3 Nutrition and Fitness

Chapter Objectives

- List the macronutrients and micronutrients essential to body function and describe specific functions in the body

- Discuss nutrients deficiencies common in women and how these deficiency may impact future health

- List types of fitness training important to maintaining physical wellness

- Calculate personal caloric balance using BMR and AMR

Exercise is a celebration for what your body can do, not a punishment for what you ate. ~ Sachin Pinate

Nutrition and Healthy Eating

After learning about anatomical structures in chapter 2 we continue with methods and behaviors that keep body systems healthy and lower risk of disease or dysfunction. The foods we eat affect all dimensions of health and wellness. Many of the health issues associated with poor eating habits are a result of an energy imbalance or lack of nutrients. Most Americans are obtaining more energy from food than they actually need to function in their daily lives and fewer vitamins and minerals.

Nutrients

Ideally, when we consume and obtain energy from our food, we will primarily eat nutrient dense foods. A nutrient is a compound that provides a needed function in the body. The six Essential Nutrients are the nutrients that our bodies need in order to survive. They can be broken into two categories: macronutrients and micronutrients.

Macronutrients are nutrients needed in larger amounts. There are four macronutrients which include:

- Carbohydrates: 4 calories per gram

- Fats (lipids): 9 calories per gram

- Protein: 4 calories per gram

- Water: contains 0 calories

As can be seen, carbohydrates, protein, and fats provide energy. However, there is another energy source in the diet that is not a nutrient- alcohol. Alcohol has 7 calories per gram.

Micronutrients are nutrients needed in smaller amounts, but they are still considered essential. There are two groups of micronutrients which are:

- Vitamins

- Minerals

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates provide energy for the body as well as fiber for digestive health and blood sugar regulation. Many natural carbohydrates such as fruits, vegetables and whole grains provide essential vitamins and minerals.

Although grains and starchy foods are most often associated with carbohydrates, almost all foods do contain some carbohydrates. Some dietary examples of carbohydrate rich foods are whole-wheat bread, oatmeal, rice, sugary snacks/drinks, and pasta. There are many different types of carbohydrates, but the three main types are: simple, complex, and alternative sugar sweeteners.

Simple Carbohydrates

Simple carbohydrates provide quick energy for the body with a spike in blood sugar. If used before exercise or activity this energy can be beneficial and if taken in as fruit and veggies, also very nutritious. However, empty simple sugars, such as candy, cause a rise and then drop in blood sugar that may leave a person hungry a short time later without providing the body necessary vitamins and minerals for growth and maintenance.

Food manufacturers are always searching for cheaper ways to produce food. One method that has been popular is the use of high-fructose corn syrup as an alternative to sucrose (table sugar). High-fructose corn syrup contains 55% fructose which is similar to sucrose. Nevertheless, because an increase in high-fructose corn syrup consumption has coincided with the increase of obesity in the US, there is a lot of controversy surrounding its use. In reading labels, one will usually see high-fructose corn syrup plus other sugars listed which could be adding to the obesity epidemic.

High-Fructose Corn Syrup

Food manufacturers are always searching for cheaper ways to produce their products. One extremely popular method for reducing costs is the use of high-fructose corn syrup as an alternative to sucrose. High-fructose corn syrup is approximately 50% glucose and 50% fructose, which is the same as sucrose. Nevertheless, because increased consumption of high-fructose corn syrup has coincided with increased obesity in the United States, a lot of controversy surrounds its use.

The New York Times article linked below discusses the growing popularity of sugar compared to high fructose corn syrup: “Sugar is Back on Food Labels, This Time as a Selling Point”

Complex Carbohydrates

Complex Carbohydrates contain many sugar molecules while simple carbohydrates contain only one or two sugars. Complex Carbohydrates are called polysaccharides. Poly means “many,” and thus polysaccharides are made of more than 10 sugar molecules. There are two classes of food based polysaccharides: starch and fiber. Starch is a main source of fuel for the cells. After cooking, starch becomes digestible for humans. Raw starch may resist digestion. Examples of starch foods are corn, potatoes, rice, beans, pasta, and grains. Fiber is indigestible matter that survives digestion in the small intestine and stays intact in the large intestine. It is divided into two categories: soluble and insoluble. Soluble means it can be dissolved in water, and insoluble means it does not dissolve in water.

- Soluble fibers are fermentable fibers. It is believed that these fibers decrease blood cholesterol and sugar levels thus lowering the risk of heart disease and diabetes II.

- Insoluble fibers are non-fermentable, and it is believed that this type of fiber decreases the risk of constipation and colon cancer because it increases stool bulk and reduces transit time. This reduced transit time means shorter exposure to consumed carcinogens in the intestine which may lower cancer risk.

The goal for a day’s fiber intake is 25-40 grams depending on one’s caloric intake. Suggestions would be to buy high fiber foods. Read the Nutrition Facts’ label for how much fiber is in the product for one serving. Drink lots of fluids when eating fiber. Try to eat a minimum of five plant foods for fiber each day.

Carbohydrates have become, surprisingly, quite controversial. However, it is important to understand that carbohydrates are a diverse group of compounds that have a multitude of effects on bodily functions. Thus, trying to make blanket statements about carbohydrates is not a good idea.

Fats (Lipids)

- Triglycerides

- Oils

- Cholesterol

Fats (lipids) are the most concentrated source of energy at 9 calories per gram. Fats provide long term stored energy (in the from of triglycerides), insulation, cushion, and help the body absorb fat-soluble vitamins. Depending on the fatty acid structure a lipid may be monounsaturated, polyunsaturated, or saturated.

Triglycerides

Triglycerides are molecules made of glycerol and fatty acids. They are the major form of energy storage in animals.

Triglycerides perform the following functions in our bodies:

- Provide energy

- Primary form of energy storage in the body

- Insulate and protect

- Aid in the absorption and transport of fat-soluble vitamins.

