2 Female Reproductive Anatomy and Physiology

Chapter Objectives

- Explore common methods of sex education in the US and potential benefits/drawbacks

- Identify anatomical structures of the female reproductive system

- Describe hormonal and physiological changes that take place during ovulation and menstruation

- Describe the hormonal and physiological changes that take place during fertilization and implantation

- Explore dysfunction in female reproductive anatomy and potential symptoms/testing

The Female Reproductive System

“Menstrual blood is the only source of blood that is not traumatically induced. Yet, in modern society, this is the most hidden blood, the one so rarely spoken of and almost never seen, except privately by women. ~ Judy Grahn

Sex Education in the US

How did you first learn about your private body? When did you learn how it functioned and how to care for it? For many, these are discussions that take place at home when parents feel their child is old enough to need this information. It is often coined “the talk” and is dreaded by old and young alike.

Maybe your parents did not discuss such things but you received a “handy pamphlet” or a 45-minute video in 5th grade to explain your assigned gender along with some rules for future actions. Maybe books, the internet, friends or older siblings were your guide. Rarely are children taught about their own sexual anatomy in a open and comfortable way. Why do we maintain this stigma with certain parts of our bodies?

Consider your own thoughts and beliefs on when children should learn about sexual anatomy and physiology, sexuality, and safe sex. How will the experiences surrounding way a child learns about their sexual health impact future health choices?

Female Reproductive Anatomy

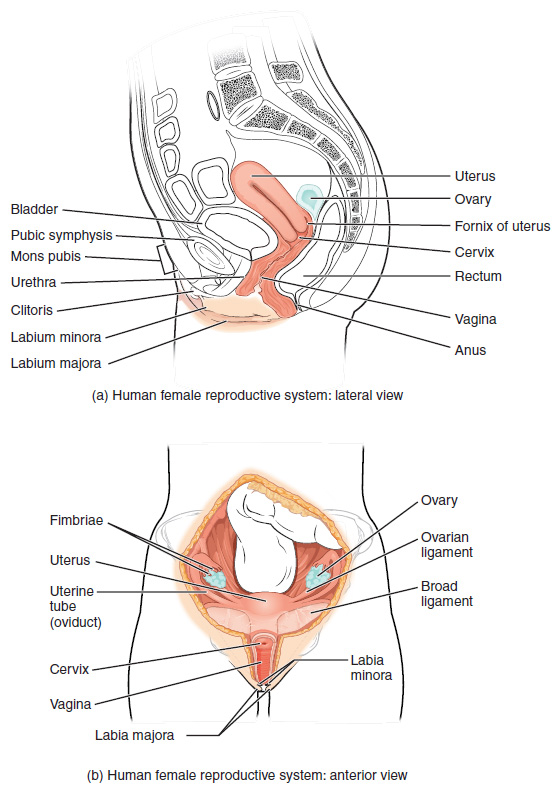

The female reproductive system functions to produce a female egg (gamete), reproductive hormones, support a developing fetus and deliver it into the outside world. Unlike its male counterpart, the female reproductive system is located primarily inside the pelvic cavity (Figure 1). Let’s look at some of the structures of the female reproductive system.

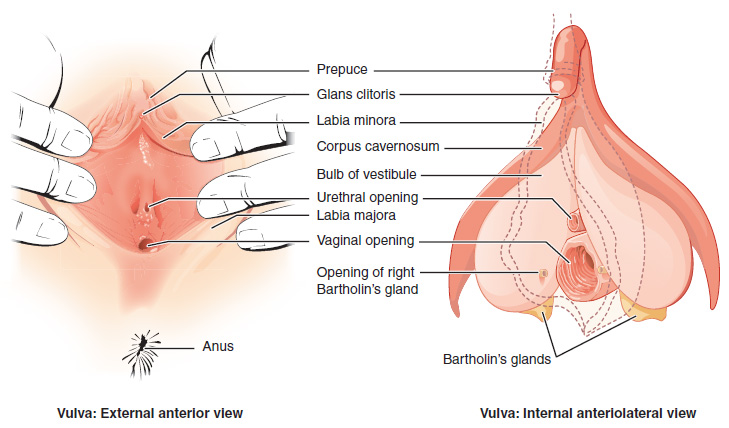

External Female Genitalia

The external female reproductive structures are referred to collectively as the vulva (Figure 2). The mons pubis is a pad of fat that is located over the pubic bone. After puberty, it becomes covered in pubic hair. The labia majora (labia = “lips”; majora = “larger”) are folds of hair-covered skin that begin just posterior to the mons pubis. The thinner and more pigmented labia minora (labia = “lips”; minora = “smaller”) lie inside the labia majora. Labia majora and minora serve to protect the female urethra and the entrance to the female reproductive tract.

