Prewriting

Audience, Brainstorming, Tone, Style, and Purpose

Andy Gurevich

Audience

by Burns Library, Boston College is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Each time you communicate, in writing or otherwise, you consider whom you’re communicating with and why, whether you’re conscious of this or not. Think about it: if you’re asking your best friend for a favor, aren’t you going to ask differently than if you were asking your boss for a raise? You already have a great instinct for knowing how to shape language around the people you are addressing and what your goal is. So how can you use this instinct when writing for your college classes?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A roaring political rally, a studio audience, dancing concert goers—these are all examples of different types of audiences, but an audience for your writing is a bit different. All audiences have a job to do: they are consumers of information or experiences. So when you set out to write, deciding who your audience is, is an important first step.

What is the Difference between an Audience and a Reader?

Great question! It’s as simple as this: your audience is the person or group whom you intend to reach with your writing. A reader is just someone who gets their hands on your beautiful words. The reader might be the person you have in mind as you write, the audience you’re trying to reach, but they might be some random person you’ve never thought of a day in your life. You can’t always know much about random readers, but you should have some understanding of who your audience is. It’s the audience that you want to focus on as you shape your message.

Isn’t My Instructor Always My Audience?

Sometimes your instructor will be your intended audience, and your purpose will be to demonstrate your learning about a particular topic to earn credit on an assignment. Other times, even in your college classes, your intended audience will be a person or group outside of the instructor or your peers. This could be someone who has a personal interest in or need to read about your topic but who may never actually read your work unless it finds a place to be published like a blog or website. Understanding who your intended audience is will help you shape your writing.

Here are some questions you might think about as you’re deciding what to write about and how to shape your message:

- What do I know about my audience? (age, gender, interests, biases, or concerns; Do they have an opinion already? Do they have a stake in the topic?)

- What do they know about my topic? (What does this audience not know about the topic? What do they need to know?)

- What details might affect the way this audience thinks about my topic? (How will facts, statistics, personal stories, examples, definitions, or other types of evidence affect this audience? What kind of effect are you going for?)

Purpose

by jon collier is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Often, you’ll know your purpose at the exact moment you know your audience because they’re generally a package deal:

- I need to write a letter to my landlord explaining why my rent is late so she won’t be upset. (Audience = landlord; Purpose = explaining/keeping her happy)

- I want to write a proposal for my work team to persuade them to change our schedule. (Audience = work team; Purpose = persuading/to get the schedule changed)

- I have to write a research paper for my environmental science instructor comparing solar to wind power. (Audience = instructor; Purpose = analyzing/showing that you understand these two power sources)

How Do I Know What My Purpose Is?

Sometimes your instructor will give you a purpose like in the third example above, but other times, especially out in the world, your purpose will depend on what effect you want your writing to have on your audience. What is the goal of your writing? What do you hope for your audience to think, feel, or do after reading it? Here are a few possibilities:

- Persuade/inspire them to act or think about an issue from your point of view.

- Challenge them/make them question their thinking or behavior.

- Argue for or against something they believe or do/change their minds or behavior.

- Inform/teach them about a topic they don’t know much about.

- Connect with them emotionally/help them feel understood.

Appealing to Your Audience

via Wikimedia Commons

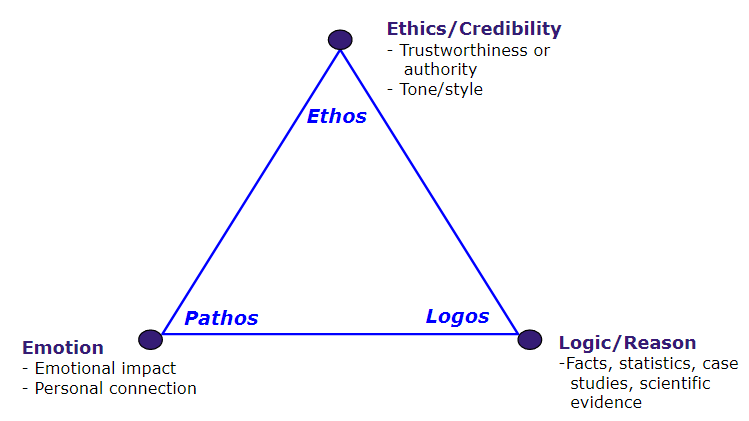

Once you know who your intended audience is and what your purpose is for writing, you can make specific decisions about how to shape your message. No matter what, you want your audience to stick around long enough to read your whole piece. How do you manage this magic trick? Easy. You appeal to them. You get to know what sparks their interest, what makes them curious, and what makes them feel understood. The one and only Aristotle provided us with three ways to appeal to an audience, and they’re called logos, pathos, and ethos. You’ll learn more about each appeal in the discussion below, but the relationship between these three appeals is also often called the rhetorical triangle, and in diagram form, it looks like this:

