Strategies for Getting Started

Andy Gurevich

Getting Going

How do you start writing a draft? There isn’t just one right way to begin writing. Some people dive right in, writing in complete sentences and paragraphs, while others start with some form of brainstorming or freewriting. Others choose a strategy based on the writing task and how familiar they are with the topic. A writing instructor may want you to try out different methods so that you can figure out what works best for you. You may want to have more than one method in case you get stuck and need to break out of a writing block. Here are some common strategies for getting started (sometimes called invention strategies).

There are several methods that help you generate ideas and see connections between ideas without writing in complete sentences. We can call these methods “brainstorming.” They all have some common rules:

- Write down all of your ideas; don’t eliminate anything until you are done brainstorming.

- Don’t bother with editing at this stage.

- Work as quickly as you can.

- If you get stuck, stop and review your work OR get someone else’s input.

- Each method can work as a solo technique or with others.

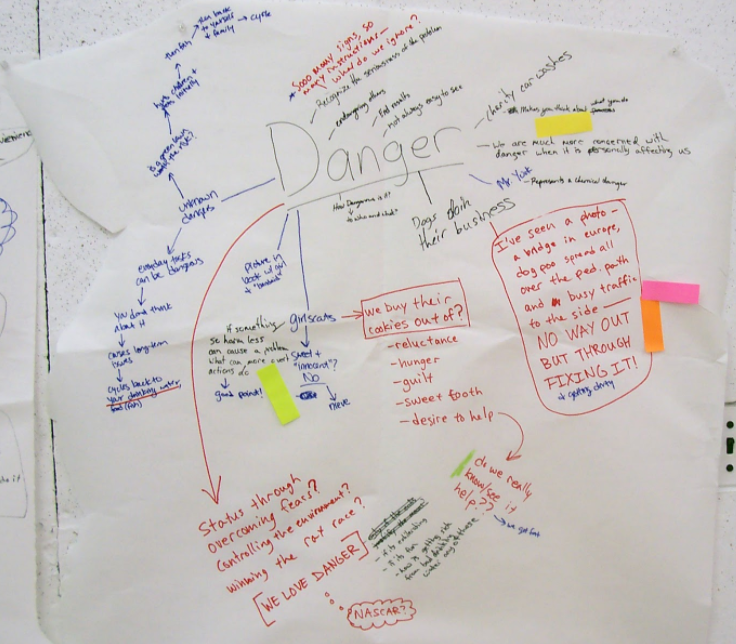

Clustering

A cluster is a method of brainstorming that allows you to draw connections between ideas. This technique is also called a tree diagram, a map, a spider diagram, and probably many other terms.

- To make a cluster, start with a big concept. Write this in the center of a page or screen and circle it.

- Think of ideas that connect to the big concept. Write these around the big concept and draw connecting lines to the big concept.

- As you think of ideas that relate to any of the others, create more connections by writing those ideas around the one idea that connects them and draw connecting lines.

Here’s an example:

Notice that you can use color, larger type, etc., to create organization and emphasis. Remember that your cluster doesn’t need to look like anyone else’s. Create the cluster in the way that makes the most sense to you. Once you have finished the cluster, you can use another technique to generate actual text.

Listing

Listing is just what it sounds like: making a list of ideas. Here are two kinds of lists you might use.

Brainstorm list: Simply make a list of all the ideas related to your topic. Do not censor your ideas; write everything down, knowing you can cross some off later.

Here’s an example:

What I know/don’t know lists: If you know that your topic will require research, you can make two lists. The first will be a list of what you already know about your topic; the second will be a list of what you don’t know and will have to research.

Outlining

Outlining is a useful pre-writing tool when you know your topic well or at least know the areas you want to explore. An outline can be written before you begin to write, and it can range from formal to informal. However, many writers work best from a list of ideas or from freewriting. (Note: A reverse outline can be useful once you have written a draft, during the revision process. For more on reverse outlining, see the “Revising” section.)

Traditional Outline

A traditional outline uses a numbering and indentation scheme to help organize your thoughts. Generally, you begin with your main point, perhaps stated as a thesis (see “Finding the Thesis” in the “Drafting Section”), and place the subtopics, usually the main supports for your thesis/main point, and finally flesh out the details underneath each subtopic. Each subtopic is numbered and has the same level of indentation. Details under each subtopic are given a different style of number or letter and are indented further to the right. It’s expected that each subtopic will merit at least two details. NOTE: Most word-processing applications include outlining capabilities.