The forward portions of the labia minora come together to encircle the clitoris (or glans clitoris), an organ that originates from the same cells as the glans penis and has abundant nerves that make it important in sexual sensation and orgasm. The hymen is a thin membrane that sometimes partially covers the entrance to the vagina. An intact hymen cannot be used as an indication of “virginity”; even at birth, this is only a partial membrane, as menstrual fluid and other secretions must be able to exit the body, regardless of penile–vaginal intercourse. The vaginal opening is located between the opening of the urethra and the anus. It is flanked by outlets to the Bartholin’s glands (or greater vestibular glands).

Internal Female Anatomy

The vagina, Figure 1, is a muscular canal (approximately 10 cm long) that serves as the entrance to the reproductive tract. It also serves as the exit from the uterus during menses and childbirth. The thin, perforated hymen can partially surround the opening to the vaginal orifice. The hymen can be ruptured with strenuous physical exercise, penile–vaginal intercourse, and childbirth. The Bartholin’s glands and the lesser vestibular glands (located near the clitoris) secrete mucus, which keeps the vestibular area moist.

The vagina is home to a normal population of microorganisms that help to protect against infection by bacteria, yeast, or other organisms that can enter the vagina. In a healthy woman, the most predominant type of vaginal bacteria is from the genus Lactobacillus. This family of beneficial bacterial flora secretes lactic acid, and thus protects the vagina by maintaining an acidic pH (below 4.5). Potential pathogens are less likely to survive in these acidic conditions. Lactic acid, in combination with other vaginal secretions, makes the vagina a self-cleansing organ. Douching—or washing out the vagina with fluid—can disrupt the normal balance of healthy microorganisms, and actually increase a woman’s risk for infections and irritation. Indeed, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend that women do not douche, and that they allow the vagina to maintain its normal healthy population of protective microbial flora.

The ovaries are the female gonads (organ that produces female sex cells/eggs) (see Figure 1) each about the size of an almond. The ovaries are located within the pelvic cavity and attached to the uterus via the ovarian ligament (not the fallopian tubes).

The uterine tubes (also called fallopian tubes or oviducts) serve as passage for the ovum from the ovary to the uterus. Each of the two uterine tubes is close to, but not directly connected to, the ovary. The middle region of the tube, called the ampulla, is where fertilization often occurs. Unlike sperm, oocytes lack flagella (tail), and therefore cannot move on their own. So how do they travel into the uterine tube and toward the uterus? High concentrations of estrogen that occur around the time of ovulation induce contractions of the smooth muscle along the length of the uterine tube. These contractions occur every 4 to 8 seconds, and the result is a coordinated movement that sweeps the surface of the ovary and the pelvic cavity.

If the oocyte is successfully fertilized, the resulting zygote will begin to divide into two cells, then four, and so on, as it makes its way through the uterine tube and into the uterus. There, it will implant and continue to grow. If the egg is not fertilized, it will simply degrade—either in the uterine tube or in the uterus, where it may be shed with the next menstrual period.

The uterus is the muscular organ that nourishes and supports the growing embryo. Its average size is approximately approximately 2 in. by 3 in. when a female is not pregnant. It has three sections. The highest point is called the fundus. The middle section of the uterus is called the body of uterus. The cervix is the narrow bottom portion of the uterus that projects into the vagina. The cervix produces mucus secretions that become thin and stringy under the influence of estrogen which can facilitate sperm movement through the reproductive tract.

The wall of the uterus is made up of three layers. The perimetrium (outer layer), myometrium (muscle layer) and endometrium (part of this layer is shed during menses). Most of the uterus is myometrial tissue, and the muscle fibers run horizontally, vertically, and diagonally, allowing the powerful contractions that occur during labor and the less powerful contractions (or cramps) that help to expel menstrual blood during a woman’s period.

Female Reproductive Physiology – The Menstrual Cycle

Menstruation

The menstrual cycle is the process by which a woman’s body gets ready for the chance of a pregnancy each month. The average menstrual cycle is 28 days from the start of one to the start of the next, but it can range from 21 days to 35 days. Most menstrual periods last from three to five days. In the United States, most girls start menstruating at age 12, but girls can start menstruating between the ages of 8 and 16. Menarche is a term referring to the first occurrence of mensuration.