Structures of Fatty Acids

Fatty acids are components of triglycerides. They are like the brick in a brick wall. Each individual brick is needed to make the overall wall. There are two basic types of fatty acids:

- saturated fatty acid

- unsaturated fatty acid

These molecules differ in structure and food sources. Saturated fats are typically found in animal products such as poultry, meat and dairy and are solid at room temperature. Unsaturated fats are typically found in plants and vegetable oils and are liquid at room temperature. There are also monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), which have a healthy affect on cholesterol levels.

There are two essential fatty acids, which are:

- linoleic acid (omega-6)

- alpha-linolenic (omega-3)

These fatty acids are essential because the body cannot synthesize them. The essential fatty acids are critical to human health as they play important roles in every system of the body. Good food sources of omega-6 include whole grains, fresh fruits and veggies, fish, olive oil, and garlic. Good food sources of omega-3 include flax seed, egg yolk, and chia seeds.

Trans-fatty acids

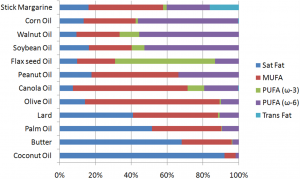

Trans-fatty acids – like Crisco- are hydrogenated vegetable oils. In an artificial chemical process hydrogen is added to natural vegetable oils to make them more solid at room temperature, and more heat resistant for cooking, thus, hydrogenated oils are more resistant to heat degradation. The body doesn’t have an efficient process for using trans-fats, so they get stored for the long term. The figure below shows the fatty acid composition of certain oils and oil-based foods. As can be seen, most foods contain a mixture of fatty acids.

Figure 1. Different Types of Fat

Cholesterol

Cholesterol is a type of lipid found in the blood. It has many functions and is a structural part of all body cells, including brain and nerve tissue. Cholesterol is needed to form hormones, bile, and vitamin D. Many foods contain cholesterol, but primarily it is found in foods of animal origin. Some meats are higher in cholesterol than others.

The body needs cholesterol, but it produces all of the cholesterol that it needs. It is almost impossible to avoid consuming outside sources of cholesterol, but it is possible and advisable to limit cholesterol intake by avoiding foods high in cholesterol. Elevated levels of LDL (“bad cholesterol”) in the blood can increase the risk of artery and heart disease.

The human body contains two types of cholesterol: low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL).

LDL: The “Bad” Cholesterol

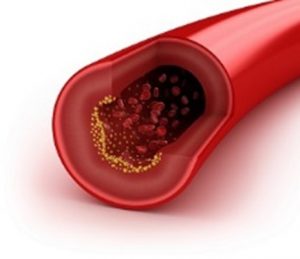

LDL is cholesterol that usually enters the human body through consuming food that contains cholesterol. LDL is considered the “bad cholesterol” because it bonds with triglycerides and stores it within the tissues. This is the leading cause of plaque in the arteries and can lead to restricted blood flow and possible cardiac arrest. This process takes place over several years with continuous eating of saturated fats, smoking, diabetes, and high blood pressure.

Figure 2. Blood flow restricted by the buildup of LDL cholesterol

Cholesterol plaque in the artery

HDL: The “Good” Cholesterol

HDL is produced when a person exercises, and it is considered the “good cholesterol.” HDL also bonds with triglycerides, but it is then processed by the body, added to feces, and expelled through the colon. In other words, HDL helps the body to process excess triglycerides thus managing the amount of excess fat in the overall system. The best way to increase HDL in the body is to exercise regularly.

A Lipid Panel is a series of tests that measures the amount of cholesterol in the blood. A small sample of blood is drawn from the patient for this test. One number is for “total cholesterol.” This number will show the total fats in the blood. The HDL will show the good fats; LDL will show the bad fats; Triglycerides will show good or bad fats depending on the number above or below 150.

Adult Blood Cholesterol and Triglyceride Target Numbers:

- Total Cholesterol < 200 mg/dl

- Total HDL > 35

- Total LDL < 100

- Total Triglycerides < 150

Proteins

Proteins are another major macronutrient. They are similar to carbohydrates in that they are made up of small repeating units, but instead of sugars, proteins are made up of amino acids. Protein makes up approximately 20 percent of the human body and is present in every single cell. The word protein is a Greek word, meaning “of utmost importance.” Proteins are called the workhorses of life as they provide the body with structure and perform a vast array of functions. You can stand, walk, run, skate, swim, and more because of your protein-rich muscles. Protein is necessary for proper immune system function, digestion, and hair and nail growth, and is involved in numerous other body functions. In fact, it is estimated that more than one hundred thousand different proteins exist within the human body.

What Is Protein?

Proteins, simply put, are macromolecules composed of amino acids. Amino acids are commonly called protein’s building blocks.

The functions of proteins are very diverse because there are 20 distinct amino acids that form long chains. For example, proteins can function as enzymes or hormones. Enzymes, one type of protein, are produced by living cells and are catalysts in biochemical reactions (like digestion). Enzymes can function to break molecular bonds, to rearrange bonds, or to form new bonds. An example of an enzyme is salivary amylase which breaks down amylose, a component of starch.

Amino Acids Function

Amino acids are combined in order to form all of the protein the human body needs. In fact, the body makes proteins itself, but it needs amino acids from food to construct proteins that the body uses. Antibodies, enzymes, muscle proteins, as well as proteins in the skin are all made up of amino acids, some that the body produces and some that must be consumed. Amino acids that the body produces are called non-essential amino acids. There are eleven non-essential amino acids: alanine, arginine, asparagine, aspartate, cysteine, glutamic acid, glutamine, glycine, proline, serine and tyrosine. In Nutrition, the term essential is used to name nutrients that the body doesn’t produce itself; essential nutrients including essential amino acids must be consumed. There are nine essential amino acids: histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan and valine.

