7 Labor and Childbirth

OpenStax

- identify various stages of labor

- describe components of APGAR score and use in newborn evaluation

- describe various options available in maternal and infant care during and after delivery

- discuss pros and cons of home birth

- discuss pros and cons of hospital birth

- identify

Physiology of Labor

Childbirth typically occurs within a week of a woman’s due date, unless the woman is pregnant with more than one fetus, which usually causes her to go into labor early. As a pregnancy progresses into its final weeks, several physiological changes occur in response to hormones that trigger labor.

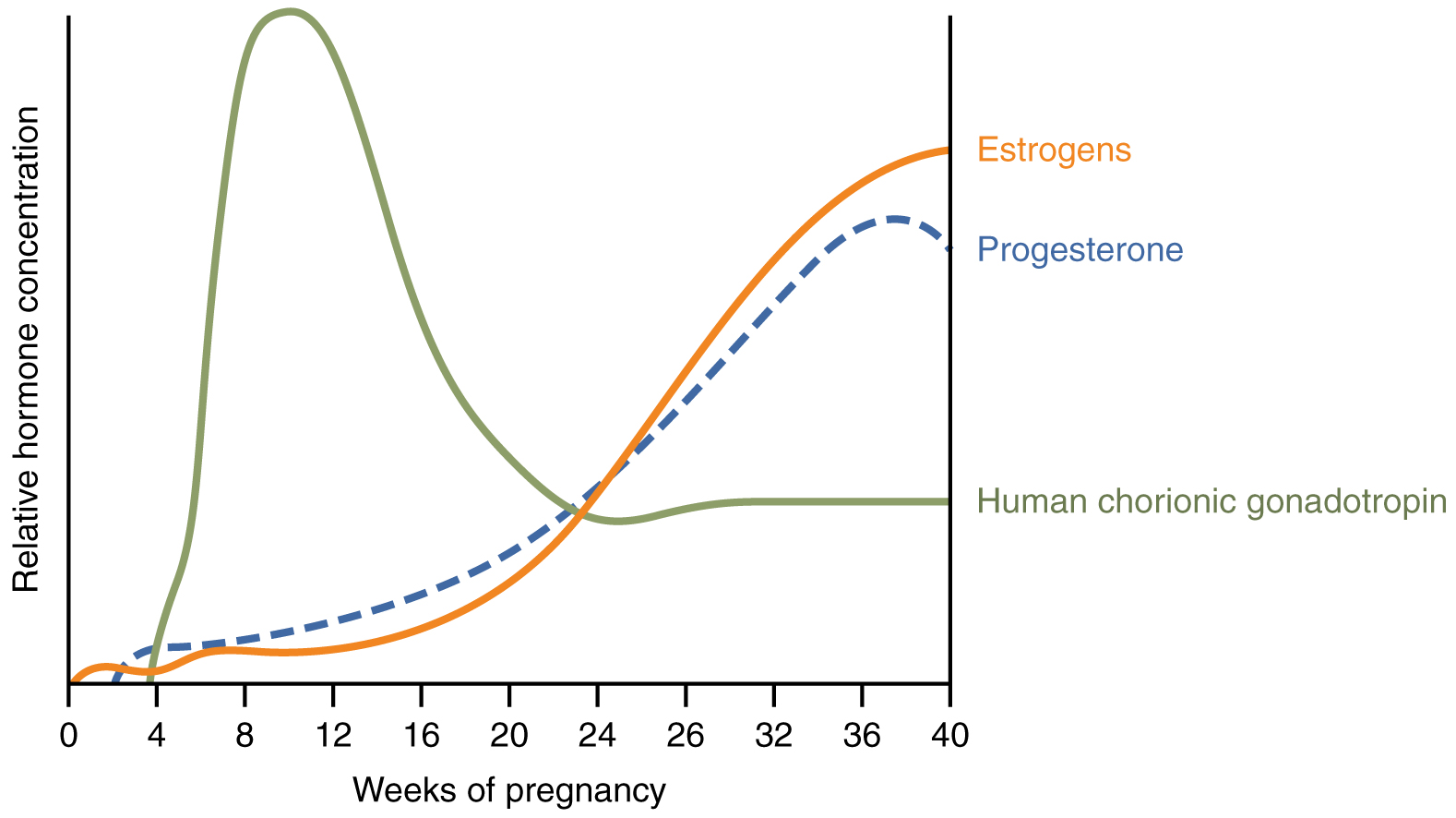

Progesterone inhibits uterine contractions throughout the first several months of pregnancy. As the pregnancy enters its seventh month, progesterone levels plateau and then drop. Estrogen levels, however, continue to rise (Figure 3). The increasing ratio of estrogen to progesterone makes the the uterine muscle (myometrium) more sensitive to stimuli that promote contractions (because progesterone no longer inhibits them). Some women may feel the result of the decreasing levels of progesterone in late pregnancy as weak and irregular Braxton-Hicks contractions, also called false labor. These contractions can often be relieved with rest or hydration.