When a woman menstruates, her body sheds the lining of the uterus (part of the endometrium). Menstrual blood flows from the uterus through the small opening in the cervix and passes out of the body through the vagina (see how the menstrual cycle works below).

The regular occurrence of menses is called the menstrual cycle. Having a regular menstrual cycle is a sign that reproductive organs are working properly. In addition to preparing the body for a pregnancy, this cycle provides important body chemicals (hormones) for a number of body functions related and not related to pregnancy.

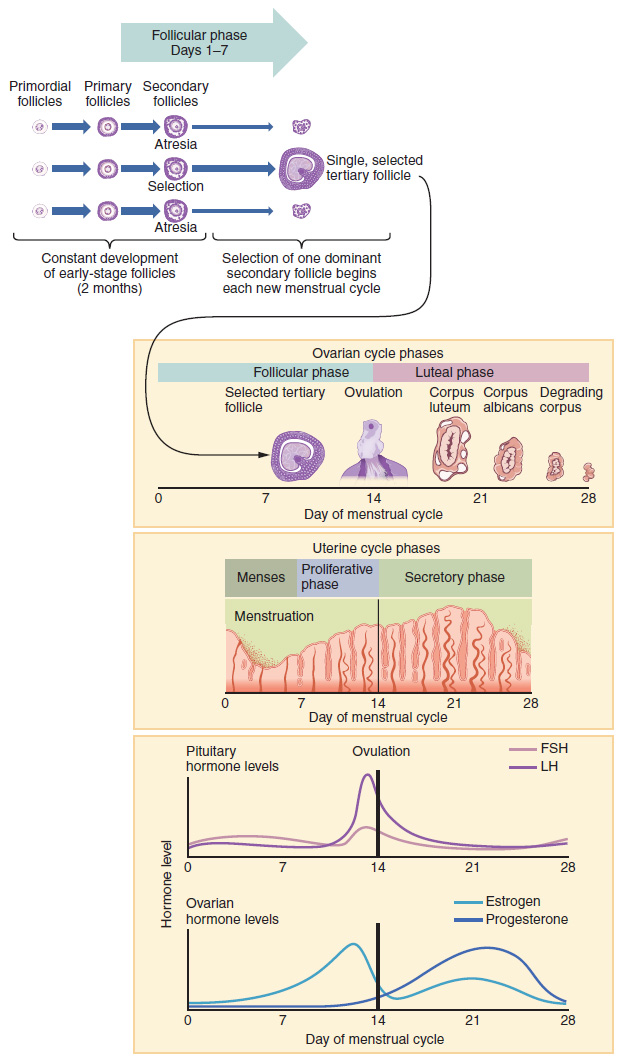

In the first half of the cycle, levels of estrogen start to rise. Estrogen plays an important role bone health and supports growth and thickening in the lining of the uterus. This endometrial lining will nourish the embryo if a pregnancy occurs. At the same time the lining of the womb is growing, an ovum will mature in one of the ovaries. At about day 14 of an average 28-day cycle, the egg leaves the ovary. This is called ovulation.

After the egg has left the ovary, it travels through the fallopian tube to the uterus. Hormone levels rise and help prepare the uterine lining for pregnancy. A woman is most likely to get pregnant during the 3 days before or on the day of ovulation. Keep in mind, women with cycles that are shorter or longer than average may ovulate before or after day 14.

A woman becomes pregnant if the egg is fertilized by a man’s sperm cell and attaches to the uterine wall. If the egg is not fertilized, hormone levels drop the thickened lining of the uterus is shed during the menstrual period.

The Menstrual Cycle

- Day 1 starts with the first day of a period. This occurs after hormone levels drop at the end of the previous cycle, signaling blood and tissues lining the uterus to break down and shed from the body. Bleeding lasts about 5 days.

- Usually by Day 7, bleeding has stopped. Leading up to this time, hormones cause fluid filled pockets called follicles to develop on the ovaries. Each follicle contains an egg.

- Between Day 7 and 14, one follicle will continue to develop and reach maturity. The lining of the uterus starts to thicken, waiting for a fertilized egg to implant. The lining is rich in blood and nutrients.

- Around Day 14 (in a 28-day cycle), hormones cause the mature follicle to burst and release an egg from the ovary, a process called ovulation.

- Over the next few days, the egg travels down the fallopian tube towards the uterus. If a sperm unites with the egg, the fertilized egg will continue down the fallopian tube and attach to the lining of the uterus.

