Efficient Reading Strategies

Andy Gurevich

Read Efficiently

Sit down (in your ideal setting and at your ideal time, if possible) and prepare to read. Do whatever you need to do to minimize distractions during your reading session. (This may include putting your smartphone and other technology in another room.) Have paper and pencil available to take notes.

Read carefully, stopping and rereading sections you don’t quite understand. Be sure to look up words you’re not familiar with. This is important! Most of us are good contextual readers; that is, we can usually figure out what an unfamiliar word means based on the content around it. But in your academic, college-level writing, every word is important, and some words carry enough power to change the meaning of a sentence or to launch it into a whole new level of detail. Also, some words have different meanings in the academic setting than in our more casual everyday lives. When you hit a word you don’t know, stop, make a note in the margin (or on a piece of paper), and look it up. If you find that stopping to look up individual words is too distracting, you can make a list of all the unknown words you run into and then look them all up when you’ve finished reading.

Keep reading until you’re done. Don’t be distracted. If you begin to feel fidgety, stop, get up, and take a five minute break. Then get back to your reading. The more you read, the stronger your habit will grow, and the easier reading will be.

Annotate and Take Notes

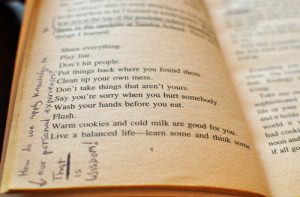

As children, most of us were told never to write in books, but now that you’re a college student, your teachers will tell you just the opposite. Writing in your texts as you read—annotating them—is encouraged! It’s a powerful strategy for engaging with a text and entering a discussion with it. You can jot down questions and ideas as they come to you. You might underline important sections, circle words you don’t understand, and use your own set of symbols to highlight portions that you feel are important. Capturing these ideas as they occur to you is important, for they may play a role in not just understanding the text better but also in your college assignments. If you don’t make notes as you go, today’s great observation will likely become tomorrow’s forgotten detail.

Important note: most college and university bookstores approve of textual annotation and don’t think it decreases a textbook’s value. In other words, you can annotate a college textbook and still sell it back to the bookstore later on if you choose to. Note that I say most—if you have questions about your own school and plan to sell back any textbooks, be sure to ask at the bookstore before you annotate.

If you can’t write on the text itself, you can accomplish almost the same thing by taking notes—either by hand (on paper) or e-notes. You might also choose to use sticky notes to capture your ideas—these can be stuck to specific pages for later recall. For a strategy that helps you take note of what you see as interesting or important points of a text while also responding to those points with your own ideas, see “Dialectic Note-taking” in the “Writing about Texts” section of this text.

Many students use brightly-colored highlighting pens to mark up texts. These are better than nothing, but in truth, they’re not much help. Using them creates big swaths of eye-popping color in your text, but when you later go back to them, you may not remember why they were highlighted. Writing in the text with a simple pen or pencil is always preferable.

![]() When annotating, choose pencil or ball-point ink rather than gel or permanent marker. Ball point ink is less likely to soak through the page. If using erasable pens, test in an inconspicuous area to make sure they actually erase on that paper.

When annotating, choose pencil or ball-point ink rather than gel or permanent marker. Ball point ink is less likely to soak through the page. If using erasable pens, test in an inconspicuous area to make sure they actually erase on that paper.

What about e-books? Most of them have on-board tools for note-taking as well as providing dictionaries and even encyclopedia access.

Many students also like to keep reading journals. A good way to use these is to write a quick summary of your reading immediately after you’ve finished. Capture the reading’s main points and discuss any questions you had or any ideas that were raised. Include the author and title, and write out an MLA citation for the source (see the appendix, Creating a Works Cited Page).

Check Your Understanding: Annotation

Check Your Understanding: Annotation

Print a hard copy* of the New York Times article, “Are We Loving Our National Parks to Death?”

Pre-read the article to gather some first impression ideas. Then read the article completely, annotating as you go.

*If you aren’t able to print a hard copy, carry out the following instructions using a piece of paper and a pen or pencil.

