7.3 Writing the Draft

Preview

This section of Ch. 7 will cover the following topics:

- turning the thesis and outline into a draft

- using topic sentences to generate content

- choosing a title

Most documents are composed of three specific types of paragraphs: introductory paragraphs, body paragraphs, and concluding paragraphs. This is true of a short story, a scientific study, a business report, and a college essay or research paper.

All paragraphs focus on a single idea and provide details that explain or illustrate. But introductions, body paragraphs, and conclusions have very different purposes.

Introductory Paragraphs

Your introduction is an invitation to your readers to consider what you have to say and then to follow along as you expand your point. If your introductory paragraph is dull or unfocused, your reader will not care about continuing.

The introductory paragraph’s job is to attract the reader’s interest and present the topic and the writer’s opinion about the topic (this is called the “thesis”). In a long paper, an introduction might also supply necessary background information or preview major points.

When writing an introductory paragraph, your main goals are to be interesting and clear. Following are several techniques for strong introductory paragraphs:

- Begin with a broad, general statement of the topic, narrowing to the thesis. For example: “Voting is a responsibility, but one that is not always easy to accomplish…” Add some detail, then end with the thesis: “Mail-in ballots would make voting cheaper, easier, and less prone to fraud.”

- Start with an idea or a situation the opposite of the one you will develop. For example: “In some countries, people have to risk their lives to cast a vote. In the U.S., it is usually just inconvenient.” Add detail that leads to the thesis.

- Convince the readers the subject applies to them or is something they should know about. For example: “Conversations about politics happen on the bus, at the dinner table, in the classroom. One topic of concern is voter turnout.” Add detail that leads to the thesis.

- Use an incident or brief story–something that happened to you or that you heard about. For example: “I remember the first time I voted.” Add more details, then end with the thesis: “Everyone should have the same chance I had to cast their vote. Mail-in ballots would help.”

- Ask questions so the reader thinks about the answers or so you can answer the questions. For example: “How many people complain about politics? Why do they just talk? Why don’t they vote? Mail-in ballots would make voting easier for many people.”

- Use a quotation to add someone else’s voice to your own. For example: “Franklin D. Roosevelt once said, ‘Nobody will ever deprive the American people of the right to vote except the American people themselves and the only way they could do this is by not voting.’ A key objective in a democracy, then, is to make it easy to vote. Mail-in ballots would do that.”

Notice that each technique starts with some sort of hook to grab the reader’s attention, follows with details, then ends with the thesis. An effective introduction stimulates the audience’s interest, says what the essay is about, and motivates readers to keep reading. It ends with a thesis that presents the main point of the essay.

Body Paragraphs

A body paragraph is just like the stand-alone paragraphs we worked on in Ch. 6.2, except most body paragraphs end with a transition to the next paragraph or begin with a transition from the previous paragraph (one or the other, never both!).

Topic sentences are vital to body paragraphs because they tie the paragraph to your thesis and remind readers what your essay is about. A paragraph without a clearly identified topic sentence will feel unfocused and scattered.

The information in body paragraphs should do the following:

- Be specific. The main points you make and the examples you use to expand on those points need to be clear and detailed. General examples are not nearly as compelling or useful because they are too obvious and typical. To say “students worry about exams” is not as effective as saying “the average community college student often feels overwhelmed during finals week.”

- Be selective. When faced with lots of information that could be used to prove your thesis, you may think you need to include it all. Effective writers resist the temptation to overwhelm. Choose wisely. If you have five reasons why exercise programs fail, pick the best three

Body paragraphs each begin with a topic sentence that states the main idea of the paragraph and connects that idea to the thesis statement. That is followed by supporting details (facts, examples, explanations) that develop or explain the topic sentence.

Concluding Paragraphs

Conclusions are more than just stopping. A strong concluding paragraph should convey a sense of completeness or closure. What do you conclude based on the points you made? Leave a good final impression.