- If the egg is not fertilized, hormone levels will drop around Day 25. This signals the next menstrual cycle to begin. The egg will be shed with the next period.

Female Reproductive Physiology – Sexual Response Cycle and Fertility

Let us consider a research-based paradigm developed by Masters and Johnson (1966) which they called the sexual response cycle. The sexual response cycle is a model that outlines the three phases most people experience when they engage in sexual intercourse: excitement, plateau, and then orgasm. Masters and Johnson were quick to point out that each individual has a unique and varied sexual response, so much so, that no two sexual encounters would be expected to be perfectly identical between the same people. Nevertheless, these three phases are very common among most people.

As sexual intercourse begins both males and females pass through three phases. Excitement phase is when blood flows to the pelvis bringing, more lymphatic fluid and plasma to the region. Because of hormonal and psychological stimuli there is generally swelling in sexual anatomy such as the penis, vaginal walls and clitoris. While this is happening, the plateau phase begins which is when more hormones are released, moisture increases, heart rate increases, intensity of sensory perception increases (touch, smell, sight, hearing, and taste). In the orgasm phase an electrical build up of energy is released that is associated with a rhythmic contraction of the pelvic floor muscles, the urinary and anal sphincters, and of various glands for males. This is called an orgasm. After the orgasm finishes, resolution eventually allows sexual anatomy to return to pre-excitement conditions.

Sexual response in a female would typically follow a pattern similar to this one:

- Excitement phase: Blood and lymphatic fluids increase swelling inside the vagina. Hormones are secreted which lead to a mild uterine contractions which raise the uterus away from the pubic bone. The labia swell and the clitoris becomes hard. The vaginal tissues secrete moisture and the vagina itself lengthens and expands slightly inward.

- Plateau phase: Begins as excitement continues, causing the labia and clitoris to become fully swollen, and the uterus to become elevated. The vagina is lengthened into the body, and, just before orgasm, lubrication ceases.

- Orgasm: The pelvis of the female experiences a series of contractions which occur every 8/10ths of second and can number anywhere from 1-20 or more in the sequence. The contractions include anal and urinary sphincter muscles, smooth muscles in the inward portion of the vagina, and the puboccocceygeus muscles. Further, an electrical sensation surges from the clitoris radiating throughout the body and stimulates the pleasure centers of the brain and a release of the hormone called Oxytocin (the “boding hormone”). When the orgasm ends, the body eventually returns to its pre-excitement state. In general, females have the capacity to experience more contractions over a longer period of time than do males.

Females have been found to have much more capacity for sexual intercourse than males. This means females can have more sexual intercourse, more often, and with more orgasms than can the average male.

The Sexual Experience

Even though the physiological component of sexuality is common between sexes, the anatomical male and female sex drives may not be identical. Studies consistently show that sexual desire for women is more sensitive to the context (meaningful or intimate connection) and the social and cultural environment (quality of relationships, stresses of the day, etc.). This is not surprising given the potential long term “cost” of a sexual encounter for a female. While a male (biologically) always has the opportunity to walk away from a sexual encounter without consequence of pregnancy and/or child rearing, a female does not.

Female Anatomical and Physiological Dysfunction

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID)

Endometriosis

Yeast Infection (Vaginal Candidiasis)

A yeast infection is a fungal infection that may cause irritation of the vulva and discharge from the vagina. Yeast infections are fairly common in women affecting approximately 75% of women at some time in their life and easily treated.

PMS

Premenstrual syndrome is a group of symptoms that cause physical and emotional effects between ovulation and a period. The intensity of symptoms varies from mild in some women to debilitating in others.

PCOS/Ovarian cysts

Ovarian cysts are fluid-filled sacs in or on an ovary. Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a hormonal disorder that may cause numerous cyst to develop on the ovaries (potentially) impacting ovulation. Women with PCOS may have infrequent or prolonged menstrual periods or excess male hormone levels.

Fibroid tumors

Fibroids are abnormal growths that develop in or on the muscle wall of a woman’s uterus. These tumors can become quite large and cause abdominal pain and/or infertility.

Check for Understanding

- Will the resources available to an individual when learning about sexual health affect the choices that person makes regarding their own sexual health?

- What is one possible reason for the preponderance of evidence showing the importance of connection and context in the female sexual experience?

- What types of dysfunction may impact female sex organs? What can be done to reduce risk, treat or manage these conditions?