6 Pregnancy and Fetal Development

Chapter Objectives

- Identify maternal and fetal changes that occur during each prenatal trimester

- Discuss possible dysfunction or complications that can occur during each trimester of pregnancy

- Describe a typical birth process along with at least four variations that could occur

- Describe the pros and cons associated with homebirth and hospital birth

- Discuss possible causes and symptoms of miscarriage and stillbirth

Pregnancy and Birthing Options

“Making the decision to have a baby (or adopt a child) is momentous. It is to decide forever to have your heart go walking around outside your body.” ~ Elizabeth Stone

“That she bear children is not a woman’s significance. But that she bear herself, that is her supreme and risky fate.” ~ D.H. Lawrence

To Have or Not to Have Children

One of the bigger choices we make as humans is the choice to have and raise children or to not have children. Sometimes it is not a choice at all but the result of circumstances given to us. Why might a person choose to have kids and what would the arguments be for choosing to remain childless? What circumstances might cause someone who so badly wants a child to be without? How might someone deal with an unexpected pregnancy when having a child was not part of the plan?

Video: I Don’t Want to Have Children, Stop Telling Me I Will Change My Mind.

Video: The Case for Having Kids.

Pregnancy

A missed period is often the first clue that a woman might be pregnant though she might suspect pregnancy even sooner. Symptoms such as headache, fatigue, and breast tenderness, can occur even before a missed period. The wait to know can be emotional. These days, many women first use home pregnancy tests (HPT) to learn they are pregnant.

All pregnancy tests work by detecting Human Chorionic Gonadotropic (hCG) in the urine or blood only present a woman is pregnant. hCG is made when a fertilized egg implants in the uterus and rapidly builds up in your body during early pregnancy.

Unplanned Pregnancy

In the event of an unplanned pregnancy many thoughts may come to mind. Will your partner welcome the news? Can you afford to care for the baby? Will choices such as past drug use addiction affect the health of the unborn baby? Will having a baby keep me from finishing school or pursuing a career?

First steps to take when a person fins out they are pregnant:

- Start taking care of yourself right away. Take 400 to 800 micrograms (400 to 800 mcg or 0.4 to 0.8 mg) folic acid every. Stop alcohol, tobacco, and drug use.

- Make a doctor’s visit to confirm your pregnancy. Discuss your health and issues that could affect your pregnancy. Ask for help quitting smoking. Find out what you can do to take care of yourself and your unborn baby.

- Ask your doctor to recommend a counselor who you can talk to about your situation.

- Seek support in someone you trust and respect.

Trying to Get Pregnant

Some women want children but either cannot conceive or miscarry multiple times. Many couples face infertility when trying to start or grow a family. About one-third of the time, it is a female problem. In another one-third of cases, it is the man with the fertility problem. For the remaining one-third, both partners have fertility challenges or no cause is found.

Causes of infertility

Age – Women generally have some decrease in fertility starting in their early 30s. As a woman ages, normal changes that occur in her ovaries and eggs make it harder to become pregnant. Even though menstrual cycles continue to be regular in a woman’s 30s and 40s, the eggs that ovulate each month are of poorer quality than those from her 20s. As a woman nears menopause, the ovaries may not release an egg each month, which also can make it harder to get pregnant.

Health problems – Some women have diseases or conditions that affect their hormone levels, which can cause infertility. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) rarely or never ovulate. Failure to ovulate is the most common cause of infertility in women.

Common problems with a woman’s reproductive organs, like uterine fibroids, endometriosis, and pelvic inflammatory disease can worsen with age and also affect fertility. These conditions might cause a blockage in the fallopian tubes to be blocked preventing the egg from getting to the uterus.

Lifestyle factors – Certain lifestyle factors also can have a negative effect on a woman’s fertility. Examples include smoking, alcohol use, weighing much more or much less than an ideal body weight, a lot of strenuous exercise, and having an eating disorder. Stress also can affect fertility.

When to see your doctor

You should talk to your doctor about your fertility if:

* You are younger than 35 and have not been able to conceive after one year of frequent sex without birth control.

- You are age 35 or older and have not been able to conceive after six months of frequent sex without birth control.

- You believe you or your partner might have fertility problems in the future (even before you begin trying to get pregnant).

- You or your partner has a problem with sexual function or libido.

If you are having fertility issues, your doctor can refer you to a fertility specialist. About 9 in 10 cases of infertility are treated with drugs or surgery. Don’t delay seeing your doctor as age also affects the success rates of these treatments. For some couples, adoption or foster care offers a way to share their love with a child and build a family.

