7.1 Getting Started

Preview

This section of Ch. 7 will cover the following topics:

- using a writing process

- the purpose of prewriting

- types of prewriting

- choosing a good topic

Effective writing is simply good ideas, expressed well and arranged clearly.

But that can be more difficult than it sounds. Writing is not something one just sits down and does. You can write a text like that or a shopping list, but anything you are going to submit to a reader for evaluation–a job application, an essay, a report–should be planned and polished.

How does effective writing happen? Great writers use a writing process. Students who want to improve their writing learn that a writing process will help them reach that goal. A writing process also reduces stress and improves grades.

The Writing Process

The writing process outlined in this chapter is not difficult, but it takes several sessions. It has five steps:

- Prewrite: generate and begin developing ideas

- Organize: identify the document’s purpose, develop the thesis, generate the basic content, and choose an organizational pattern

- Draft: develop the points identified in the outline, add detail, examples, and commentary, then write an engaging introduction and a useful conclusion (after this step, the writer has a rough draft)

- Revise: review and reshape the draft; make moderate or major changes, adding or deleting sentences or even paragraphs, expanding important ideas, replacing a vague word with a more precise one, reorganizing points to improve quality and clarity

- Edit: make final changes to ensure adherence to standard writing conventions; fix errors in grammar and spelling, then apply formatting guidelines to ensure correctness (after this step, the writer has a first real draft)

Once these five steps have been completed, a careful writer will seek the advice of knowledgeable others before considering the project complete. In college, this usually takes the form of peer editing and tutors.

Then, a writer repeats Steps 4 and 5, re-revising and re-editing until she is satisfied. How long this takes depends on how long the writer has. In a timed exam, this step has to be done quickly. For a major paper, the writer should expect to do multiple revisions. The longer and more important the document is, the more time should be spent polishing. (For example, this textbook was revised and edited dozens of times with feedback from 4 editors!)

Notice the steps are similar to those in any creative project, not just writing. You’d follow the same steps to design a house or build a robot or paint a painting: come up with ideas (often vague at first), give them some structure, make a first attempt, figure out what needs improving, then refine and polish until you are satisfied.

Common Misconceptions

Some students have had good experiences with a writing process. Some have never even heard of a “writing process.” A few are hopeful. Others are doubtful that anything can help. Following are some common misconceptions students have about a writing process:

- “I do not have to waste time on prewriting if I understand the assignment.” Even if the task is straightforward and you feel ready to start writing, taking time to develop ideas before you write a draft gives you an opportunity to consider what you want to say before you jump in. It actually saves time overall.

- “It is important to complete a formal, numbered outline for every writing assignment.” For assignments such as lengthy research papers or books, a formal outline is helpful. For most college assignments, a scratch outline like the one recommended in this process is sufficient. The important thing is that you have a plan.

- “My draft will be better if I write it when I am feeling inspired.” By all means, take advantage of moments of inspiration. But understand that “inspired” work is often disorganized, incomplete, and unclear. Also, in college you often have to write when you are not in the mood.

- “My instructor will tell me everything I need to revise.” It is your job, not your instructor’s, to transform a rough draft into a final, polished piece of writing.

- “I am a good writer, so I do not need to revise or edit.” Revising and editing make poor writers into good writers, and good writers into great writers. Shakespeare revised his work. So did Jane Austen and George Orwell. Here is what Ernest Hemingway said when asked about revision:

Interviewer: “How much rewriting do you do?”

Hemingway: “It depends. I rewrote the ending of Farewell to Arms, the last page of it, 39 times before I was satisfied.”

Interviewer: “Was there some technical problem there? What was it that stumped you?”

Hemingway: “Getting the words right.”

—The Paris Review Interview, 1956

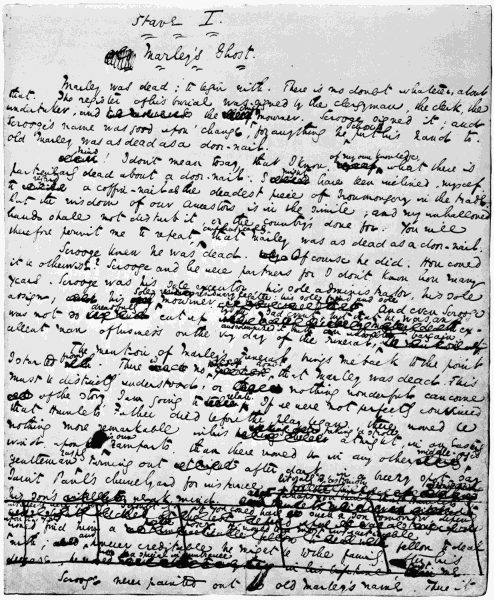

Graphics

Here is an example of one famous writer’s revisions. This is the first page of Charles Dickens’ hand-written manuscript of his classic novel A Christmas Carol. If Dickens had to revise and edit, you probably need to do so as well…

For examples of edits by other famous authors, check out this article:

For examples of edits by other famous authors, check out this article:

https://www.buzzfeed.com/alanamohamed/13-drafts-from-famous-authors-that-only-writers-can

So let’s get started.