Phrase: Some outlines use a phrase for each item.

Sentence: Some outlines, particularly for oral presentations, use a complete sentence for each item.

Paragraph: Rarely, an outline may use a paragraph for each item.

Q&A: Some outlines are organized in a question/answer format.

Here’s an example:

I. Major Idea

a. Supporting Idea

i. Detail

ii. Detail

b. Supporting Idea

i. Detail

ii. Detail

iii. Detail

Rough Outline

A rough outline is less formal than a traditional outline. Working from a list, a brainstorm, or a freewrite, organize the ideas into the order that makes sense to you. You might try color-coding like items and then grouping the items with the same color together. Another method is to print your prewriting, then cut it up into smaller pieces, and finally put the pieces into piles of related items. Tape the like items together, then put the pieces together into a whole list/outline.

Ready to try an outline?

- Watch the YouTube video, “Outlines” from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, to help yourself get started:

Freewriting

Freewriting is a technique that actually generates text, some of which you may eventually use in your final draft. The rules are similar to brainstorming and clustering:

- Write as much as you can, as quickly as you can.

- Don’t edit or cross anything out. (Note: if you must edit as you go, just write the correction and keep moving along. Don’t go for the perfect word, just get the idea on the page.)

- Keep your pen, pencil, or fingers on the keyboard moving.

- You don’t need to stay on topic or write in any order. Feel free to follow tangents.

- If you get stuck, write a repeating phrase until your brain gets tired and gives you something else to write. (Variation: I like to complain at this point, so I write about the fact that I’m stuck, I really hate having to do this, why isn’t it lunch-time already, etc.)

- Freewriting can be used just to get your mind working so that you can write an actual draft. In this case, you can write about whatever you want. Freewriting to generate ideas usually works best when you start with a prompt–an idea or question that gets you started. An example of a writing prompt might be “What do I already know about this topic?” Or “What is the first idea I have about my topic?” If you started with a list or an outline, you can freewrite about each item.

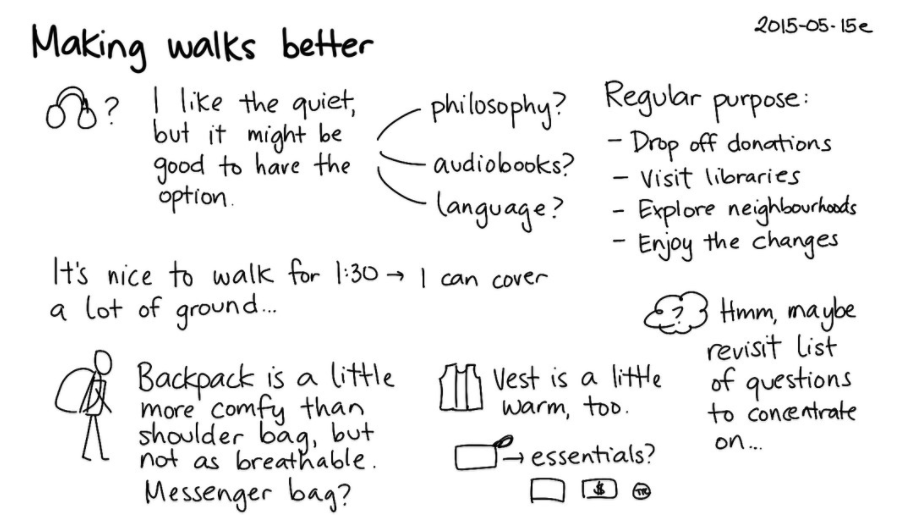

Looping

Looping is a technique built on freewriting. It can help you move within a topic to get all related ideas into writing.

- To begin, start with a freewrite on a topic. Set a timer and write for 5-15 minutes (whatever you think will be enough time to get going but not so much that you will want to stop).

- When the time period ends, read over what you’ve written and circle anything that needs to be fleshed out or that branches into new ideas. Select one of these for your next loop.

- Freewrite again for the same time period, using the idea you selected from the first freewrite.

- Repeat until you feel you have covered the topic or you are out of time.

Asking Questions

To stimulate ideas, you can ask questions that help you generate content. Use some of the examples below or come up with your own.