Increasing Likelihood of Pregnancy

Being aware of the menstrual cycle and the changes in the body that happen during mensuration can help a woman know when she is likely to get pregnant.

There are ways you can keep track of your fertile times in the menstrual cycle. They are:

- Basal body temperature method – Basal body temperature is your temperature at rest as soon as you awake in the morning. A woman’s basal body temperature rises slightly with ovulation. So by recording this temperature daily for several months, a woman will be able to predict the most fertile days.

- Calendar method– This involves recording your menstrual cycle on a calendar for eight to 12 months. The first day of a period is Day 1. Circle Day 1 on the calendar and record down the total number of days a cycle it lasts each time. Days 12-14 of the cycle will be a woman’s most fertile days.

- Cervical mucus method (also known as the ovulation method) – This involves being aware of the changes in your cervical mucus throughout the month. The hormones that control the menstrual cycle also change the kind and amount of mucus before and during ovulation. The greatest amount of mucus appears just before ovulation.

Preconception Care: Why Preconception Health Matters

Preconception health is a woman’s health before she becomes pregnant. It means knowing how health conditions and risk factors could affect a woman or her unborn baby if she becomes pregnant. For example, some foods, habits, and medicines can harm a baby — even before conception. Some health problems, such as diabetes, also can affect pregnancy.

It is important for any person thinking about their health, but with half of all pregnancies unplanned it is especially important to consider behaviors that may affect the health of a baby. Unplanned pregnancies are at greater risk of preterm birth and low birth weight babies. Despite important advances in medicine and prenatal care, about 1 in 8 babies is born too early. Researchers are trying to find out why and how to prevent preterm birth. But experts agree that women need to be healthy before becoming pregnant. By taking action on health issues and risks before pregnancy, a person can prevent problems that might affect mom or baby later.

Improving Preconception Health

Ideally, couple should prepare for pregnancy at least three months before getting pregnant. Some actions, such as quitting smoking, reaching a healthy weight, or adjusting medicines may need to start even earlier.

The five most important things a woman can do for preconception health are:

- Take 400 to 800 micrograms (400 to 800 mcg or 0.4 to 0.8 mg) of folic acid every day if you are planning or capable of pregnancy to lower your risk of some birth defects of the brain and spine, including spina bifida.

- Stop smoking and drinking alcohol.

- If you have a medical condition, be sure it is under control. Some conditions that can affect pregnancy or be affected by it include asthma, diabetes, oral health, obesity, or

- Talk to your doctor about any over-the-counter and prescription medicines you are using. These include dietary or herbal supplements. Be sure your vaccinations are up to date.

- Avoid contact with toxic substances or materials that could cause infection at work and at home. Stay away from chemicals and cat or rodent feces.

Anatomical and Physiological Changes that Occur During Pregnancy

A full-term pregnancy lasts approximately 270 days (approximately 38.5 weeks) from conception to birth. Because it is easier to remember the first day of the last menstrual period (LMP) than to estimate the date of conception, obstetricians set the due date as 284 days (approximately 40.5 weeks) from the LMP. This assumes that conception occurred on day 14 of the woman’s cycle, which is usually a good approximation. The 40 weeks of an average pregnancy are usually discussed in terms of three trimesters, each approximately 13 weeks. We will express embryonic and fetal ages in terms of weeks from conception. The period of time required for full development of a fetus in utero is referred to as gestation (gestare = “to carry” or “to bear”).

A developing human is referred to as a zygote for the first 2 weeks after conception, an embryo during weeks 3–8, and a fetus from the ninth week of gestation until birth.