There are several ways to write an effective conclusion:

- Philosophize. What does this all mean? End with a thought-provoking insight that asks your reader to think further about what you have written–why the subject is important, what should be done, what choice should be made.

- Synthesize, but don’t summarize and don’t repeat yourself. Show the reader how the points you made fit together.

- Predict (what may happen) or make a recommendation (what should be done). Help your reader see the topic differently.

It might be easier to consider what NOT to do in a conclusion:

- Do not use the phrase “In conclusion.” Readers can see that your essay is about to end. You don’t have to point it out. That is a clumsy transition.

- Do not simply restate your original point. You have referred to it throughout the paper; repeating it one more time can actually be annoying to the reader.

- Do not introduce a new idea. A conclusion can expand the reader’s sense of the topic, but it shouldn’t jump to a different topic altogether.

- Do not make sentimental, emotional appeals. If your argument is well-argued, the reader already agrees with you (or at least has agreed to consider your point).

- Do not directly address the reader. An essay is written for the general reader. Do not use “you.” If you want to claim your position, say “I.” If you want the reader to feel included, say “we.” If you want to look objective, say “most people” or “students in college.”

Think of an essay like this:

introduction + body paragraphs = conclusion

The equal sign is important. Your point and your support should lead to the conclusion, just like 2 + 2 = 4.

An effective conclusion reinforces the thesis and leaves the audience with a feeling of completion.

Step 3: Drafting

Drafting is the stage of the writing process when you develop the first complete version of the document.

The Body Comes First

Although many students assume an essay is written from beginning to end in one sitting, most well-written essays are built one section at a time, not necessarily in order, and over several sessions.

Write the body of your essay first, before you write the introduction.

This may seem odd. Why write the middle before the beginning? Because the body of your essay IS the essay. Think of the introduction and conclusion as an appetizer and dessert for the main course. The body of your essay is the meat, potatoes, and vegetables. How can you write an introduction if you don’t yet know what you are going to introduce? Write the body first.

The body of your essay is where you explain, expand upon, detail, and support your thesis. Each point in your outline can be turned into a topic sentence, which then becomes a paragraph or two by adding details that clarify and demonstrate your point.

Work on the body of your essay in several separate sessions. You’ll be surprised the kind of changes you want to make to something you wrote yesterday when you look at it again today. Keep working on the body until it says what you want.

Exercise 1

Using the thesis and outline you created in Ch. 7.2 and following the instructions above, write the body of your essay.

Before you finish, review the information in Ch. 6 on topic sentences, supporting ideas, and transitions. Be sure that information is reflected in your body paragraphs.

Then move on to the next step.

Write the Introduction Second

The introductory paragraph attracts the reader’s interest and presents the thesis. In a long paper, it can also supply any necessary background information or preview major points.

Read through the body of your essay one more time and think about what you could say to invite your reader in. How could you make the reader curious? As with the body, schedule at least two sessions to write your introduction. Coming back to reconsider what you’ve said gives you a new perspective.

Exercise 2

Write your introductory paragraph.

- Decide which technique from the list above would work best to introduce your essay.

- Draft your introduction, starting with a hook and ending with your thesis.

Work on your introductory paragraph until it is clear, focused, and engaging. Insert it before your body paragraphs.

Then move on to the next step.

The Conclusion Is Next

Once you have put together your body paragraphs and attached your introduction at the beginning, it is time to write a conclusion. It is vital to put as much effort into the conclusion as you did for the rest of the essay. A conclusion that is unorganized or repetitive can undercut even the best essay.

A conclusion’s job is to wrap the essay up so the reader is left with a good final impression. A strong concluding paragraph brings the paper to a graceful end.

Exercise 3

Write a concluding paragraph for your essay. Check the guidance on what a conclusion should do. Work on your conclusion until it is clear, focused, and engaging. Insert it after your body paragraphs.

Then move on to the next steps.