A common sign that labor will be soon is the so-called “bloody show.” During pregnancy, a plug of mucus accumulates in the cervical canal, blocking the entrance to the uterus. Approximately 1–2 days prior to the onset of true labor, this plug loosens and is expelled, along with a small amount of blood.

Meanwhile, the pituitary gland has been boosting its secretion of oxytocin, a hormone that stimulates the contractions of labor. At the same time, the muscles of the uterus increase sensitivity to oxytocin. Like oxytocin, prostaglandins (chemicals that induce labor) also enhance uterine contractile strength. Given the importance of oxytocin and prostaglandins to the initiation and maintenance of labor, it is not surprising that, when a pregnancy is not progressing to labor and needs to be induced, a pharmaceutical version of these compounds (called pitocin) is administered by intravenous drip.

Finally, stretching of the myometrium and cervix by a full-term fetus in the vertex (head-down) position is regarded as a stimulant to uterine contractions. The sum of these changes initiates the regular contractions known as true labor, which become more powerful and more frequent with time. The pain of labor is attributed to myometrial hypoxia during uterine contractions.

Stages of Childbirth

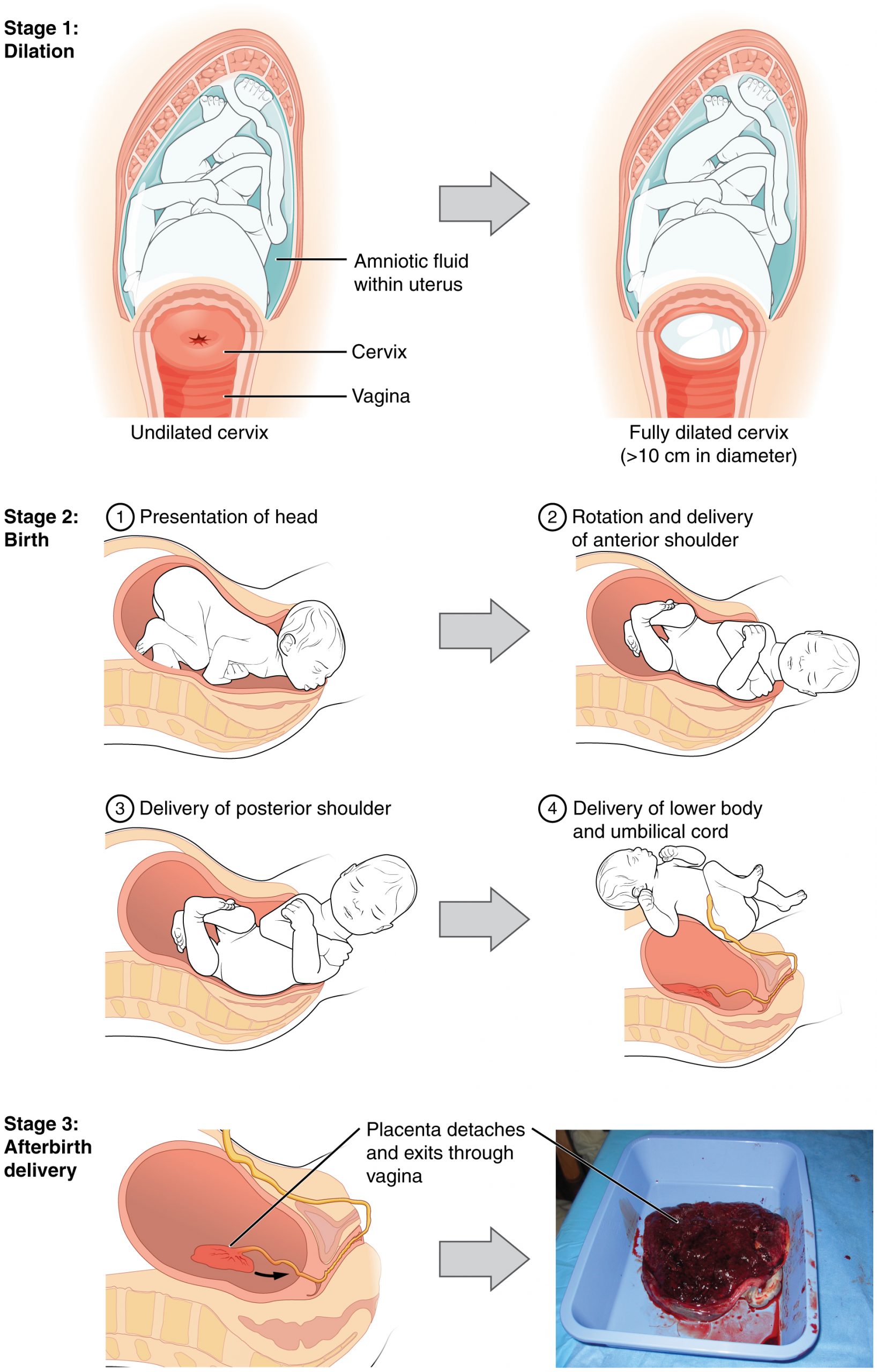

The process of childbirth can be divided into three stages: cervical dilation, expulsion of the newborn, and afterbirth (Figure 4).

Cervical Dilation

For vaginal birth to occur, the cervix must dilate fully to 10 cm in diameter—wide enough to deliver the newborn’s head. The dilation stage is the longest stage of labor and typically takes 6–12 hours. However, it varies widely and may take minutes, hours, or days, depending in part on whether the mother has given birth before; in each subsequent labor, this stage tends to be shorter.

True labor progresses in a positive feedback loop in which uterine contractions stretch the cervix, causing it to dilate and efface, or become thinner. Cervical stretching induces reflexive uterine contractions that dilate and efface the cervix further. In addition, cervical dilation boosts oxytocin secretion from the pituitary, which in turn triggers more powerful uterine contractions. When labor begins, uterine contractions may occur only every 3–30 minutes and last only 20–40 seconds; however, by the end of this stage, contractions may occur as frequently as every 1.5–2 minutes and last for a full minute.

Each contraction sharply reduces oxygenated blood flow to the fetus. For this reason, it is critical that a period of relaxation occur after each contraction. Fetal distress, measured as a sustained decrease or increase in the fetal heart rate, can result from severe contractions that are too powerful or lengthy for oxygenated blood to be restored to the fetus. Such a situation can be cause for an emergency birth with vacuum, forceps, or surgically by Caesarian section.

The amniotic membranes rupture before the onset of labor in about 12 percent of women; they typically rupture at the end of the dilation stage in response to excessive pressure from the fetal head entering the birth canal.

Expulsion Stage