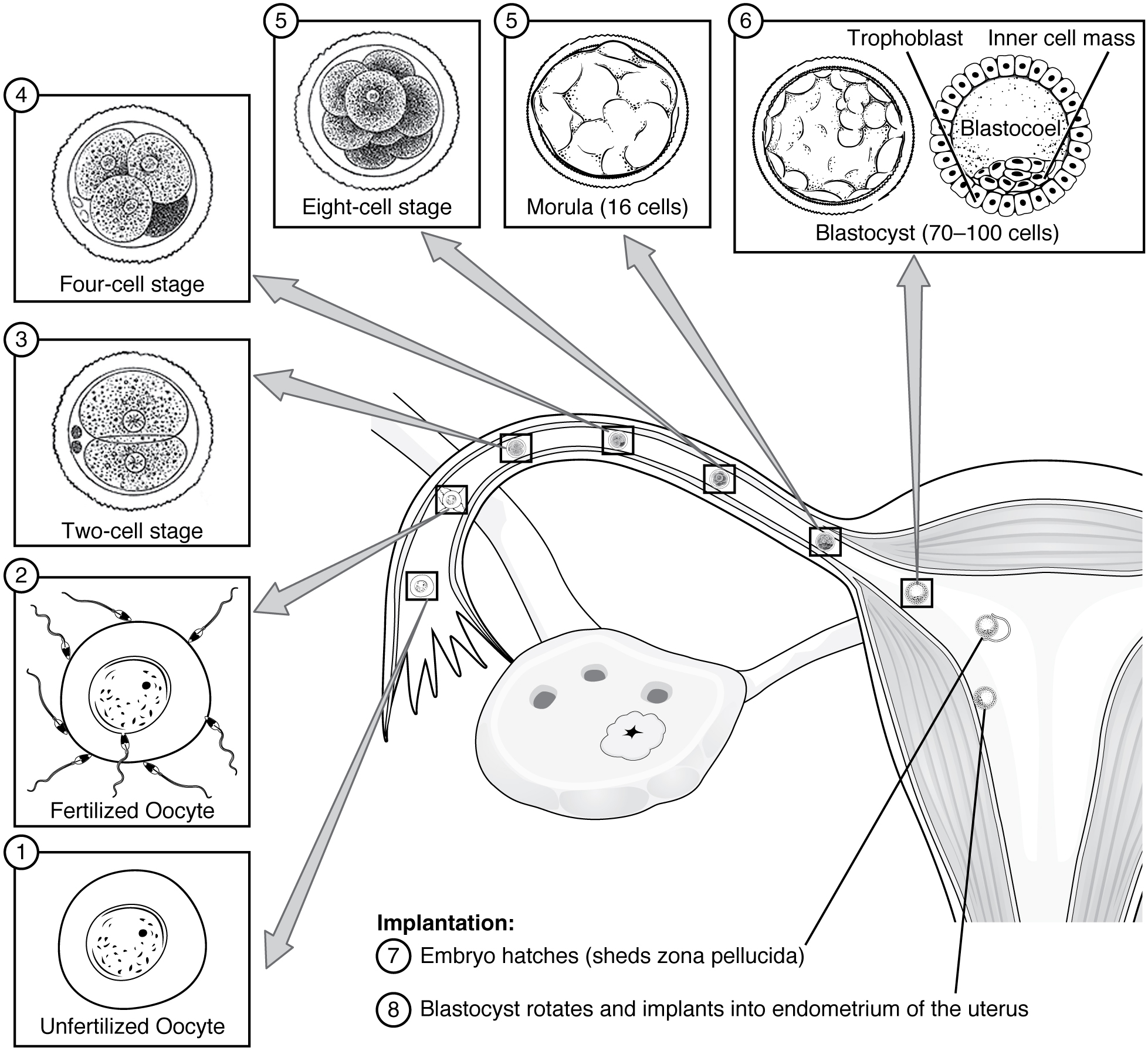

Implantation

Following fertilization, the zygote and its associated membranes, continue their travel through the fallopian tube toward the uterus. During its journey to the uterus, the zygote undergoes five or six rapid mitotic cell divisions. At the end of the first week, the blastocyst comes in contact with the uterine wall and adheres to it, embedding itself in the uterine lining (referred to as implantation). (Figure 2). Implantation can be accompanied by minor bleeding. The zygote typically implants in the fundus of the uterus or on the posterior wall. However, if the endometrium is not fully developed and ready to receive the zygote, the zygote and associated cells will detach and find a better spot. A significant percentage (50–75 percent) of zygotes fail to implant; when this occurs, the cell bundle is shed with the endometrium during menses. The high rate of implantation failure is one reason why successful pregnancy typically requires several ovulation cycles.

Just a few days after implantation, the mass of cells has secreted enough hCG (human growth hormone) for an at-home urine pregnancy test to give a positive result. However, in one to two percent of cases, the embryo implants either outside the uterus or in a region of uterus that can create complications for the pregnancy.

Dysfunction During Implantation

In the vast majority of ectopic pregnancies, the embryo does not complete its journey to the uterus and implants in the uterine tube, referred to as a tubal pregnancy. However, there are also ovarian ectopic pregnancies (in which the egg never left the ovary) and abdominal ectopic pregnancies (in which an egg was “lost” to the abdominal cavity during the transfer from ovary to uterine tube, or in which an embryo from a tubal pregnancy re-implanted in the abdomen).