Complete and Incomplete Proteins

As a way of simplifying protein, sources are described as either complete or incomplete. Complete proteins – such as eggs, tuna fish, peanut butter, almonds – contain most if not all of the essential amino acids. Incomplete proteins – such as spinach, beans, wheat germ – contain just a few of the essential amino acids.

Most plant-based proteins are categorized as incomplete proteins, but vegetarians should not be concerned about protein intake because a person can consume all of the essential amino acids by combining food sources. For example a person can eat beans and quinoa with a spinach salad and consume the essential amino acids.

Water

Water is made up of hydrogen and oxygen (H2O) and doesn’t provide energy for the body (calories). Humans are approximately 65% water! The body needs water to regulate temperature, moisten tissues in the mouth, eyes, and nose, lubricate joints, protect organs, prevent constipation, reduce the burden on kidneys and liver by helping to flush out waste, and to dissolve nutrients as part of the digestive process.

Although a person can survive for several weeks without food, the body cannot survive longer than a few days without fluids. A loss of water equivalent to:

- 1% of body weight is enough to cause thirst and to impact the ability to concentrate

- 4% loss of hydration results in dizziness and reduced muscle power

- 6% loss of fluids causes the heart to race and sweating ceases

- 7% loss of hydration results in collapse and subsequent death if fluids are not replaced

Water Intake

In a normal diet, fluid is gained via food as well as in drinks. Water, along with some herbal teas and low sugar juices hydrate the body. However, alcoholic, high sugar, and caffeinated drinks may not contribute to body fluids as alcohol, sugar and caffeine are diuretics, substances that increases the output of urine by the body.

Fluid loss occurs in various ways throughout the body with urination being the primary method. Perspiration (sweating), and respiration (breathing) also removes fluid from the body. Water intake and water loss should be balanced in order to prevent dehydration and to maintain a healthy body. The recommended daily intake is 10-13 cups of fluid from food and drink for adult males and 7-9 cups of fluid for adult females or half your body weight in ounces.

Vitamins

Vitamins are organic compounds that are essential for normal physiologic processes in the body. Before their detailed chemical structures were known, vitamins were named by being given a letter. They are generally still referred to by that letter as well as by their chemical name, for example, vitamin C or ascorbic acid.

Vitamins are categorized as either water-soluble or fat-soluble based on how they are dissolved in the body. Water soluble vitamins are dissolved in water and absorbed during digestion. Excess water-soluble vitamins are excreted through urine. Fat-soluble vitamins are absorbed through the digestive process with the help of fats (lipids). Excess fat-soluble vitamins can build up in the body and become toxic. Vitamin supplements can be dangerous particularly with fat-soluble vitamins because people can overdose.

A balanced diet includes all of the vitamins and minerals a person needs daily.

Water-Soluble Vitamins

There are nine water-soluble vitamins: Vitamin C, and eight Vitamin B’s.

Fat-Soluble Vitamins

There are four fat-soluble vitamins: Vitamins A, D, E, and K.

Minerals

Minerals are essential, non-caloric nutrients that are in all of our food and are essential for normal physiologic processes in the body. Minerals are micronutrients, which means humans only need to eat them in small quantities. Minerals assist body functions that range from bone strength to regulating your heartbeat.

When plants take up the water through their roots, dissolved minerals from within the soil are absorbed by the plant. When people eat plants, they are ingesting minerals found in the plant. Animals are able to concentrate minerals in their tissues, so meats and other foods derived from animals often contain a higher concentration of minerals.

There are two categories of minerals: major minerals and trace minerals. The classification of a mineral as major or trace depends on how much of the mineral the body needs.

Major minerals include:

- Calcium

- Phosphorus

- Sodium

- Potassium

- Magnesium

Trace minerals include:

- Iron

- Fluoride

- Zinc

- Copper

- Iodine

- Manganese

- Chloride

- Selenium

Vitamin and Mineral Supplements

Vitamin and mineral supplements exist, but are not as effective as getting minerals from whole foods. There are two types of supplement: whole food supplements and synthetic supplements.

Whole food supplements are produced by taking vitamins and minerals straight from natural sources: soil, rocks, or plant/food sources; whereas, synthetic minerals are made in a lab. While synthetic mineral supplements mimic the chemical structure of vitamins and minerals, they are probably not exact copies. That means the body may not recognize the synthetic mineral structure and does not absorb the mineral efficiently. No supplements, including vitamins and minerals, are approved by the FDA. Only prescription drugs are approved by the FDA. A healthy balanced diet can provide all the vitamins and minerals needed.

Food and Metabolism

The amount of energy that is needed or ingested per day is measured in calories. A calorie is the amount of heat it takes to raise 1 g of water by 1 °C. On average, a person needs 1500 to 2000 calories per day to sustain (or carry out) daily activities. The total number of calories needed by one person is dependent on his/her body mass, % lean mass, age, height, gender, activity level, and the amount of exercise per day. If exercise is a regular part of one’s day, more calories are required. As a rule, people underestimate the number of calories ingested and overestimate the amount they burn through exercise. This can lead to ingestion of too many calories per day. The accumulation of an extra 3500 calories adds one pound of weight. If an excess of 200 calories per day is ingested, one extra pound of body weight will be gained every 18 days. At that rate, an extra 20 pounds can be gained over the course of a year. Of course, this increase in calories could be offset by increased exercise. Running or jogging one mile burns about 100 calories.

The type of food ingested also affects the body’s metabolic rate. Processing of carbohydrates requires less energy than processing of proteins. In fact, the breakdown of carbohydrates requires the least amount of energy; whereas, the processing of proteins demands the most energy. In general, the amount of calories ingested and the amount of calories burned determines the overall weight. To lose weight, the number of calories burned per day must exceed the number ingested. Calories are in almost everything one ingests, so when considering calorie intake, beverages must also be considered.