- Double-underline what you believe to be the topic or thesis statement in the article. (The thesis statement is one or two sentences that summarizes the article’s main point and tells what it’s about. The thesis statement can occur anywhere in the article—even near the end.)

- As you read, underline points that you find especially interesting. Make notes in the margins as ideas occur to you.

- Write question marks in the margin where questions occur to you, and make written margin notes about them, too.

- Circle all words you don’t understand. Then look them up! (Dictionary.com is a good online dictionary and even pronounces words so you’ll know how they sound.)

- When you’re finished, write a quick summary—several sentences or a short paragraph—that captures the article’s main points.

See the Appendix, Results for the “Check Your Understanding” Activities, for answers.

Do Quick Research

As you read, you might run into ideas, words, or phrases you don’t understand, or the text might refer to people, places, or events you’re unfamiliar with. It’s tempting to skip over those and keep reading, and sometimes that actually works. But keep in mind that when you read something written by a professional writer or academic, they’ve written with such precision that every word carries meaning and contributes to the whole. Therefore, skipping over words or ideas could change the meaning of the text or leave the meaning incomplete.

When you’re reading and come to words and ideas you’re unfamiliar with, you may want to stop and take a moment to do a bit of quick research. Google is a great tool for this—plug in the idea or word and see what comes up. Keep on digging until you have an answer, and then, to help retain the information, take a minute to write a note about it.

Discover What a Text is Trying to Say

All texts—whether fiction or nonfiction—carry layers of information, built one on top of the other. As we read, we peel those back—like layers in an onion—and uncover deeper meanings.

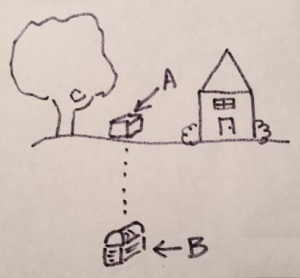

Take a look at Figure 1 to the right. I use this in the classroom to explain the “deeper meaning” concept to students. All texts and stories have surface meaning. In the sketch, this is represented by all the things we see above ground: the tree, the house, and the box (A), along with whatever is in it—even though the box may be closed, anyone who walks by can see it and explore it. These items are concrete and obvious. In “Goldilocks and the Three Bears,” for example, the surface story is about a little girl who goes for a walk in the forest, wanders into the bears’ home, gets into their belongings, and is frightened off.

But stories and essays also have deeper, hidden meanings. In Figure 1, there’s a buried treasure chest (B) deep underground, waiting to be discovered and opened. Texts are much the same—they each contain obvious, surface level meanings, and they each contain a buried prize as well. What’s the deeper meaning in “Goldilocks”? Most fables and fairy tales were designed to teach, warn, or scare. Perhaps the author wants us to think about what happens when we invade people’s privacy. Or maybe it’s about the drawbacks of curiosity. What do you think?

When working with a text, be aware of everything that is happening within it—almost as if you’re watching a juggler with several balls in the air at one time:

- Consider the characters or people featured in the text, their dialog, and how they interact.

- Be aware of the plot’s movement (in a fictional story) or the topic development (in a nonfiction story or essay) and the moments of excitement or conflict as the action rises and falls.

- Look for changes in time—flashbacks, flash-forwards, and dream sequences.

- Watch for themes (ideas that occur, reappear, and carry meaning or a message throughout the piece) or symbols (objects or ideas that stand for or mean something else; these carry meaning that we often understand quickly without thinking about it too much).

Examples of themes: coming of age, redemption, the nature of honesty, conflict, sacrifice.

Examples of symbols: full moon (typically suggests mystery), dark forest (danger or the possibility of being lost), white flag (surrender), a path or road (journey).

As you read, always look for both surface meanings and those buried beneath the surface, like treasure. That’s the fun part of reading—finding those precious hidden bits, waiting to be uncovered and eager to make your reading experience richer and deeper. Even if you just scratch the surface, you’ll learn more.