Tubal pregnancies can be caused by scar tissue within the tube following a sexually transmitted bacterial infection. The scar tissue impedes the progress of the embryo into the uterus—in some cases “snagging” the embryo and, in other cases, blocking the tube completely. Approximately one half of tubal pregnancies resolve spontaneously. Implantation in a uterine tube causes bleeding, which appears to stimulate smooth muscle contractions and expulsion of the embryo. In the remaining cases, medical or surgical intervention is necessary.

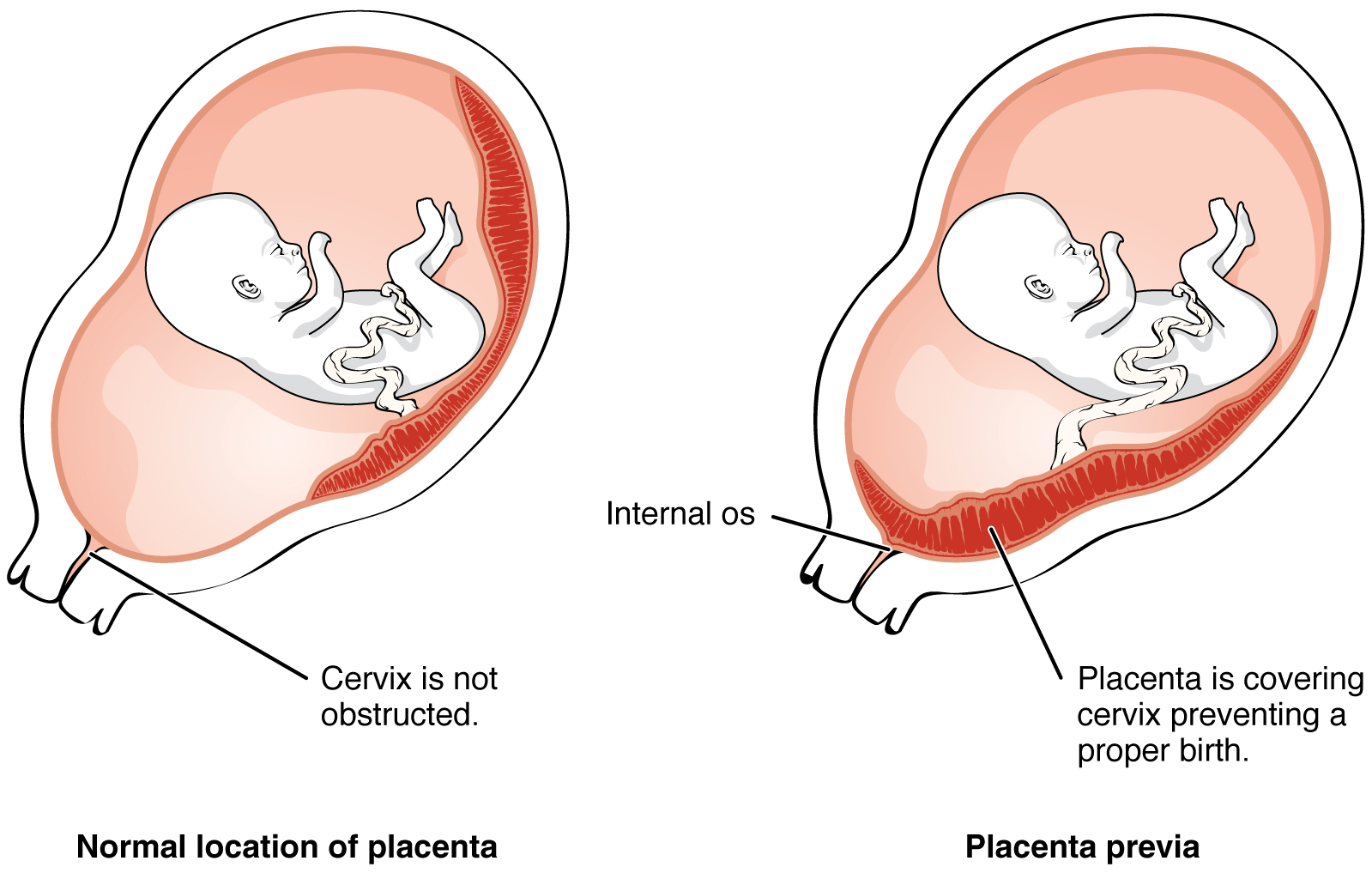

Even if the embryo has successfully found its way to the uterus, it does not always implant in an optimal location (the fundus or the posterior wall of the uterus). Placenta previa can result if an embryo implants close to the internal opening of the cervix. As the fetus grows, the placenta can partially or completely cover the opening of the cervix (Figure 4). Although it occurs in only 0.5 percent of pregnancies, placenta previa is the leading cause of antepartum hemorrhage (profuse vaginal bleeding after week 24 of pregnancy but prior to childbirth).