Planning a Diet

The definition of diet is anything that is consumed by a particular person or people on a regular basis. That means if someone routinely drinks coffee in the morning, that is part of his/her diet. If a person consistently eats a Big Mac from McDonald’s, that is part of his/her diet.

It is clear that food choices influence short-term and long-term health. That is why it is so important to make wise choices in what one eats on a regular basis. If a person chooses to have a diet high in calories without balancing energy use, that person can expect to put on unhealthy weight. A diet that is high in fiber, with the appropriate amount of calories and proper amounts of the macronutrients, will contribute to a healthy body.

any times, the term diet is thought of as a method to lose weight or to change body shape. However, it is important to focus on the nutritional concepts listed below, so long-term health can be achieved.

Decisions about nutrition can be difficult. Knowing and using scientific research can lead to better health. Public health organizations have developed tools based on nutritional science to help people design healthy diets. These tools should be used as guidelines for each individual with the awareness that everyone is different and therefore has different needs. Everyone, regardless of age, size, shape, physique, can benefit from learning and utilizing the following tools:

Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range

The Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR) describes the proportions of daily caloric intake that should be carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins. Basically the AMDR provides guidelines on how many macronutrient calories one should consume a day.

According to the AMDR, the range of caloric intake in a daily diet should be:

- Carbohydrates: 45-65%

- Lipids: 20-35%

- Proteins: 10-35%

These ranges give enough variance to serve all genders and activity levels.

Dietary Reference Intakes

The Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI’s) are reference values of nutrient intake that help with nutrition planning and assessment of healthy individuals. There are four measures that together comprise the DRI:

- Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA): the average daily dietary intake level that is sufficient to meet the nutrient requirement of nearly all (about 97%) healthy individuals in a group. This is the basic quantity of a nutrient recommended.

- Adequate Intake (AI): a value based on observed or experimentally determined approximations of nutrient intake by a group (or groups) of healthy people—used when an RDA cannot be determined. This is the minimum amount of a nutrient needed for maintaining health.

- Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL): the highest level of daily nutrient intake that is likely to pose no risk of adverse health effects to almost all individuals in the general population. As intake increases above the UL, the risk of adverse effects increases. This is the maximum that would be consumed prior to developing negative effects of eating too much. This is not a level that is met, but rather one that is avoided to prevent a decrease in health.

- Estimated Average Requirement (EAR): a nutrient intake value that is estimated to meet the requirement of half the healthy individuals in a group. These nutrient values should be used as goals for dietary intake for health.

4 Key Concepts for Personalizing a Healthy Diet

Personalizing meal plans can be extremely beneficial psychologically as well as physically. Knowing that one is eating healthy reduces some of the subconscious doubts about doing what needs to be done to be well. However, as with every healthy practice, there can be pitfalls. To help avoid these, there are 4 approaches that can be taken:

- Assessing and changing your current diet

- Staying committed to a healthy diet

- Try additions and substitutions to bring your current diet closer to your goals

- Plan ahead for challenging situations

Planning Healthy Meals

Individual requirements for nutrients vary considerably depending on factors such as age and gender. Other relevant factors are size, metabolic rate, and occupation. A farmer would have a different dietary need than someone in a sedentary occupation. The body also has stores of certain nutrients (fat-soluble vitamins, for example) so that variations in daily intake of such nutrients can be accommodated.

When considering dietary needs, various techniques have been established by health officials to assist people in choosing foods and food amounts wisely. Choose My Plate is a graphic representation of what a healthy plate of food might look like.

Other tools, such as meal planning guides can easily be found and utilized online or through apps.

Nutrition Labels

Perhaps one of the most effective tools provided to consumers is the nutrition label that is, by law, on all food packaging. This information can be useful for evaluating the nutrient content of food and planning healthy meals.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires packaged foods to have a label that helps consumers make educated decisions about the foods they purchase. The label provides caloric, macronutrient, and some micronutrient content of the food. Labels also indicate ingredients and manufacturer information.

FYI: Food labels do not provide all nutritional information; they just include the basics to help consumers make healthy food decisions.

Information On Food Labels

- Name of product: Sometimes the name of the product includes important information. For example some brands are vegetarian, kosher, gluten-free, etc. It is also important to compare/contrast ingredients in generic and brand name foods

- Serving Size: It’s important to pay attention to how many servings a package contains. Many packages contain multiple servings.

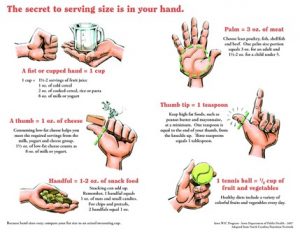

Figure 4. Using your hand to determine serving size

- Calories: Pay attention to whether the caloric content of the food is per serving or per package. Also, some food labels indicate calories before or after preparation.

- Fats: The food label includes all fats. Note that the label indicates different types of fats.

- Cholesterol: Dietary cholesterol is a major factor in cardiovascular health. Limiting the intake of cholesterol can prevent heart disease.

- Sodium: Another major factor in promoting good health is limiting the amount of sodium intake to less than 2000mg per day.

- Carbohydrates: The food label includes simple and complex carbohydrates. Note that the label indicates different types of carbohydrates. Carbohydrates should make up 45-65% of a persons diet while keeping grams of sugar below 25-30 grams per day.

- Proteins: Protein intake needs to be carefully monitored because over or under consumption of protein can cause severe issues.

- Vitamins and Minerals: There are four vitamins and minerals (Vitamin D, Calcium, Iron, and Potassium) that are required on food labels; however, the label might include more than these four.

- Ingredients: The ingredients are listed in order of their content per volume. If sugar is listed as the first ingredient, there is more sugar in the food than any other ingredient. The last ingredient has the least amount in the food.