The Title

Titles are a brief and interesting summary of what the document is about. Titles are generally more than one word but no more than several words. Like the headline in a newspaper or magazine, an essay’s title gives the audience a first peek at the content. If readers like the title, they are likely to keep reading.

Go to Ch. 8 and look at the titles of the essays listed there. Notice which ones are both engaging and informative.

Caution: Don’t be too clever with a title. A clear title is better than something creative but confusing. Also, remember that “Essay 1” is not a title.

Adding Formatting

Once your draft is written, the document should be formatted. The format of a document is how it is laid out, what it looks like.

An instructor, a department, or a college will often require students to follow a specific formatting style. The most common styles are APA (American Psychological Association) and MLA (Modern Language Association). Guides like Diana Hacker’s A Pocket Style Manual and websites like the Purdue Online Writing Lab can help you understand how formatting works. Most writing classes, including this one, use MLA.

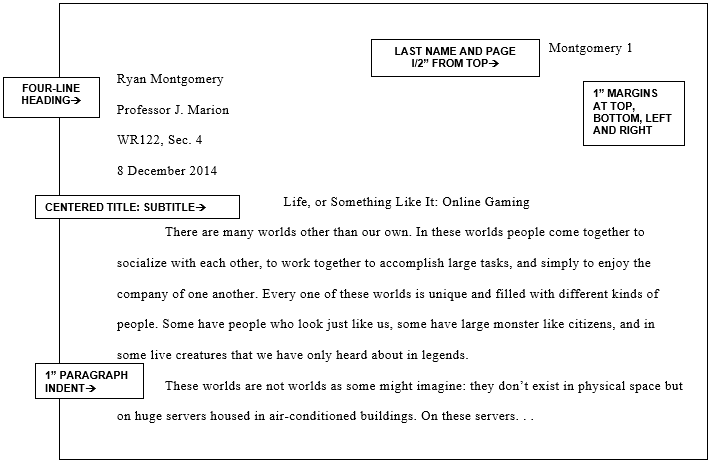

Below is an example of MLA formatting: Here is an explanation of the formatting example above:

Here is an explanation of the formatting example above:

- Use standard-sized paper (8.5” x 11”).

- Double-space all of the paper, from the heading through the last page.

- Set the document margins to 1” on all sides.

- Do not use a title page unless requested to do so by your instructor.

- Create a running header with your last name and the page number in the upper right-hand corner, 1” from the top and aligned with the right margin. Number all pages consecutively.

- List your name, the instructor’s name and title, the course name and section, and the assignment’s due date in the heading on the top left of the first page. (Notice the date is written day, month, year without commas.)

- Center the essay title below the heading. Follow the rules on capitalization in Ch. 3.2. Do not increase font size, use bold, or underline.

- Begin the paper below the title. No extra spaces.

- Indent paragraphs 1” from the left margin.

Exercise 4

Give your essay a title, and then format it correctly.

Submit this draft to the instructor. Do not proceed to Ch. 7.4 until your draft has been approved.

Am I Finished Now?

The first draft of your essay is a complete piece of writing, but it is not finished. The best writing goes through multiple drafts before it is complete.

The final steps of the writing process–revising and editing–are crucial to the quality of the final document (and the grade you receive). During the next two steps, you will have the opportunity to make changes to your first draft.

Takeaways

- Most documents are built with three types of paragraphs: introductions, body paragraphs, and conclusions.

- The job of introductory paragraphs is to engage the reader and present the paper’s topic in a thesis.

- Body paragraphs develop the topic with supporting details.

- Concluding paragraphs wrap the paper up gracefully.

- Write the body paragraphs first, using your outline to guides the essay’s development. Each main idea becomes the topic sentence of a new paragraph.

- Write the introduction after the body paragraphs. Write the conclusion last.

- Titles should be clear and concise.

the preliminary or early version of a document

a short, subjective piece of writing that analyzes or interprets a topic

a brief statement of the essay's main point