Development of the Placenta

During the first several weeks of development, the cells of the endometrium (uterus) nourish the embryo. During prenatal weeks 4–12, the developing placenta gradually takes over the role of feeding the embryo, and the endometrial cells are no longer needed. The mature placenta is composed of tissues derived from the embryo, as well as maternal tissues of the endometrium. The placenta connects to the embryo via the umbilical cord, which carries deoxygenated blood and wastes from the fetus through two umbilical arteries; nutrients and oxygen are carried from the mother to the fetus through the single umbilical vein.

Embryotic Development

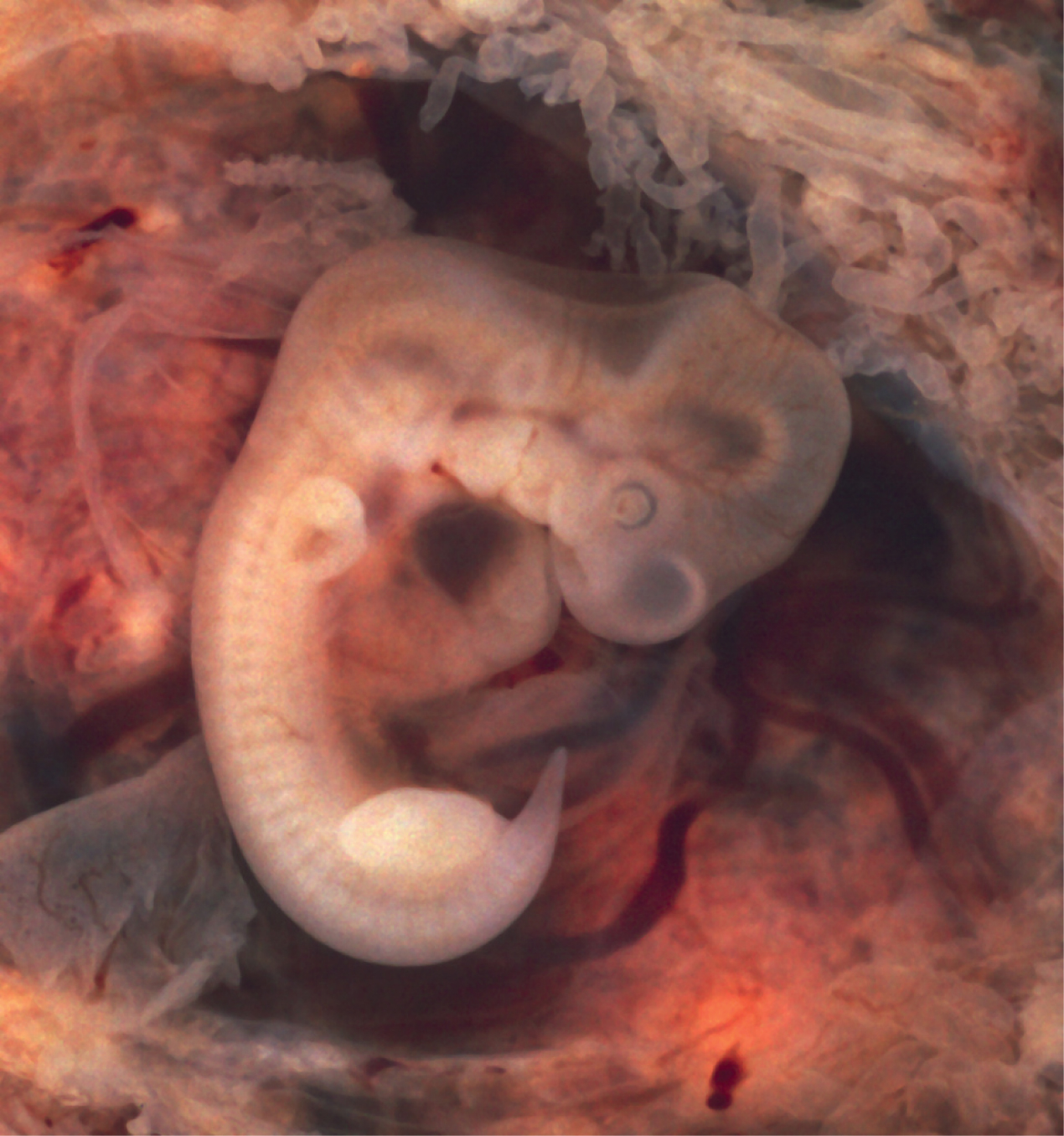

Within the first 8 weeks of gestation, a developing embryo establishes the rudimentary structures of all of its organs and tissues. The heart begins its development in the embryo as a tube-like structure, connected via capillaries. Cells of the primitive tube-shaped heart are capable of electrical conduction and contraction. The heart begins beating in the beginning of the fourth week, although it does not actually pump embryonic blood until a week later, when the oversized liver has begun producing red blood cells. (This is a temporary responsibility of the embryonic liver that the bone marrow will assume during fetal development.) During weeks 4–5, the eye pits form, limb buds become apparent, and the rudiments of the pulmonary system are formed.

During the sixth week, uncontrolled fetal limb movements begin to occur. The gastrointestinal system develops too rapidly for the embryonic abdomen to accommodate it, and the intestines temporarily loop into the umbilical cord. Paddle-shaped hands and feet develop fingers and toes. By week 7, the facial structure is more complex and includes nostrils, outer ears, and lenses (Figure 12). By the eighth week, the head is nearly as large as the rest of the embryo’s body, and all major brain structures are in place. The external genitalia are apparent, but at this point, male and female embryos are indistinguishable. Bone begins to replace cartilage in the embryonic skeleton through the process of ossification. By the end of the embryonic period, the embryo is approximately 3 cm (1.2 in) from crown to rump and weighs approximately 8 g (0.25 oz).

Sexual Differentiation

Sexual differentiation does not begin until the fetal period, during weeks 9–12. Embryonic males and females, though genetically distinguishable, are morphologically identical. Gonads that can develop into male or female sexual organs, are connected to a central cavity called the cloaca via Müllerian ducts (female)and Wolffian ducts (male).

During male fetal development, the gonads become the testes and associated epididymis. The Müllerian ducts degenerate. The Wolffian ducts become the vas deferens.