Problem/Solution: What is the problem that your writing is trying to solve? Who or what is part of the problem? What solutions can you think of? How would each solution be accomplished?

Cause/Effect: What is the reason behind your topic? Why is it an issue? Conversely, what is the effect of your topic? Who will be affected by it?

The set of journalist’s questions is probably the most familiar for writers. Using the journalist’s questions, sometimes called the five W’s, is an effective way to write about the basic information about your topic. Here are the questions:

- Who: Who is involved? Who is affected?

- What: What is happening? What will happen? What should happen?

- Where: Where is it happening?

- When: When is it happening?

- Why/how: Why is this happening? How is it happening?

If you imagine the questions as a cube, and separate why and how into two, you can use that visual image to remember the six questions.

Imagining Your Audience’s Needs

Here are some common audiences for you to consider before you begin drafting an assignment (also see the “Audience” section in the “Determining Audience and Purpose” portion of this text):

Yourself

One purpose for writing is to figure out what you think and believe before you share your ideas with other people. What do you want to say? What do you want to find out? What do you want to decide? Sometimes you will keep this type of writing private, but sometimes you may revise for another audience.

Your Instructor

It may seem obvious as a student that your instructor is part of your audience. Let’s take a moment to consider what expectations your instructor may have. You instructor may expect that

- You have read any assigned material before writing. What do you need to write to show your instructor you have read this material?

- You have understood the assignment given. To show this, pay particular attention to the verbs in the assignment. Are you doing the actions required? If the assignment says “analyze X,” have you done so? Do you understand what it means to analyze? (For more about verbs in assignments, see the Understanding Assignments handout from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Writing Center.)

- If assigned, you have done research for your topic. To show your research, you will want to use summaries, paraphrasing, and quotations from your sources, using appropriate citation. (See the Drafting section for help with summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting, and see the “Crediting and Citing Your Sources” section for help with citations.)

- You will use the assigned academic format, such as MLA (see the appendix titled “Resources for Working with MLA”). You will follow the instructions. Re-read the assignment to make sure you are following each step.

- You will work hard on your assignment and spend time making it as good as possible, including spending considerable time proofreading and editing. Taking these steps shows that you are serious about your work, and that it is important enough for others to read.

Notice that fulfilling these expectations will also help you reach any other possible readers of your work.

Fellow Students

In writing classes, students often read each other’s work and give feedback. To meet the needs of this audience, consider what they know and don’t know about your topic. When you are writing outside of a classroom situation, you might consider an audience of fellow writers or others who are involved in your project, if any.

The “General” Reader

When instructors use the term “general reader,” what do they mean? If you are given an assignment that says your audience is “the general reader,” that usually means that you are expected to write to an audience with at least some college education who is aware of your topic, but not an expert on your topic. Newspapers, for example, write for a general reader, meaning that they expect a variety of people, from various backgrounds, to read the articles. That means you must consider viewpoints and experiences that do not mirror your own. When instructors talk about an academic audience, they usually mean that you must use evidence that is acceptable to a variety of educated people, using academic sources rather than popular sources, and that you will not state opinions without providing proof to support your view. Here are some questions to help you think about your topic:

What would a general reader know about your topic? What wouldn’t they know?

What kinds of evidence and reasons are acceptable to an audience that does not share the same background and beliefs as you?

What kinds of evidence and reason are acceptable in an academic community? Have you used academic sources? Are your sources credible? (For some guidance on finding credible sources see “Finding Quality Texts” in the Information Literacy section.)

A Target Audience

Sometimes you will have the opportunity to write for a specific group of people. For example, if you are writing about a problem in your community, such as the proposed location of a new composting facility, your audience would probably be the people in your community or perhaps local officials who have the power to make the decision about the location. If you are writing an email to your supervisor requesting a change in your work responsibilities, your audience is your supervisor–a specific person. When you know the audience, you can anticipate the kinds of reasoning and evidence that the audience will expect, and you will know what tone and level of formality is appropriate. If you don’t know your audience well, you may need to do some research or at the very least imagine what they are like based on educated guesses.

The Opposing Viewpoint

When you write an argument, one potential audience is the people who disagree with your opinion. To do so effectively, you will need to understand their point of view and their objections to yours. Consider writing out what the opposing viewpoints are and what kinds of information would someone with the opposing view need from you in order to change their mind?

(adapted, in part, from The Word on College Reading and Writing by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear. This OER text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.)