- Name of manufacturer: In addition to the Nutrition Facts, the food label includes the name and contact information for the manufacturer as required by law.

- Allergens: Food manufacturers are required to draw specific attention to common allergens such as nuts, milk products, soy, etc. There is no specific location for allergen information, but it should be someplace on the packaging.

Figure 5. Nutrition Facts

To learn additional details about all of the information contained within the Nutrition Facts panel, see the following website: http://www.fda.gov/Food/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/NFLPM/ucm274593.htm

Dietary Food Trends

Hundreds of years ago, when food was less accessible and daily life required much more physical activity, people worried less about obesity and more about simply getting enough to eat. In today’s industrialized nations, conveniences have solved some problems and introduced new ones, including the hand-in-hand obesity and diabetes epidemics. Fad diets gained popularity as more North Americans struggled with excess pounds. However, new evidence-based approaches that emphasize more holistic measures are on the rise. These new dietary trends encourage those seeking to lose weight to eat healthy, whole foods first, while adopting a more active lifestyle. These sound practices put dietary choices in the context of wellness and a healthier approach to life.

Table 2: The Pros and Cons of Seven Popular Diets

| Diet | Pros | Cons |

| DASH Diet |

|

|

| Gluten-Free Diet |

|

|

| Low-Carb Diet |

|

|

| Mediterranean Diet |

|

|

| Raw Food Diet |

|

|

| Vegetarianism and Veganism |

|

|

Weight Management

Achieving and sustaining appropriate body weight across the lifespan is vital to maintaining good health and quality of life. Many behavioral, environmental, and genetic factors have been shown to affect a person’s body weight. Calorie balance over time is the key to weight management. Calorie balance refers to the relationship between calories consumed from foods and beverages and calories expended in normal body functions (i.e., metabolic processes) and through physical activity. People cannot control the calories expended in metabolic processes, but they can control what they eat and drink, as well as how many calories they use in physical activity.

Calories consumed must equal calories expended for a person to maintain the same body weight. Consuming more calories than expended will result in weight gain. Conversely, consuming fewer calories than expended will result in weight loss. This can be achieved over time by eating fewer calories, being more physically active, or, best of all, a combination of the two.

Maintaining a healthy body weight and preventing excess weight gain throughout the lifespan are highly preferable to losing weight after weight gain. Once a person becomes obese, reducing body weight back to a healthy range requires significant effort over a span of time, even years. People who are most successful at losing weight and keeping it off do so through continued attention to calorie balance.

The current high rates of overweight and obesity among virtually all subgroups of the population in the United States demonstrate that many Americans are in calorie imbalance—that is, they consume more calories than they expend. To curb the obesity epidemic and improve their health, Americans need to make significant efforts to decrease the total number of calories they consume from foods and beverages and increase calorie expenditure through physical activity. Achieving these goals will require Americans to select a healthy eating pattern that includes nutrient-dense foods and beverages they enjoy, meets nutrient requirements, and stays within calorie needs. In addition, Americans can choose from a variety of strategies to increase physical activity.

Key Recommendations

- Prevent and/or reduce overweight and obesity through improved eating and physical activity behaviors.

- Control total calorie intake to manage body weight. For people who are overweight or obese, this will mean consuming fewer calories from foods and beverages.

- Increase physical activity and reduce time spent in sedentary behaviors.

- Maintain appropriate calorie balance during each stage of life—childhood, adolescence, adulthood, pregnancy and breastfeeding, and older age.

Balancing Calories and Eating Healthfully

Understanding Calories Needs

The total number of calories a person needs each day varies depending on a number of factors, including the person’s age, gender, height, weight, and level of physical activity. This number is called basal metabolic rate, or the base number of calories to survive and carry out basic functions. In addition, a desire to lose, maintain, or gain weight affects how many calories should be consumed. Estimates range from 1,600 to 2,400 calories per day for adult women and 2,000 to 3,000 calories per day for adult men, depending on age and physical activity level. Within each age and gender category, the low end of the range is for sedentary individuals; the high end of the range is for active individuals. Due to reductions in basal metabolic rate that occurs with aging, calorie needs generally decrease for adults as they age. Estimated needs for young children range from 1,000 to 2,000 calories per day, and the range for older children and adolescents varies substantially from 1,400 to 3,200 calories per day, with boys generally having higher calorie needs than girls. These are only estimates, and more accurate calorie needs may be determined using the Harris Benedict Equation shown below:

- Step 1 – Calculating the Harris–Benedict BMR

The original Harris–Benedict equations published in 1918 and 1919.

| BMR calculation for men | BMR = 66 + ( 6.2 x weight in pounds ) + ( 12.7 x height in inches ) – ( 6.76 x age in years ) |

| BMR calculation for women | BMR = 655 + ( 4.35 x weight in pounds ) + ( 4.7 x height in inches ) – ( 4.7 x age in years ) |

- Step 2 – Determine Recommended Intake

The following table enables calculation of an individual’s recommended daily kilocalorie intake to maintain current weight.[4]

| Little to no exercise | Daily kilocalories needed = BMR x 1.2 |

| Light exercise (1–3 days per week) | Daily kilocalories needed = BMR x 1.375 |

| Moderate exercise (3–5 days per week) | Daily kilocalories needed = BMR x 1.55 |

| Heavy exercise (6–7 days per week) | Daily kilocalories needed = BMR x 1.725 |

| Very heavy exercise (twice per day, extra heavy workouts) | Daily kilocalories needed = BMR x 1.9 |

Knowing one’s daily calorie needs may be a useful reference point for determining whether the calories that a person eats and drinks are appropriate in relation to the number of calories needed each day. The best way for people to assess whether they are eating the appropriate number of calories is to monitor body weight and adjust calorie intake and participation in physical activity based on changes in weight over time. 3500 calories is equal to 1 pound of fat. A calorie deficit of 500 calories or more per day is a common initial goal for weight loss for adults. However, maintaining a smaller deficit can have a meaningful influence on body weight over time. The effect of a calorie deficit on weight does not depend on how the deficit is produced—by reducing calorie intake, increasing expenditure, or both. Yet, in research studies, a greater proportion of the calorie deficit is often due to decreasing calorie intake with a relatively smaller fraction due to increased physical activity.

