13 Doing Work

Lawrence Davis

We started the previous unit with a discussion of Jolene's motion during a shift on the medical floor of a hospital, including all the starts and stops that she makes. When Jolene is standing still she has zero kinetic energy. As she takes a step to begin walking she now has kinetic energy. Jolene had to supply that energy from within herself. When Jolene comes to a stop her kinetic energy is transferred to thermal energy by friction. When she begins walking again she will need to supply the new kinetic energy all over again. Even if Jolene walks continuously, every step she takes involves two inelastic collisions (the push-off and the landing) so kinetic energy is constantly being transferred to thermal energy. To stay in motion Jolene has to re-supply that kinetic energy. Walking around all shift uses up Jolene's stored energy and that is why she gets tired.

Work

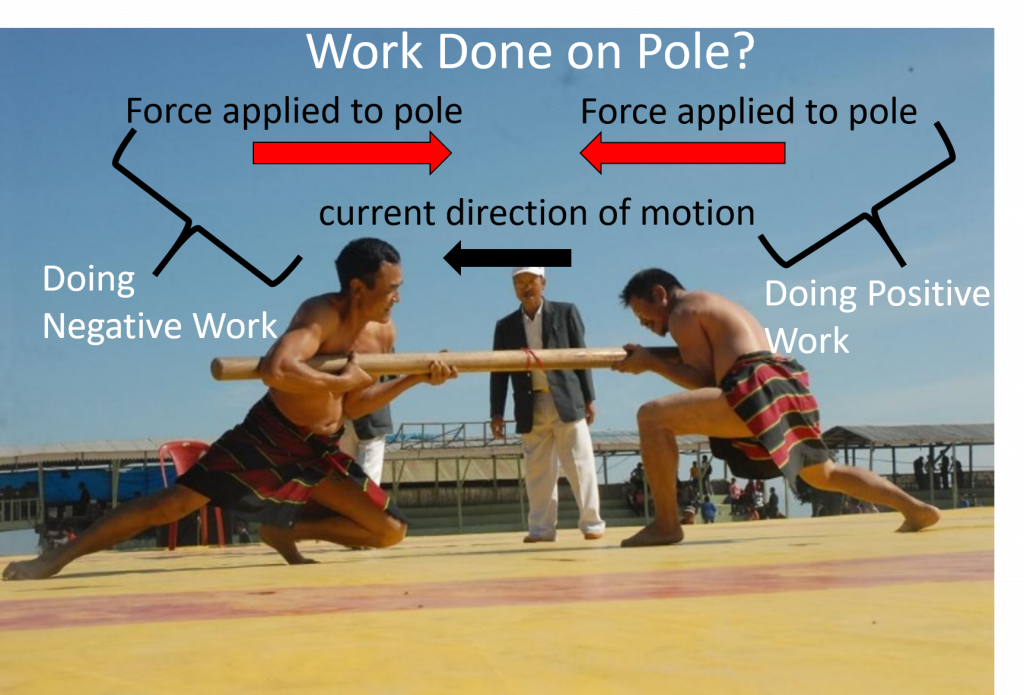

The amount of energy transferred from one form to another and/or one object to another is called the work. Doing work is the act of transferring that energy. Doing work requires applying a force over some distance. The sign of the work done on an object determines if energy is transferred in or out of the object. For example, the athlete on the right is doing positive work on the pole because he is applying a force in the same direction as the pole's motion. That will tend to speed up the pole and increase the kinetic energy of the pole. The athlete on the left is doing negative work on the pole because the force he applies tends to decrease the energy of the pole.

The positive or negative sign of the work refers to energy transferring in or out of an object rather than to opposite directions in space so work is not a vector and we will not make it bold in equations.

Calculating Work

The actual amount of work done is calculated from a combination of the average force and the distance over which it is applied, and the angle between the two:

[latex]\begin{equation} W = Fdcos\theta \end{equation}[/latex]

Everyday Example: Lifting a Patient

Jolene works with two other nurses to lift a patient that weighs 867 N (190 lbs) a distance of 0.5 m straight up. How much work did she do? Assuming Jolene lifted 1/3 of the patient weight, she had to supply an upward force of 289 N. The patient also moved upward, so the angle between force and motion was 0°. Entering these values in the work equation:

[latex]\begin{equation*} W = Fdcos\theta = (289{N})(0.5{m})cos(0^{\circ}) = 144{Nm} \end{equation*}[/latex]

We see that work has units of Nm, which are called a Joules (J). Work and all other forms of energy have the same units because work is an amount of energy, but work is not a type of energy. When calculating work the costheta accounts for the force direction so we only use the size of the force (F) in the equation, which is why we have not made force bold in the work equation.

The [latex]cos\theta[/latex] in the work equation automatically tells us whether the work is transferring energy into or out of a particular object:

- A force applied to an object in the opposite direction to its motion will tend to slow it down, and thus would transfer kinetic energy out of the object. With energy leaving the object, the work done on the object should be negative. The angle between the object's motion and the force in such a case is 180° and [latex]cos(180^{\circ}) = -1[/latex], so that checks out.

- A force applied to an object in the same direction to its motion will tend to cause it to speed up, and thus would transfer kinetic energy in to the object. With energy entering the object, the work done on the object should be positive. The angle between the object's motion and the force in such a case is 0° and [latex]cos(0^{\circ}) = 1[/latex] so that also checks out.

- Finally, if a force acts perpendicular to an objects motion it can only change its direction of motion, but won't cause it to speed up or slow down, so the kinetic energy doesn't change. That type of force should do zero work. The angle between the object's motion and the force in such a case is 90° and [latex]cos (90^{\circ}) = 0[/latex] so once again, the [latex]cos\theta[/latex] in the work equation gives the required result. For more on this particular type of situation read the chapter on weightlessness at the end of this unit.

The work equation gives the correct work done by a force, no matter the angle between the direction of force and the direction of motion, even if the force points off at some angle other than 0°, 90°, or 180°. In such a case, some part of the force will be doing work and some part won't, but the [latex]cos\theta[/latex] tells us just how much of the force vector is contributing to work.

Reinforcement Exercises

Davis, Lawrence. Body Physics: Motion to Metabolism. Open Oregon Educational Resources. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/bodyphysics

- Adapted from Insuknawr (Rod Pushing Sport by H. Thangchungnunga [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], from Wikimedia Commons ↵

- Image and associated practice problem were adapted from "This work" and by BC Open Textbooks is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

energy which a body possesses by virtue of being in motion, energy stored by an object in motion

energy that is caused by motion of the particles within the object or system related to its temperature

the resistance that one surface or object encounters when moving over another

the energy transferred to or from an object via the application of force along a displacement

any interaction that causes objects with mass to change speed and/or direction of motion, except when balanced by other forces. We experience forces as pushes and pulls

the force of gravity on on object, typically in reference to the force of gravity caused by Earth or another celestial body

at an angle of 90° to a given line, plane, or surface