During female fetal development, the gonads develop into ovaries. The Wolffian ducts degenerate. The Müllerian ducts become the uterine tubes and uterus.

Fetal Development

During weeks 9–12 of fetal development, the brain continues to expand, the body elongates, and ossification of bones continues. Fetal movements are frequent during this period, but are jerky and not well-controlled. The bone marrow begins to take over the process of red blood cell production. The eyes are well-developed by this stage, but the eyelids are fused shut. The fingers and toes begin to develop nails. By the end of week 12, the fetus measures approximately 9 cm (3.5 in) from crown to rump.

Weeks 13–16 are marked by sensory organ development. The eyes move closer together; blinking motions begin, although the eyes remain sealed shut. The lips exhibit sucking motions. The scalp begins to grow hair.

During approximately weeks 16–20, as the fetus grows and limb movements become more powerful, the mother may begin to feel quickening, or fetal movements. However, space restrictions limit these movements and typically force the growing fetus into the “fetal position,” with the arms crossed and the legs bent at the knees. Oil glands coat the skin with a waxy, protective substance called vernix that protects and moisturizes the skin and may provide lubrication during childbirth. A silky hair called lanugo also covers the skin during weeks 17–20, but it is shed as the fetus continues to grow. Extremely premature infants sometimes exhibit residual lanugo.

Developmental weeks 21–30 are characterized by rapid weight gain, which is important for maintaining a stable body temperature after birth. During this period, the fetus grows eyelashes. The eyelids are no longer fused and can be opened and closed. The lungs begin producing surfactant, a substance that reduces surface tension in the lungs and assists proper lung expansion after birth. In male fetuses, the testes descend into the scrotum near the end of this period. The fetus at 30 weeks measures 28 cm (11 in) from crown to rump and exhibits the approximate body proportions of a full-term newborn, but still is much leaner.

The fetus continues to lay down fat under the skin from week 31 until birth which causes and the skin transitions from red and wrinkled to soft and pink. Lanugo is shed, and the nails grow to the tips of the fingers and toes. Immediately before birth, the average crown-to-rump length is 35.5–40.5 cm (14–16 in), and the fetus weighs approximately 2.5–4 kg (5.5–8.8 lbs). Once born, the newborn is no longer confined to the fetal position, so subsequent measurements are made from head-to-toe instead of from crown-to-rump. At birth, the average length is approximately 51 cm (20 in).