Table 2. Estimated Calorie Needs Per Day By Age, Gender, and Physical Activity Level*

Estimated amounts of calories needed to maintain calorie balance for various gender and age groups at three different levels of physical activity. The estimates are rounded to the nearest 200 calories. An individual’s calorie needs may be higher or lower than these average estimates.

| gender | age (years) |

sedentary |

Physical activity level*

moderately active |

active |

| child (female and male) | 2–3 | 1,000–1,200c | 1,000–1,400c | 1,000–1,400c |

| female | 4–8 | 1,200–1,400 | 1,400–1,600 | 1,400–1,800 |

| 9–13 | 1,400–1,600 | 1,600–2,000 | 1,800–2,200 | |

| 14–18 | 1,800 | 2,000 | 2,400 | |

| 19–30 | 1,800–2,000 | 2,000–2,200 | 2,400 | |

| 31–50 | 1,800 | 2,000 | 2,200 | |

| 51+ | 1,600 | 1,800 | 2,000–2,200 | |

| male | 4–8 | 1,200–1,400 | 1,400–1,600 | 1,600–2,000 |

| 9–13 | 1,600–2,000 | 1,800–2,200 | 2,000–2,600 | |

| 14–18 | 2,000–2,400 | 2,400–2,800 | 2,800–3,200 | |

| 19–30 | 2,400–2,600 | 2,600–2,800 | 3,000 | |

| 31–50 | 2,200–2,400 | 2,400–2,600 | 2,800–3,000 | |

| 51+ | 2,000–2,200 | 2,200–2,400 | 2,400–2,800 | |

a. Based on Estimated Energy Requirements (EER) equations, using reference heights (average) and reference weights (healthy) for each age/gender group. For children and adolescents, reference height and weight vary. For adults, the reference man is 5 feet 10 inches tall and weighs 154 pounds. The reference woman is 5 feet 4 inches tall and weighs 126 pounds. EER equations are from the Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2002.

b. Sedentary means a lifestyle that includes only the light physical activity associated with typical day-to-day life. Moderately active means a lifestyle that includes physical activity equivalent to walking about 1.5 to 3 miles per day at 3 to 4 miles per hour, in addition to the light physical activity associated with typical day-to-day life. Active means a lifestyle that includes physical activity equivalent to walking more than 3 miles per day at 3 to 4 miles per hour, in addition to the light physical activity associated with typical day-to-day life.

c. The calorie ranges shown are to accommodate needs of different ages within the group. For children and adolescents, more calories are needed at older ages. For adults, fewer calories are needed at older ages.

d. Estimates for females do not include women who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Individual Foods and Beverages and Body Weight

For calorie balance, the focus should be on total calorie intake. As individuals vary a great deal in their dietary intake, the best advice is to monitor diet and replace foods higher in calories with nutrient-dense foods and beverages relatively low in calories. The following guidance may help individuals control their total calorie intake and manage body weight:

- Increase intake of whole grains, vegetables, and fruits: adults who eat more whole grains, particularly those higher in dietary fiber, have a lower body weight compared to adults who eat fewer whole grains. Increased intake of vegetables and/or fruits may protect against weight gain.

- Reduce intake of sugar-sweetened beverages: This can be accomplished by drinking fewer and/or consuming smaller portions. Children and adolescents who consume more sugar-sweetened beverages have higher body weight compared to those who drink less. Sugar-sweetened beverages provide excess calories and few essential nutrients to the diet and should only be consumed occasionally.

Developing Healthy Eating Patterns

Because people consume a variety of foods and beverages throughout the day as meals and snacks, a growing body of research has begun to describe overall eating patterns that help promote calorie balance and weight management. One aspect of these patterns that has been researched is the concept of calorie density, or the amount of calories provided per unit of food weight. Foods high in water and/or dietary fiber typically have fewer calories per gram and are lower in calorie density, while foods higher in fat are generally higher in calorie density. A dietary pattern low in calorie density is characterized by a relatively high intake of vegetables, fruit, and dietary fiber and a relatively low intake of total fat, saturated fat, and added sugars. Eating patterns that are low in calorie density improve weight loss and weight maintenance, and also may be associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes in adults.

Although total calories consumed is important for calorie balance and weight management, it is important to consider the nutrients and other healthful properties of food and beverages, as well as their calories, when selecting an eating pattern for optimal health.

- When choosing carbohydrates, Americans should emphasize naturally occurring carbohydrates, such as those found in whole grains, beans and peas, vegetables, and fruits, especially those high in dietary fiber, while limiting refined grains and intake of foods with added sugars.

- For protein, plant-based sources and/or animal-based sources can be incorporated into a healthy eating pattern. However, some protein products, particularly some animal-based sources, are high in saturated fat, so non-fat, low-fat, or lean choices should be selected.

- Fat intake should emphasize monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, such as those found in seafood, nuts, seeds, and oils.

Americans should move toward more healthful eating patterns. Overall, as long as foods and beverages consumed meet nutrient needs and calorie intake is appropriate, individuals can select an eating pattern that they enjoy and can maintain over time. Individuals should consider the calories from all foods and beverages they consume, regardless of when and where they eat or drink.