Explore the Ways the Text Affects You

When you work with a text, you enter into a conversation with it, responding with your thoughts, ideas, and feelings. The way each of us responds to any text has a lot to do with who we are: our age, education, cultural background, religion, ethnicity, and so forth.

As you explore a text, be aware of how you’re responding to it.

- Are you reading or exploring easily and fluidly, or are you finding it difficult to navigate the text? Why do you believe this is so?

- Do you find yourself responding with some sort of strong emotion? If so, why do you think that may be happening?

- Do formatting or structural issues (examples: unusual use of punctuation, use of dialect or jargon) affect your navigation of the text?

- Can you identify with the text’s central idea or the information it’s sharing?

- Have you had any experiences like those being described? Can you identify with the story?

- Are you able to identify the surface meaning?

- Have you explored the text’s deeper, hidden messages?

- Do you need to look up any words to do any quick research? If so, does this help you better understand the text?

- What questions do you have about the work?

Reflect

Whenever you finish a bit of college reading, it’s worth your time to stop and reflect on it. This not only helps you think about the content and what it means to you, but it also helps cement it within your memory, allowing you to recall the key ideas later and to apply them in other reading and writing situations.

Here are two ideas for post-reading reflection:

- Write in a personal reading journal.

- Angelo and Cross suggest writing a “minute paper.” To do this, take one minute to jot down a few sentences about something you learned or discovered while reading. Or ask yourself a question about the reading and write an answer. (See the entry for Angelo and Cross in the Appendix, “Works Cited in This Text.”)

Check Your Understanding: Reflecting on What You’ve Read

Check Your Understanding: Reflecting on What You’ve Read

First, read the New York Times article, “Period. Full Stop. Point. Whatever It’s Called, It’s Going Out of Style” by Dan Bilefsky (found at www.nytimes.com).

Next, write a minute paper (see description above) by jotting down a few sentences in response to one of these questions:

- Do you agree with the idea that the period is going out of style? Why or why not?

- Do you agree that ending a text message with a period affects the meaning of the message? Explain.

- What does the author mean when he suggests that leaving the period out of text messages is the “the punctuation equivalent of stagehands who dress in black to be less conspicuous”?

See the Appendix, Results for the “Check Your Understanding” Activities, for answers.

Troubleshoot Your Reading

Sometimes reading may seem difficult, you might have trouble getting started, or other challenges will surface. Here are some troubleshooting ideas.

Problem: “Sometimes I put my reading off or don’t have time to do it, and then when I do have time, well, I’m out of time.”

Suggestions: That’s a problem, for sure. I always suggest to students that rather than trying to do a bunch of reading at once, they try to do a little bit every day. That makes it easier.

If you’re stuck up against a deadline with no reading done, one suggestion is to do some good pre-reading. That should at least give you the idea of the main topic.

Another idea is to divide the total pages assigned by the number of available days, figuring out how many pages you’ll need to read each day to finish the assignment. Sometimes approaching the text in smaller pieces like this can make it feel more doable. Also, once you figure out how long it takes you to read, say, five pages, you can predict how much time it will take to read a larger section.

Problem: “If I don’t understand some part of the reading, I just skip over it and hope someone will explain it later in class.”

Suggestions: Not understanding reading can be frustrating—and it can make it hard to succeed on your assignments. The best suggestion is to talk with your teacher. Let them know you don’t understand the reading, and they should be able to help.

Another suggestion is to read sentence by sentence. Be sure you understand each word—if you don’t, look them up. As you read, master each sentence before going on to the next one, and then, at the end of a paragraph, stop and summarize the entire paragraph, reflecting on what you just read.

Yet another idea: use the Web and do a search for the title of the reading followed by the word ‘analysis.’ Reading what other people have said about the text may help you get past your stuck points. If you’re in a face-to-face classroom, asking a question in class will encourage discussion and will also help your fellow students, who may have the same confusions.

Problem: “I really don’t like to read that much, so I read pretty fast and tend to stick with the obvious meanings. But then the teacher is always asking us to dig deeper and try to figure out what the author really meant. I get so frustrated with that!”