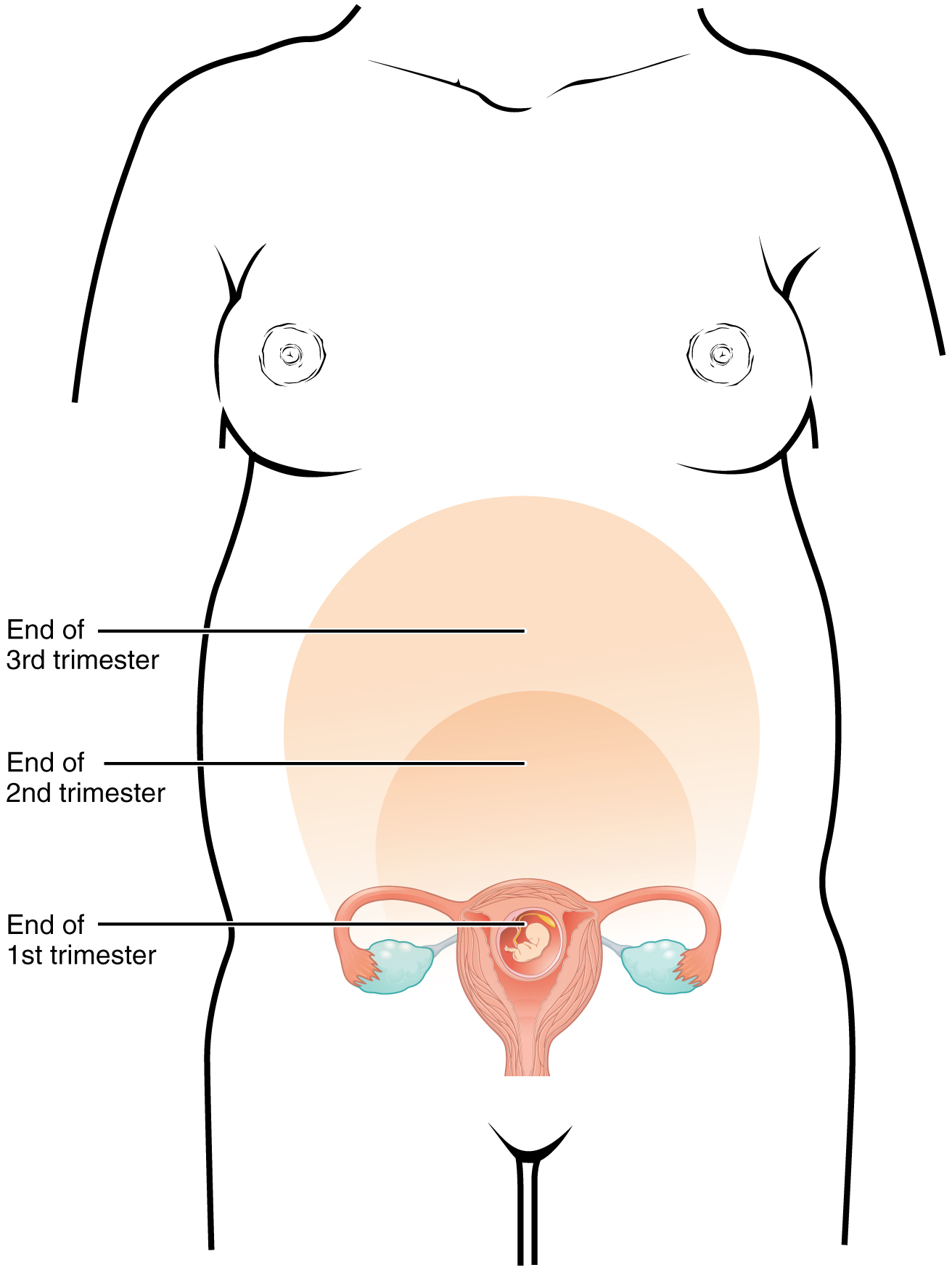

Maternal Changes

The 40 weeks of an average pregnancy are usually discussed in terms of three trimesters, each approximately 13 weeks. During the second and third trimesters, the pre-pregnancy uterus—about the size of a fist—grows dramatically to contain the fetus, causing a number of anatomical changes in the mother.

Effects of Hormones

Virtually all of the effects of pregnancy can be attributed in some way to the influence of hormones—particularly estrogens, progesterone, and hCG. Relaxin, another hormone secreted by the placenta, helps prepare the mother’s body for childbirth. It increases the elasticity of the pubic joint and pelvic ligaments, making room for the growing fetus and allowing expansion of the pelvic outlet for childbirth. Relaxin also helps dilate the cervix during labor.