Calorie Balance: Physical Activity

Physical activity is the other side of the calorie balance equation and should be considered when addressing weight management. Regular participation in physical activity not only reduces risk of disease, it also helps people maintain a healthy weight and prevent excess weight gain. Further, physical activity, particularly when combined with reduced calorie intake, may aid weight loss and maintenance of weight loss.

Physical Fitness

Being physically active is one of the most important steps that Americans of all ages can take to improve their health. Physical activity is beneficial for healthy people, people at risk of developing chronic diseases, and people with current chronic conditions or disabilities. Studies by the US Department of Health and Human Services have examined the role of physical activity in many groups—men and women, children, teens, adults, older adults, people with disabilities, and women during pregnancy and the postpartum period. These studies have focused on the role that physical activity plays in many health outcomes, such as coronary artery disease, diabetes, stroke, osteoporosis, high blood sugar, high cholesterol and depression.

Health Benefits Associated with Regular Physical Activity

Table 1

| Health Benefits Associated with Regular Physical Activity in Adults and Older Adults | ||

| Strong Evidence | Moderate to Strong Evidence | Moderate Evidence |

| • Lower risk of early death

• Lower risk of coronary heart disease • Lower risk of stroke • Lower risk of high blood pressure • Lower risk of adverse blood lipid profile • Lower risk of type 2 diabetes • Lower risk of metabolic syndrome • Lower risk of colon cancer • Lower risk of breast cancer • Prevention of weight gain • Weight loss, particularly when combined with reduced calorie intake • Improved cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness • Prevention of falls • Reduced depression • Better cognitive function (for older adults) |

• Better functional health (for older adults)

• Reduced abdominal obesity

|

• Lower risk of hip fracture

• Lower risk of lung cancer • Lower risk of endometrial cancer • Weight maintenance after weight loss • Increased bone density • Improved sleep quality |

These studies have also prompted questions as to what type and how much physical activity is needed for various health benefits. That led to the development of The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, which gives guidance on the amount of physical activity that will provide health benefits for all Americans. Although some health benefits seem to begin with as little as 60 minutes (1 hour) a week, research shows that a total amount of 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) a week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, such as brisk walking, consistently reduces the risk of many chronic diseases and other adverse health outcomes. For more details on the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans please see the table below:

Table 3

| For Important Health Benefits Adults Need at Least: | ||

| 2 hours and 30 minutes (150 minutes) of moderate aerobic activity every week (i.e., brisk walking) every week; | AND | Muscle-strengthening activities on 2 or more days a week that work all major muscle groups (legs hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, and arms) |

| OR | ||

| 1 hour and 15 minutes (75 minutes) of vigorous intensity aerobic activity (i.e., jogging or running) every week; | ||

| OR | ||

| An equivalent mix of moderate-and-vigorous-intensity aerobic activity |

Although the Guidelines focus on the health benefits of physical activity, these benefits are not the only reason why people are active. Physical activity gives people a chance to have fun, be with friends and family, enjoy the outdoors, improve their personal appearance, and improve their fitness so that they can participate in more intensive physical activity or sporting events. Some people are active because it gives them certain health benefits (such as feeling more energetic). The Guidelines encourage people to be physically active for any and all reasons that are meaningful for them. Nothing in the Guidelines is intended to mean that health benefits are the only reason to do physical activity.

Health Related Components of Physical Fitness

In many studies related to physical fitness and health, researchers have focused on exercise, as well as on the more broadly defined concept of physical activity. Physical activity is defined by the World Health Organization as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure, while exercise is a form of physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and performed with the goal of improving health or fitness. So, although all exercise is physical activity, not all physical activity is exercise. Although physical activity and exercise are defined concepts, the ultimate focus of the health related components of physical fitness is to provide a framework for components that are necessary for good health. They are cardiorespiratory (CR) endurance (also called aerobic endurance), flexibility, muscular strength, muscular endurance, and body composition.

Cardiorespiratory Endurance

- Aerobic endurance: The ability of the heart, blood vessels, and lungs to work together to accomplish three goals: 1) deliver oxygen to body tissues; 2) deliver nutrients; 3) remove waste products. CR endurance exercises involve large muscle groups in prolonged, dynamic movement (ex. running, swimming, etc)

Table 4

| Examples of Different Aerobic Physical Activities and Intensities | |

| Moderate Intensity | Vigorous Intensity |

| · Walking briskly (3 miles per hour or faster, but not race-walking)

· Water aerobics · Bicycling slower than 10 miles per hour · Tennis (doubles) · Ballroom dancing · General gardening

|

· Racewalking, jogging, or running

· Swimming laps · Tennis (singles) · Aerobic dancing · Bicycling 10 miles per hour or faster · Jumping rope · Heavy gardening (continuous digging or hoeing, with heart rate increases) · Hiking uphill or with a heavy backpack |

Muscular Strength and Endurance

- Muscular strength: The ability of muscles to exert maximal effort.

- Muscular endurance: The ability of muscles to exert submaximal effort repetitively (contract over and over again or hold a contraction for a long time).

Activities for Muscular Strength and Endurance

These kind of activities, which includes resistance training and lifting weights, causes the body’s muscles to work or hold against an applied force or weight. These activities often involve relatively heavy objects, such as weights, which are lifted multiple times to train various muscle groups. Muscle-strengthening activity can also be done by using elastic bands or body weight for resistance (climbing a tree or doing push-ups, for example). Activities for Muscular Strength and Endurance also has three components:

Muscle-strengthening activities provide additional benefits not found with aerobic activity. The benefits of muscle-strengthening activity include increased bone strength and muscular fitness. Muscle-strengthening activities can also help maintain muscle mass during a program of weight loss.

