instrument. The outside caliper can be used to measure both round pieces and flat pieces.

There is also an inside caliper which has the points of the jaws pointing outward and which can be inserted into holes to measure inside diameters, etc. To take a reading from it, an outside micrometer can be used. An inside caliper can also be set to a certain length; an outside micrometer is used to set the caliper.

There is also an inside caliper which has the points of the jaws pointing outward and which can be inserted into holes to measure inside diameters, etc. To take a reading from it, an outside micrometer can be used. An inside caliper can also be set to a certain length; an outside micrometer is used to set the caliper.

Quick True/False Questions

VERNIER CALIPER

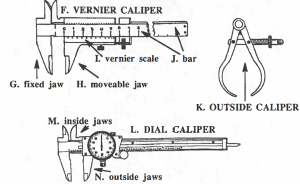

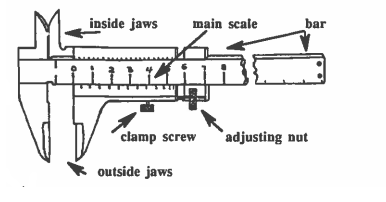

The vernier caliper, shown at the right is used for measuring diameters and thicknesses. It has fixed jaws at the left of the movable jaws at the right; it has inside jaws at the top and outside jaws at the bottom. It has a vernier scale and a bar on which the jaws move. The reading can be made more accurate with the fine adjusting nut which can be used to make the jaws more snug around the thing being measured. A clamp screw can be used to lock the reading in place.

The vernier caliper, shown at the right is used for measuring diameters and thicknesses. It has fixed jaws at the left of the movable jaws at the right; it has inside jaws at the top and outside jaws at the bottom. It has a vernier scale and a bar on which the jaws move. The reading can be made more accurate with the fine adjusting nut which can be used to make the jaws more snug around the thing being measured. A clamp screw can be used to lock the reading in place.

The vernier scale can have either 25 or 50 divisions; the number of these divisions will always be one more than the divisions which divide up the same length on the main scale: 25 divisions on the vernier scale will be next to 24 divisio0ns on the main scale; or 50 divisions on the vernier scale will be next to 49 divisions on the main scale. In taking a vernier scale reading, always look for the line on the vernier scale which exactly matches a line on the main scale; then read off the vernier number – this will be .001 digit in the answer. Readings are accurate to the nearest thousandth of an inch.

Of course, there are also metric vernier calipers, which measure thicknesses in millimeters and subdivisions of the millimeter down to .02 mm on the vernier scale.

Quick True/False Questions

DIAL CALIPER

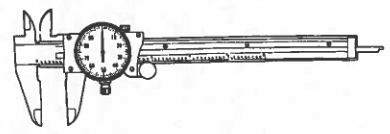

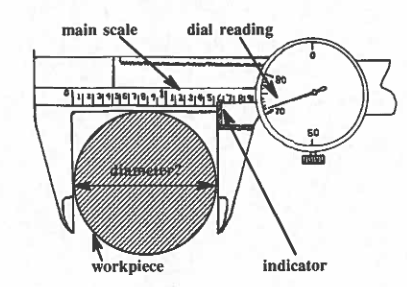

The dial caliper is replacing the vernier caliper as a measuring instrument, because of the dial from which a direct reading of thousandths can be taken. There is less chance of error in reading from the dial than there is in trying to judge which one of 50 vernier lines exactly matches a line on the main scale.

The dial caliper is replacing the vernier caliper as a measuring instrument, because of the dial from which a direct reading of thousandths can be taken. There is less chance of error in reading from the dial than there is in trying to judge which one of 50 vernier lines exactly matches a line on the main scale.

The dial caliper has many of the features of the vernier caliper, but has no vernier scale. Instead it has a dial with a moving arrow which measures thousandths from .000 to .100; each mark on the dial is equal to .001 inch. The movable jaw is moved along the scale by an adjusting nut or by a thumb pad made of knurled black plastic. A knurled screw at the top of the caliper can be used to lock a reading in place by tightening the screw. Another knurled screw at the bottom of the dial can be used to adjust the arrow, so that it is exactly on zero before a reading is taken. The dial caliper has inside jaws at the top and outside jaws at the bottom.

Quick True/False Questions

Now is the time to take out the dial caliper and look at it carefully. See if you can find all the parts from the above paragraph. If you don’t have the caliper, check it out now.

How to Read the Dial Caliper: The caliper’s main scale is divided into tenths of an inch. Follow these steps to read a dial caliper:

Step One: Put the object to be measured between the outside jaws.

Step Two: Read the number of inches and tenths of an inch shown by the indicator. (This will give you a whole number and the first digit after the decimal point.)

Step Three: Read the number of thousandths off the dial. (This will give you the second and third digits after the decimal point.)

Let’s look at the example below: There is a piece of round work in the jaws of the dial caliper. What is the diameter? We read the numbers off the caliper, using the steps just listed.

| STEPS | READING |

| Step One: The workpiece is secured in the caliper. | |

| Step Two: The main scale shows 1 whole inch and .5 of another. | 1.500 |

| Step Three: The arrow on the dial points to 71 thousandths. | 0.071 |

| ANSWER: 1.571 |

NOTE: You should be able to look at the micrometer and read off the numbers without any addition. Remember: The main scale gives us the whole and the first digit of a three-digit decimal. The dial reading gives us the last two digits of the three-digit decimal.

MAKING FRIENDS AT WORK

Listen to Making Friends at Work. Practice with a partner.

Conversation No. 1 (Jose and Bill are eating together at lunch.)

Jose: Hi, Bill! How was your weekend?

Bill: It was O.K. I did some work around the house, and we took the kids to the movies.

Jose: Oh, what movie did you see?

Bill: It was a Disney film—their latest. The kids liked it.

Jose: My wife and I take our kids to the movies sometimes. It’s a good place to learn English.

Bill: I never thought of that. I suppose you could pick up a lot of the lingo, just listening.

Jose: Maybe our families could go together some time.

Bill: Yeah, that’d be great. You met my wife at the Christmas party, and I remember meeting yours.

Jose: Well, lets keep our eyes peeled for a good one.

Bill: Sure enough! I think everybody would enjoy that.

MAKING FRIENDS WORK (continued)

Conversation No. 2: (Mona and Liz are talking during a break.)

Mona: I love your sweater, Liz. Is that something new?

Liz: No, Frank gave it to me for Christmas last year. It’s usually too warm to wear it.

Mona: I think it’s really cute–I like the color, and it’s nice and long.

Liz: Yeah, before we moved here from Colorado, I used to wear a lot of sweaters in the winter.

Mona: My family is originally from the mountains in Central Mexico. We never had snow, but it could get very chilly at night. We wore heavy shawls.

Liz: I’ve seen some of those shawls down in Tijuana. They looked like they’d be very warm.

Mona: So, you’ve been to Mexico before?

Liz: I’ve only been to Tijuana and Ensanada. Frank and I would like to see more of the country, but we don’t get around to it.

Mona: Well, our family goes every year to Guadalajara to visit my parents. Maybe you’d like to come with us some time.

Liz: Oh, that would be great! We’re a little bit afraid to travel by ourselves in a country where we don’t speak the language.

Mona: That wouldn’t be a problem, if you came with us.

Liz: That’s what I’m thinking. Let’s get after work and talk about it more.

Note: In the two conversations, you can see some ways of making good conversation: (1) ask other people about themselves and their families; (2) listen to what they say and respond to that; (3) tell them about yourself; (4) say good things about them, what they’re wearing, the way they work—that’s called giving a compliment. Talk with your teacher; discuss why making friends at work is important.