Pathos

Latin for emotion, pathos is the fastest way to get your audience’s attention. People tend to have emotional responses before their brains kick in and tell them to knock it off. Be careful though. Too much pathos can make your audience feel emotionally manipulated or angry because they’re also looking for the facts to support whatever emotional claims you might be making so they know they can trust you.

Logos

Latin for logic, logos is where those facts come in. Your audience will question the validity of your claims; the opinions you share in your writing need to be supported using science, statistics, expert perspective, and other types of logic. However, if you only rely on logos, your writing might become dry and boring, so even this should be balanced with other appeals.

Ethos

Latin for ethics, ethos is what you do to prove to your audience that you can be trusted, that you are a credible source of information. (See logos.) It’s also what you do to assure them that they are good people who want to do the right thing. This is especially important when writing an argument to an audience who disagrees with you. It’s much easier to encourage a disagreeable audience to listen to your point of view if you have convinced them that you respect their opinion and that you have established credibility through the use of logos and pathos, which show that you know the topic on an intellectual and personal level.

- View the video: The Rhetorical Triangle and Rhetorical Appeals that goes into more detail about the three appeals and how Aristotle used the rhetorical triangle to illustrate the relationship between the appeals and the audience.

- For more on appealing to your audience, also see Imagining Your Audience’s Needs, in the “Prewriting: Generating Ideas” section of the text.

Exercises

Ready to practice writing for specific audiences? Below you’ll find eight pictures of people with some information about each person included. Choose two people to write letters to. The purpose of your letter writing is to ask these people to give you $100. Please follow these two rules: you cannot say you will pay the money back, because you won’t. You’re not asking for a loan. Also, you cannot lie or exaggerate about why you need the $100. Think of a real reason. We could all use $100, after all! With these parameters in mind, how will you manage to persuade these people to give you the money?

Ready to practice writing for specific audiences? Below you’ll find eight pictures of people with some information about each person included. Choose two people to write letters to. The purpose of your letter writing is to ask these people to give you $100. Please follow these two rules: you cannot say you will pay the money back, because you won’t. You’re not asking for a loan. Also, you cannot lie or exaggerate about why you need the $100. Think of a real reason. We could all use $100, after all! With these parameters in mind, how will you manage to persuade these people to give you the money?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

| Jeremiah is the director of a non-profit organization that helps homeless youth get an education. He is thirty-three and is married with three small children. In his free time, Jeremiah enjoys practicing karate, hiking with his wife and kids, and reading historical fiction. |

|

| Deborah is a forty-year-old professional violinist who plays full time in the Portland Symphony Orchestra. She considers the orchestra to be her family. She isn’t married and doesn’t have children. When she’s not practicing her instrument, Deborah enjoys painting with acrylics and cross-country skiing. |

|

| Ronaldo is a twenty-seven-year-old middle school biology teacher who also coaches track and field. He and his wife have just adopted two children from Haiti, so most of Ronaldo’s free time is spent reading parenting books and being the best father he can be. |

|

| Grace is a twenty-year-old Marine in a family of Marines. She met her partner Jane during basic training, and they are planning to get married after they’ve both finished college. Grace’s hobbies include kickboxing, wakeboarding, and training her dog, Boss. |

|

| Henry is a retired CEO for a fishing rod manufacturing company. At the age of eighty-four, he still enjoys fly fishing all over the Pacific Northwest. He is recently widowed and has seven grandchildren who go fishing with him regularly. |

|

| Sophia is a dancer, dance teacher, and new mother. She just turned thirty and loves to travel with her husband. Her goal is to see every continent (except for Antarctica) before the age of forty. So far, she’s been to North and South America, Africa, and Asia. |

|

| Larry is a foreman for a construction company that builds skyscrapers and other types of office buildings. He’s fifty-seven and has saved enough to be able to retire by the age of sixty, when he hopes to move to the mountains and build a log cabin with his partner David. |