The expulsion stage begins when the fetal head enters the birth canal and ends with birth of the newborn. It typically takes up to 2 hours, but it can last longer or be completed in minutes, depending in part on the orientation of the fetus. The vertex presentation is the most common presentation and is associated with the greatest ease of vaginal birth. The fetus faces the maternal spine and the smallest part of the head (the back of top-back of the head) exits the birth canal first.

In fewer than 5 percent of births, the infant is oriented in the breech presentation, or buttocks down. In a complete breech, both legs are crossed and oriented downward. In a frank breech presentation, the legs are oriented upward. Before the 1960s, it was common for breech presentations to be delivered vaginally. Today, most breech births are accomplished by Caesarian section.

Vaginal birth is associated with significant stretching of the vaginal canal, the cervix, and the perineum. Until recent decades, it was routine procedure for an obstetrician to numb the perineum and perform an episiotomy, an incision in the posterior vaginal wall and perineum. The perineum is now more commonly allowed to tear on its own during birth. Both an episiotomy and a perineal tear need to be sutured shortly after birth to ensure optimal healing. Although suturing the jagged edges of a perineal tear may be more difficult than suturing an episiotomy, tears heal more quickly, are less painful, and are associated with less damage to the muscles around the vagina and rectum.

Upon birth of the newborn’s head, an obstetrician will aspirate mucus from the mouth and nose before the newborn’s first breath. Once the head is birthed, the rest of the body usually follows quickly. The umbilical cord is then double-clamped, and a cut is made between the clamps. This completes the second stage of childbirth.

Afterbirth

The delivery of the placenta and associated membranes, commonly referred to as the afterbirth, marks the final stage of childbirth. After expulsion of the newborn, the myometrium continues to contract. This movement shears the placenta from the back of the uterine wall. It is then easily delivered through the vagina. Continued uterine contractions then reduce blood loss from the site of the placenta. Delivery of the placenta marks the beginning of the postpartum period—the period of approximately 6 weeks immediately following childbirth during which the mother’s body gradually returns to a non-pregnant state. If the placenta does not birth spontaneously within approximately 30 minutes, it is considered retained, and the obstetrician may attempt manual removal. If this is not successful, surgery may be required.

It is important that the obstetrician examines the expelled placenta and fetal membranes to ensure that they are intact. If fragments of the placenta remain in the uterus, they can cause postpartum hemorrhage. Uterine contractions continue for several hours after birth to return the uterus to its pre-pregnancy size in a process called involution, which also allows the mother’s abdominal organs to return to their pre-pregnancy locations. Breastfeeding facilitates this process.