Flexibility

Flexibility is the ability of moving a joint through the range of motion. Flexibility is an important part of physical fitness. Stretching exercises are effective in increasing flexibility, and thereby can allow people to more easily do activities that require greater flexibility. Flexibility activities also reduce risk of joint pain as well as muscle and joint injury. Time spent doing flexibility activities by themselves does not count toward meeting the aerobic or muscle-strengthening Guidelines. Although there are not specific national guidelines for flexibility, adults should do flexibility exercises at least two or three days each week to improve range of motion. This can be done by holding a stretch for 10-30 seconds to the point of tightness or slight discomfort. Repeat each stretch two to four times, accumulating 60 seconds per stretch.

Body Composition

The percentage of the body composed of lean tissue (muscle, bone, fluids, etc.) and fat tissue. Changes in body composition usually occur as a result of improvements in the other components of health related physical fitness, as well as changes in eating habits.

Adding Physical Activity to Your Life

Overcoming Barrier to Being Physical Active

Given the health benefits of regular physical activity, we might have to ask why two out of three (60%) Americans are not active at recommended levels.

Many technological advances and conveniences that have made our lives easier and less active, as well as many personal variables, including physiological, behavioral, and psychological factors, may affect our plans to become more physically active. In fact, the 10 most common reasons adults cite for not adopting more physically active lifestyles are (Sallis and Hovell, 1990; Sallis et al., 1992):

- Do not have enough time to exercise

- Find it inconvenient to exercise

- Lack self-motivation

- Do not find exercise enjoyable

- Find exercise boring

- Lack confidence in their ability to be physically active (low self-efficacy)

- Fear being injured or have been injured recently

- Lack self-management skills, such as the ability to set personal goals, monitor progress, or reward progress toward such goals

- Lack encouragement, support, or companionship from family and friends, and

- Do not have parks, sidewalks, bicycle trails, or safe and pleasant walking paths convenient to their homes or offices.

Understanding common barriers to physical activity and creating strategies to overcome them may help you make physical activity part of your daily life.

Creating Your Own Fitness Program

The first step to implementing a fitness program is to identify your goals. Goals should be Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic and Time-bound (SMART). Progress can be difficult to track if goals are vague and open-ended, such as “I will exercise more.” Here is an example of a SMART goal for fitness:

- Specific: “I will walk for 30 minutes a day 3-5 days per week”

- Measurable: “I will improve my resting heart rate over the next month”

- Attainable: “I have the ability to se aside 30 minutes on 3-5 days per week to walk”

- Realistic: “I will increase my walking to 45 minutes per day in one month”

- Time Bound: “I will try this walking program for one month and then reassess my goals”

You can also make a SMART Goal in one statement, such as “I will walk for 30 minutes 3-5 days per week for the next month in order to improve my resting heart rate.”

Achieving Your Physical Activities: The Possibilities are endless

These examples show how it’s possible to meet the Guidelines by doing moderate-intensity or vigorous-intensity activity or a combination of both. Physical activity at this level provides substantial health benefits.

Ways to get the equivalent of 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity a week plus muscle-strengthening activities:

- Thirty minutes of brisk walking (moderate intensity) on 5 days, exercising with resistance bands (muscle strengthening) on 2 days;

- Twenty-five minutes of running (vigorous intensity) on 3 days, lifting weights on 2 days (muscle strengthening);

- Thirty minutes of brisk walking on 2 days, 60 minutes (1 hour) of social dancing (moderate intensity) on 1 evening, 30 minutes of mowing the lawn (moderate intensity) on 1 afternoon, heavy gardening (muscle strengthening) on 2 days;

- Thirty minutes of an aerobic dance class on 1 morning (vigorous intensity), 30 minutes of running on 1 day (vigorous intensity), 30 minutes of brisk walking on 1 day (moderate intensity), calisthenics (such as sit-ups, push-ups) on 3 days (muscle strengthening);

- Thirty minutes of biking to and from work on 3 days (moderate intensity), playing softball for 60 minutes on 1 day (moderate intensity), using weight machines on 2 days (muscle-strengthening on 2 days); and

- Forty-five minutes of doubles tennis on 2 days (moderate intensity), lifting weights after work on 1 day (muscle strengthening), hiking vigorously for 30 minutes and rock climbing (muscle strengthening) on 1 day.

Increase Physical Activity Gradually Over Time

Scientific studies indicate that the risk of injury to bones, muscles, and joints is directly related to the gap between a person’s usual level of activity and a new level of activity. The size of this gap is called the amount of overload. Creating a small overload and waiting for the body to adapt and recover reduces the risk of injury. When amounts of physical activity need to be increased to meet the Guidelines or personal goals, physical activity should be increased gradually over time, no matter what the person’s current level of physical activity. The following recommendations give general guidance for inactive people and those with low levels of physical activity on how to increase physical activity:

- Start with relatively moderate-intensity aerobic activity. Avoid vigorous-intensity activity, such as shoveling snow or running until you feel comfortable at this intensity. Adults with a low level of fitness may need to start with light activity, or a mix of light- to moderate-intensity activity.

- First, increase the number of minutes per session (duration), and the number of days per week (frequency) of moderate-intensity activity. Later, if desired, increase the intensity.

- Pay attention to the relative size of the increase in physical activity each week, as this is related to injury risk. For example, a 20-minute increase each week is safer for a person who does 200 minutes a week of walking (a 10 percent increase), than for a person who does 40 minutes a week (a 50 percent increase).

Support your activity by eating whole, nutritious foods and drinking plenty of water. Healthy eating and physical activity reduces risk of disease, improves self-perception and adds to an overall sense of wellbeing. How can you add some of these behaviors into your everyday life?

Check for Understanding

- What are the macronutrients and what function do they serve in the body?

- What modifications can a person make to improve the micronutrient content in their diet?

- What is a safe caloric deficit for weight loss that still allows for adequate nutrient intake and successful weight loss?

- What components of fitness are important to include in a fitness plan?

- What are some simple ways a person could increase the amount of physical activity in their daily routine?