|

| Michelle is a pediatric doctor who specializes in childhood leukemia. She is thirty-five and newly married to an ER doctor. They support each other’s research projects and other professional goals. They don’t want children, feeling that their work is their primary life focus. |

|

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Figure 1: “Listening at a conference” by BMA is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Figure 2: “Barka Fabianova” by Cordella Hagmann is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Figure 3: “Slongood” by bidding is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Figure 4: “Expert Infantry” by DM-ST-86-05538 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Figure 5: “The Grandfather” by Xavez is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Figure 6: “New Mother New Baby” by Satoshi Ohki is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Figure 7: “Construction Worker” by Sascha Kohlmann is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Figure 8: “Waiting to Speak” by The BMA is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Tone, Voice, and Point of View

Yo! Wassup?

Hey, how you doin’?

Hello, how are you today?

Which of the above greetings sounds most formal? Which sounds the most informal? What causes the change in tone?

Your voice can’t actually be heard when you write, but it can be conveyed through the words you choose, the order you place them in, and the point of view from which you write. When you decide to write something for a specific audience, you often know instinctively what tone of voice will be most appropriate for that audience: serious, professional, funny, friendly, neutral, etc.

For a discussion of analyzing an author’s point of view when reading a text, see Point of View in the “Writing about Texts” section.

What is point of view, and how do I know which one to use?

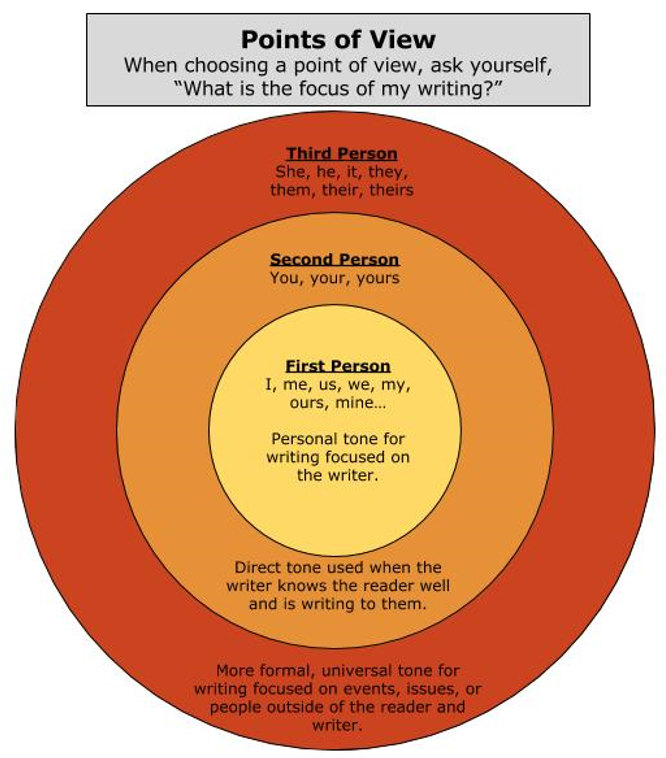

Point of view can be tricky, so this is a good question. Point of view is the perspective from which you’re writing, and it dictates what your focus is. Consider the following examples:

- I love watching the leaves change in the fall. (First person point of view)

- You will love watching the leaves change color. (Second person)

- The leaves in fall turn many vibrant colors. (Third person)

Which of the above sentences focuses most clearly on the leaves? Third person, right? The first person sentence focuses on what “I” love and the second person sentence focuses on what “you” will love.

- First person uses the following pronouns: I, me, my, us, we, myself, our, ours … any words that include the speaker/writer turn the sentence into first person.

- Second person uses any form of the word “you,” which has the effect of addressing the reader.

- Third person uses pronouns like he, she, it, they, them … any words that direct the reader to a person or thing that is not the writer or reader turn the sentence into third person.

That’s a lot to think about. When is it okay to use each of these points of view?

Using the pronoun “I.”