Caesarian Section

Cesarean delivery (C-section) is a surgical procedure used to deliver a baby through an incision in the abdomen (and uterus). A C-section might be scheduled ahead of a woman develops complications during pregnancy that may require this procedure for the health and safety of mom and/or baby.

Your health care provider might recommend a C-section if:

- Labor is not progressing – one of the most common reasons for a C-section. Stalled labor might occur if the cervix is not dilating enough to allow for passage of the baby.

- Baby is distress – concerned about changes in baby’s heartbeat or other vital signs.

- Baby is in an abnormal position – safest way to deliver the baby if his or her feet or buttocks enter the birth canal first (breech) or the baby is positioned side or shoulder first (transverse).

- Carrying multiples – carrying twins and the leading baby is in an abnormal position (or triplets).

- Placenta previa – placenta covers the opening of the cervix

- Umbilical cord prolapse – a loop of umbilical cord slips through the cervix ahead of the baby.

- Health concern – mom has a severe health problem, such as a heart or brain condition or active genital herpes infection at the time of labor.

- Mechanical obstruction – large fibroid obstructing the birth canal, a severely displaced pelvic fracture or your baby has a condition that can cause the head to be unusually large.

- Previous C-section – depending on the type of incision and other factors, it’s often possible to attempt a VBAC (vaginal birth after caesarian). However, your health care provider might recommend a repeat C-section.

Some women request C-sections with their first baby to avoid labor or other possible complications of vaginal birth, or the convenience of a planned delivery. However, this is discouraged because women who have multiple C-sections are at increased risk of placental problems as well as heavy bleeding, which might require surgical removal of the uterus (hysterectomy). Babies born vie C-section usually require more intervention to begin breathing on their own after birth.

Homeostasis in the Newborn: Apgar Score

In the minutes following birth, a newborn must undergo dramatic systemic changes to be able to survive outside the womb. An obstetrician, midwife, or nurse can estimate how well a newborn is doing by obtaining an Apgar score. The Apgar score was introduced in 1952 by the anesthesiologist Dr. Virginia Apgar as a method to assess the effects on the newborn of anesthesia given to the laboring mother. Healthcare providers now use it to assess the general wellbeing of the newborn, whether or not analgesics or anesthetics were used.

Five criteria—skin color, heart rate, reflex, muscle tone, and respiration—are assessed, and each criterion is assigned a score of 0, 1, or 2. Scores are taken at 1 minute after birth and again at 5 minutes after birth. Each time that scores are taken, the five scores are added together. High scores (out of a possible 10) indicate the baby has made the transition from the womb well, whereas lower scores indicate that the baby may be in distress.

The technique for determining an Apgar score is quick and easy, painless for the newborn, and does not require any instruments except for a stethoscope. A convenient way to remember the five scoring criteria is to apply the mnemonic APGAR, for “appearance” (skin color), “pulse” (heart rate), “grimace” (reflex), “activity” (muscle tone), and “respiration.”

Of the five Apgar criteria, heart rate and respiration are the most critical. Poor scores for either of these measurements may indicate the need for immediate medical attention to resuscitate or stabilize the newborn. In general, any score lower than 7 at the 5-minute mark indicates that medical assistance may be needed. A total score below 5 indicates an emergency situation. Normally, a newborn will get an intermediate score of 1 for some of the Apgar criteria and will progress to a 2 by the 5-minute assessment. Scores of 8 or above are normal.

Home Birth

When preparing for pregnancy one of the many choices to be made is who will be attending the birth. Doctors or midwives can attend hospital births and a mother may choose to also have a Doula present specifically to support the mother during the birthing process. If the mother and partner would prefer the advantages of a home birth these can be attended by certified midwifes and Doulas. The following article give more information about the pros and cons of choosing a home birth.

Pros and Cons of Home Birth (read article or listen to 4 minute audio)

Pregnancy Loss

Unfortunately, not all pregnancies go as planned. complications may arise that result in miscarriage (loss of a baby before the age of viability) or stillbirth (loss of a baby after the age of viability). There are many different potential causes of miscarriages or stillbirth and as many different emotional reactions and grieving processes for a family involved.

Check for Understanding

- What are the stages of labor and what happens to mom and baby in each stage?

- What birthing options are available to a mother and partner? Why might a person choose one of these options over another?

- What are the components of and APGAR score and how is is used?

- What are the potential physical causes and emotional impacts of pregnancy or infant loss?

- Why is miscarriage or infant loss not talked about the way other forms of loss are?