Step 1: Prewriting

If you think a blank sheet of paper or a blinking cursor on a blank computer screen is scary, you are not alone. Beginning to write can be intimidating. However, any big project can be accomplished if you take it a step at a time.

Prewriting is the first stage of this writing process. Prewriting can help you get started if you don’t know where to begin. It also can help you narrow a topic that is too broad, help you explore what you know about your chosen topic, and find interesting examples and details to use in your paper. Prewriting is just brainstorming in writing.

We get our ideas from many places: what we read, what we hear, what we see and experience, our imagination. Prewriting helps us turn all of that information into words on a page. Prewriting is a way to think about what you think, to break through mental blocks, to get ideas out of your head and down on paper so you have something with which to work.

There are a few, very simple rules for prewriting:

- Use pencil and paper or a computer, whichever allows you to write more quickly.

- Write your topic at the top of the page to remind yourself to stick to it. If you wander off, just look at your topic and wander back.

- Don’t worry about spelling, punctuation, repetition, or exact wording. Your goal is to simply get as much information on the page as you can.

- Write for 10 minutes. More is unnecessary; less is not enough time to find unexpected ideas. Don’t stop and re-start. Keep pushing your brain to come up with one more idea and one more idea. That is when you find interesting and even surprising stuff.

Types of prewriting explained below include Freewriting, Questioning, Listing, and Clustering. Try them all, then use the technique that works best for your thinking process or for the specific assignment.

Freewriting

Freewriting is when you jot down thoughts that come to mind in rough sentences or phrases. Try not to doubt or question your ideas. Write freely. Don’t be self-conscious; nobody is going to grade this. Once you start writing without limitations, you may find you have more to say than you thought.

Here is an example of Freewriting on the topic of “the media.” Notice the writer isn’t worrying about grammar, fragments, or even staying on topic. She is just writing down everything that comes to mind about her topic.

Listing

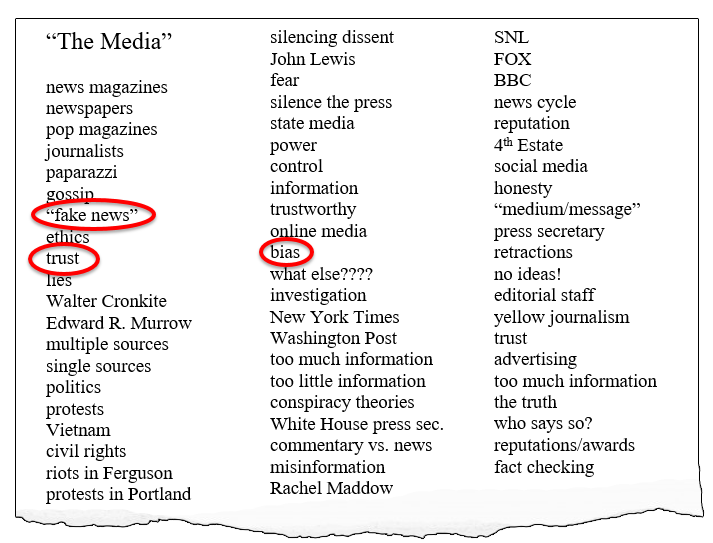

Listing is like Freewriting, but instead of writing across the page, you go from top to bottom, listing topics or details, one after another, without trying to sort or organize.

Here is an example of Listing on the topic of “the media.” Notice the ideas bounce from one to another, then off in a different direction. The point is to get as many ideas on the page as possible.

Questioning

Who? What? When? Where? Why? How?

In everyday situations, we pose these questions to get information. Who will be my partner for the project? What do I need to get at the grocery store? Why is my car making that noise? In prewriting, answering these kind of questions can help you recall ideas you already have and generate new thoughts about a topic.

To do Questioning, write the words “who, what, when, where, why, how” down the left-hand side of a sheet of paper, leaving space between the words. Then, in the blank space, answer the questions as they relate to your topic in as many ways as you can. Jump down to answer a question, then jump back up to answer a different one. Fill up the page.

Here is an example of Questioning on the topic of “the media”:

| Questions | Responses |

|---|---|

| Who? | Students, teachers, parents, politicians, employees–almost everyone uses media. Who creates media? Journalists, reporters, big companies, political groups. I guess anyone who wants to share information with others. |

| What? | Lots of things can be called “the media.” Television, radio, e-mail (?), newspapers, magazines, books. Is Dear Abby media? Are advertisements media? What about false advertising? |

| When? | Media has been around a long time, but seems a lot more important now. Is that because of computers? When did the news move from newspapers to TV to online? Is that good or bad? |

| Where? | The media is almost everywhere now. In homes, at work, in cars, on cell phones, even on watches and glasses! |

| Why? | This is a good question. Maybe we have mass media because we have the technology. But even in the 1700s we had newspapers, I think. I do think journalism is still important. How else can we know what is going on across the country or around the world? Are “the media” and “journalism” the same thing? Maybe not. One is information; the other is entertainment. |

| How? | Well, media is possible because of technology but I don’t know how they all work! How does a news article go from the event to me. Do I need to know? Probably. |