There is a longstanding tradition in composition courses that suggests students should avoid using the personal pronoun “I” in their writing. This needs to be explained in order to make sense in the modern world and there are cultural considerations to explore here, as well. The issue is not to adhere to some antiquated “rule” about the first person pronoun. It has more to do with the proper use of authority and point of view. In an essay, sometimes it will be appropriate for the student to rely on their own thoughts, experiences, opinions and worldviews to make a point. In these cases, it has become more acceptable to use the first person personal pronoun than the older, more awkward constructions such as “this student believes” or “according to the writer…” If you are speaking from the center of your own experience and authority, and it is appropriate to do so, then use the pronoun “I.” But frequently in essays, we need to move beyond our own ideas, our own opinions, our own experiences, and engage the thoughts and worldviews of others. In these cases, it is less important to center ourselves in the writing and focus more on the presence of the voices and ideas of others. In these cases, we would naturally move away from a focus on “I” and move into a larger engagement with the other. Let your topic, assignment, and specific thesis be your guide here. And when in doubt, ask your instructor.

Many of your college instructors will ask you to write in third person only and will want you to avoid first or second person. Why do you think that is? One important reason is that third person point of view focuses on a person or topic outside yourself or the reader, making it the most professional, academic, and objective way to write. The goal of third person point of view is to remove personal, subjective bias from your writing, at least in theory. Most of the writing you will do in college will require you to focus on ideas, people, and issues outside yourself, so third person will be the most appropriate. This point of view also helps your readers stay focused on the topic instead of thinking about you or themselves.

The best answer to your question is that the point of view you choose to write in will depend on your audience and purpose. If your goal is to relate to your audience in a personal way about a topic that you have experience with, then it may be appropriate to use first person point of view to share your experience and connect with your audience.

The least commonly used point of view is second person, especially in academic writing, because most of the time you will not know your audience well enough to write directly to them. The exception is if you’re writing a letter or directing your writing to a very specific group whom you know well. (Notice that I’m using second person in this paragraph to directly address you. I feel okay about doing this because I want you to do specific things, and I have a pretty good idea who my audience is: reading and writing students.) The danger of using second person is that this point of view can implicate readers in your topic when you don’t mean to do that. If you’re talking about crime rates in your city, and you write something like, “When you break into someone’s house, this affects their property value,” you are literally saying that the reader breaks into people’s houses. Of course, that’s not what you mean. You didn’t intend to implicate the readers this way, but that’s one possible consequence of using second person. In other words, you might accidentally say that readers have done something that they haven’t or know, feel, or believe something that they don’t.

Even when you intend to use third person in an academic essay, it’s fine in a rough draft to write “I think that” or “I believe” and then to delete these phrases in the final draft. This is especially true for the thesis statement. You want to eliminate the first person from the final draft because it moves the focus—the subject and verb of the sentence—to the writer rather than the main point. That weakens the point because it focuses on the least important aspect of the sentence and also because it sounds like a disclaimer. I might say “I think” because I’m not sure, or “I believe” because I want to stress the point that this is only my opinion. Of course, it’s okay to use a disclaimer if you really mean to do so, and it’s also fine to use first person to render personal experience or give an anecdote.

Does anything else affect the tone of my writing?

Yes! Many times writers are so focused on the ideas they want to convey that they forget the importance of something they may never think about: sentence variety. The length of your sentences matters. If you start every sentence with the same words, readers may get bored. If all of your sentences are short and choppy, your writing may sound unsophisticated or rushed. Some short sentences are nice though. They help readers’ brains catch up. This is a lot to think about while you’re writing your first draft though, so I recommend saving this concern for your second or third draft.

Visit the Purdue OWL page, “Strategies for Variation” for some examples of sentence variety and exercises that will improve your sentence variety superpowers.

Selecting and Narrowing a Topic

is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

When you need to write something longer than a text or an email, whether it’s a class assignment, a report for work, or a personal writing task, there’s work to be done before you dive in and begin writing. This phase is sometimes called prewriting (even though some types of prewriting involve actual writing).

Note that even though instructors may describe a writing process as having steps that seem to go in order, writers usually skip back and forth between those steps as they work toward a final draft. While you’re in the early stage of prewriting, you might use freewriting (a technique for generating text that you’ll learn more about in the section titled “Strategies for Getting Started“) but then use that technique again after revising your first draft. When instructors describe writing as “recursive,” this process is what they are talking about. The techniques described for prewriting may come in handy later in your own writing process.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

If you’re working on a class assignment, you may get to select your own topic or a topic may be assigned to you.