Suggestions: College-level writing tends to have multiple layers of significance. The easiest way to think about this is by separating the “obvious or surface meaning” from the “buried treasure meaning.” This can actually be one of the most fun parts of a reading—you get to play detective. As you read, try to ask questions of the text: Why? Who? Where? For what reason? These questions will help you think more deeply about the text.

Problem: “Sometimes I jump to conclusions about what a text means and then later find out I wasn’t understanding it completely.”

Suggestions: This usually happens when we read too quickly and don’t engage with the text. The best way to avoid this is to slow down and take time with the text, following all the guidelines for effective and critical reading.

Problem: “When a text suggests an idea I strongly disagree with, I can’t seem to go any further.”

Suggestions: Aristotle was known for saying, “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.” As a college student, you must be ready to explore and examine a wide range of ideas, whether you agree with them or not. In approaching texts with an open and willing mind, you leave yourself ready to engage with a wide world of ideas—many of which you may not have encountered before. This is what college is all about.

Problem: “I’m a slow reader. It takes me a long time to read material, and sometimes the amount of assigned reading panics me.”

Suggestions: Two thoughts. One, the more you read, the easier it gets: like anything, reading improves with practice. And two, you’ll probably find your reading is most effective if you try to do a little bit every day rather than several hours of reading all at one time. Plan ahead! Be aware of what you need to read and divide it up among the available days. Reading 100 pages in a week may seem overwhelming, but reading 15 pages a day will be easier. Be sure to read when you’re fresh, too, rather than at day’s end, when you’re exhausted.

Problem: “Sometimes the teacher assigns content in an area I really know nothing about. I want to be an accountant. Why should I read philosophy or natural history, and how am I supposed to understand them?”

Suggestions: By reading a wide variety of texts, we don’t just increase our knowledge base—we also make our minds work. This kind of “mental exercise” teaches the brain and prepares it to deal with all kinds of critical and innovative thinking. It also helps train us to different reading and writing tasks, even when they’re not familiar to us.

Problem: “When I examine a text, I tend to automatically accept what it says. But the teacher is always encouraging us to ask questions and not make assumptions.”

Suggestions: What you’re doing is reading as a reader—reading for yourself and making your own assumptions. The teacher wants you to reach for the next level by reading critically. By engaging with the text and digging through it as if you’re on an archaeological expedition, you’ll discover even more about the text. This can be fun, and it also helps train your brain to explore texts with an analytic eye.

Problem: “I really hate reading. I’ve found I can skip the readings, read the Sparks Notes, and get by just fine.”

Suggestions: First, if you aren’t familiar with Sparks Notes, it’s an online site that provides summary and analysis of many literary texts and other materials, and students often use this to either replace reading or to better understand materials. You may be able to get by, at least for a while, with reading Sparks Notes alone, for they do a decent basic job of summarizing content and talking about simple themes. But Sparks isn’t good at reading texts deeply or considering deep analysis, which means a Sparks-only approach will result in your missing a lot of what the text includes.

You’ll also be missing some great experiences. The more you read, the easier reading becomes. The more you read deeply and critically and the more comfortable you become with analyzing texts, the easier that process becomes. And as your textual skills become stronger, you’ll find yourself more successful with all of your college studies, too. Reading remains a vital college (and life!) skill—the more you practice reading, the better you’ll be at it. And honestly, reading can be fun, too– not to mention a great way to relax and an almost instant stress reducer.

Check Your Understanding: Reflect on Your Own Reading Practices

Check Your Understanding: Reflect on Your Own Reading Practices

After reviewing the above section, identify one or two key issues from the list that you might relate to.

Consider how the possible suggestions might work for you.

Write a short plan—in one paragraph—that explains how you could implement a solution to help you improve your reading practices.

See the Appendix, Results for the “Check Your Understanding” Activities, for answers.

(adapted, in part, from The Word on College Reading and Writing by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear. This OER text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.)