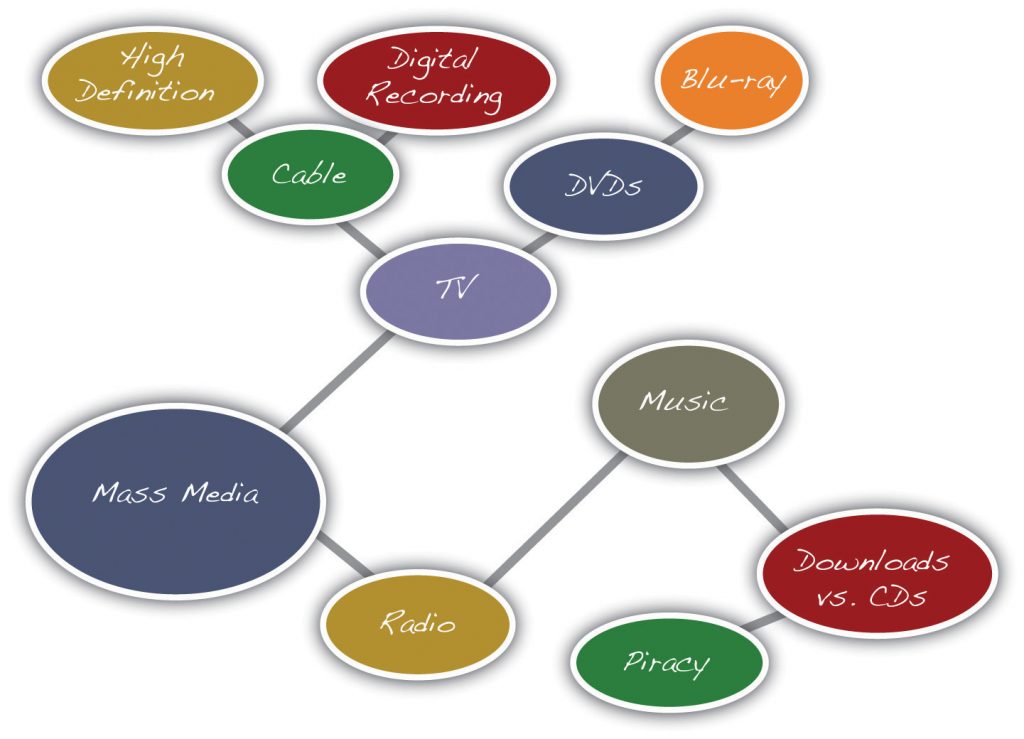

Clustering

Clustering allows you to visualize related ideas. Many writers like this method because it is easy to see how ideas connect.

To do Clustering, write your general topic in the center of a blank sheet of paper. Then brainstorm specific ideas around it and use lines or arrows to connect them. Add as many sub-ideas as you can think of. Write for 10 minutes; fill the page. A good Clustering exercise should fill the page with dozens of ideas.

Note: You can do this on a computer (like the example below) but it’s better on paper. On a computer, you spend too much time making little circles and choosing colors. On paper, you spend the time coming up with more ideas. The example below is just a start; each bubble needs to be developed further.

Exercise 1

You will do two prewrites for your essay.

First:

Do a first prewrite on the assigned topic. Your goal is to explore a broad topic to narrow it and make it your own. Use one of the prewriting styles explained above. You should end up with at least two pages full of words and ideas.

After you finish, read over what you wrote. Identify one or two narrow topics that might make a good essay. If you did not find a good topic, do another prewrite using a different style. Do not move on to the next task until you have a good topic for your essay.

Then:

Take that narrowed topic and do a second prewrite on it, using a different style of prewriting. The goal of this second prewrite is to generate lots of details about the topic to use in your essay. Again, you should produce at least two more pages full of words.

If you succeeded with these prewrites, you should have a good topic, one that interests you and is narrow enough to cover thoroughly in a short paper. You should also have lots of details to help you explain your point. Keep doing prewrites until you reach that goal.

Write your topic at the end of the document and submit it to the instructor for approval before moving on to the next step.

The goal of prewriting is to get information out of your head and onto a piece of paper where you can work with it. With a few ideas on paper, writers are often more comfortable continuing to write.

Choosing a Topic

Before you decide firmly on your topic, put it through a simple test. Answer these questions:

- Am I interested in this topic? Would my audience be interested?

- Do I have prior knowledge of or experience with my topic, or do I have the time to learn more about it?

- Is this topic narrow enough to cover thoroughly, but large enough to provide me with ideas to explore?

- Does it meet the assignment requirements?

When you can answer “yes” to all those questions, you are ready for Step 2 of the writing process.

Takeaways

- A writing process helps students complete any writing assignment more successfully.

- The process includes five steps. Allow sufficient time to complete each step before moving on to the next one.

- Prewriting is the first step. Prewriting is the transfer of ideas from abstract thoughts and feelings into words, phrases, and sentences on paper.

- Types of prewriting include Freewriting, Listing, Questioning, and Clustering.