If you get to choose your topic, be sure that you understand the kinds of topics that will fit the assignment. For example, if your instructor asks you to write an argument about a local problem in your community, you wouldn’t choose to write about the national debt–that’s not a local problem, but a national one. You might try some of the techniques in this resource, like freewriting, listing, or clustering, to discover topics you are interested in. You might use your library’s online databases to search for interesting topics, especially databases that give pros and cons for current issues.

But even if the instructor assigns the topic, you can find ways to make it your own.

Types of Assignments from Instructors

Most of the time, instructors give specific assignments that relate to the course and perhaps to assigned readings or discussions from class. When you are given a specific topic, be sure that you understand what you have been asked to do. Look for the verbs used in the assignment. Here are some common verbs from writing assignments and what they usually mean:

Summarize: If you are asked to write a summary of something you’ve read, you will be giving the main points and the supporting points from the text. A summary usually does not include your personal opinion.

Respond: When you are asked to respond to a text, you can give your opinion in a variety of ways. You might talk about the quality of the text, connections you made with the text, or whether you agree or disagree with the author’s ideas. You may need to incorporate a little bit of summary so that the reader has enough background to understand your response. The summary might be in the form of a single paragraph after your introduction, it might be a few sentences within your introduction, or it might be incorporated in multiple paragraphs in a sentence or two.

Analyze: An analysis breaks something down into parts in order to understand the whole. See discussions of sentence-level analysis and paragraph analysis in the “Writing about Texts” section.

Synthesize: A synthesis combines two or more ideas into a larger whole. For more on synthesis, see “Drawing Conclusions and Synthesizing New Ideas” in the “Writing about Texts” section.

Compare and contrast: When you are asked to compare and contrast (or sometimes the instructor will just say compare, but mean both), you will be looking at two items and stating how they are alike and how they are different.

Reflect: A reflection asks you to deeply consider something, often on a personal basis. For example, you might be asked to write a personal reflection about your own writing or about your progress during a course. Or you might be asked to reflect on how a particular issue affects you.

Other terms: There are many possible verbs that you might find in an assignment. If you are unsure what the assignment calls for, be sure to ask your instructor.

Picking Your Own Topic When One Isn’t Assigned

For some assignments, you may be able to write about a topic that is personally significant to you. Being able to write about a topic like this can improve your motivation. Be wary, though, of just writing opinion without backing up your ideas with reasons and evidence that your readers will find convincing. If you want to write about a deeply personal topic, be sure that you are willing to share that with others and also consider whether or not your readers want to know that information about you.

One way to narrow your topic is to decide what you DON’T want to write about. What ideas or subtopics could you eliminate?

Using Preliminary Research

Another way to narrow your topic is to do some preliminary research–not the kind of research you would include in an essay, but rather quick online research to inform yourself about the topic. This is one example of when it’s okay to use a simple Google search or use Wikipedia. Once you see what other people are writing about your topic, it can help you see areas that are interesting to you, and it can also help you understand what people, in general, agree on and what is still undecided and needs to be further explored.

Check Your Understanding: Preliminary Research

Check Your Understanding: Preliminary Research

Want to try some preliminary research? Try searching for these topics in Google and Wikipedia, for general information.

Search for “gravity hill” in Google.

- How many of the sources on the first page of results are from Wikipedia?

- Where is the gravity hill in South Dakota located?

Search for T. Rex, the band, in Wikipedia.

- What later bands and musicians made explicit references to T. Rex?

- What is the first source listed in the “References” section at the end of the Wikipedia article?

See the Appendix, Results for the “Check Your Understanding” Activities, for answers.

Using Purpose to Determine Topic

You can also use your purpose for writing to define your topic:

Informative: if your purpose in writing is to inform your readers, what are topics that you already know a lot about? What are some interesting topics that you could easily research?

Persuasive: if your purpose is to persuade readers to think a certain way or to take an action, what are some topics that you feel strongly about? What are some topics that are currently under discussion that you could explore and form an opinion on?

Reflective: if your purpose is to reflect on a personal experience or on your learning process, you can explore your knowledge and experience.

Analytical: if your purpose is to analyze something (usually a text of some kind), is there an assigned list or a specific text? If you get to choose, what books, essays, poems, films, songs, etc. have you recently been exposed to that you could analyze?

(adapted, in part, from The Word on College Reading and Writing by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear. This OER text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.)