Weight Gain

The second and third trimesters of pregnancy are associated with dramatic changes in maternal anatomy and physiology. The most obvious anatomical sign of pregnancy is the dramatic enlargement of the abdominal region, coupled with maternal weight gain. This weight results from the growing fetus as well as the enlarged uterus, amniotic fluid, and placenta. Additional breast tissue and dramatically increased blood volume also contribute to weight gain (Table 2). Surprisingly, fat storage accounts for only approximately 2.3 kg (5 lbs) in a normal pregnancy and serves as a reserve for the increased metabolic demand of breastfeeding.

During the first trimester, the mother does not need to consume additional calories to maintain a healthy pregnancy. However, a weight gain of approximately 0.45 kg (1 lb) per month is common. During the second and third trimesters, the mother’s appetite increases, but it is only necessary for her to consume an additional 300 calories per day to support the growing fetus. Most women gain approximately 0.45 kg (1 lb) per week.

| Contributors to Weight Gain During Pregnancy (Table 2) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Component | Weight (kg) | Weight (lb) |

| Fetus | 3.2–3.6 | 7–8 |

| Placenta and fetal membranes | 0.9–1.8 | 2–4 |

| Amniotic fluid | 0.9–1.4 | 2–3 |

| Breast tissue | 0.9–1.4 | 2–3 |

| Blood | 1.4 | 4 |

| Fat | 0.9–4.1 | 3–9 |

| Uterus | 0.9–2.3 | 2–5 |

| Total | 10–16.3 | 22–36 |

Changes in Organ Systems During Pregnancy

As the woman’s body adapts to pregnancy, characteristic physiologic changes occur. These changes can sometimes prompt symptoms often referred to collectively as the common discomforts of pregnancy.

Digestive and Urinary System Changes

Nausea and vomiting, sometimes triggered by an increased sensitivity to odors, are common during the first few weeks to months of pregnancy. This phenomenon is often referred to as “morning sickness,” although the nausea may persist all day. The source of pregnancy nausea is thought to be the increased circulation of pregnancy-related hormones. By about week 12 of pregnancy, nausea typically subsides.

A common gastrointestinal complaint during the later stages of pregnancy is gastric reflux, or heartburn, which results from the upward, constrictive pressure of the growing uterus on the stomach.

The downward pressure of the uterus also compresses the urinary bladder, leading to frequent urination. In addition, the maternal urinary system processes both maternal and fetal wastes, further increasing the total volume of urine.

Circulatory System Changes

Blood volume increases substantially during pregnancy, so that by childbirth, it exceeds its preconception volume by 30 percent, or approximately 1–2 liters. The greater blood volume helps to manage the demands of fetal nourishment and fetal waste removal. In conjunction with increased blood volume, the pulse and blood pressure also rise moderately during pregnancy. As the fetus grows, the uterus compresses underlying pelvic blood vessels, hampering venous return from the legs and pelvic region. As a result, many pregnant women develop varicose veins or hemorrhoids.

Respiratory System Changes

During the second half of pregnancy, the volume of gas inhaled or exhaled by the lungs per minute increases by 50 percent to compensate for the oxygen demands of the fetus and the increased maternal metabolic rate. The growing uterus exerts upward pressure on the diaphragm, decreasing the volume of each inspiration and potentially causing shortness of breath. During the last several weeks of pregnancy, the pelvis becomes more elastic, and the fetus descends lower in a process called lightening. This typically alleviates shortness of breath.

Skin Changes

The skin stretches extensively to accommodate the growing uterus, breast tissue, and fat deposits on the thighs and hips. Torn connective tissue cause stretch marks on the abdomen, which appear as red or purple marks during pregnancy that fade to a silvery white color in the months after childbirth.

An increase in melanin-stimulating hormone, in conjunction with estrogens, darkens the areolae and creates a line of pigment from the umbilicus to the pubis called the linea nigra (Figure 2). Melanin production during pregnancy may also darken or discolor skin on the face to create a chloasma, or “mask of pregnancy.”

Check for Understanding

- What are some reasons a person may decide to have or not have children?

- How can a person increase the likelihood of becoming pregnant or contributing to a pregnancy?

- What are some common causes of infertility?

- What are some important factors to consider in preconception health?

- What are the various stages of development by trimester for embryo/fetus?

- What are some maternal changes during pregnancy?