Critical Reading Strategies

Andy Gurevich

Reading Critically

As you take on a broader range of writing assignments in your college classes, it can be helpful to read as a writer, often called reading to write. “Reading to write” means approaching reading material with a variety of tools that help prepare you to write about that reading material. These tools can include things like previewing related assignments or lectures prior to reading, specific note-taking methods while reading, and ways of thinking about and organizing the information after completing the reading.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

As we have learned in the “Building Strong Reading Skills” section of this text, critical reading is effective reading taken to the next step, but now we’re going to talk about how to use those reading skills to help us write about the texts we read. Instead of simply reading for your own purposes, you now will also read through the writer’s eyes, seeking to understand the deeper, interwoven meanings layered within a text. Critical reading involves the reader in grappling with the text—interacting with it.

The critical reader digs in and explores a text. They do some or all of the following:

- They analyze the structure of the piece. What kind of organization does it follow? Where is the thesis? What types of sentences and language are used? How are the paragraphs structured?

- They analyze the text itself, either exploring its content or its use of rhetoric, i.e., the ways the text uses language to make its message effective.

- They capture the text’s main points by summarizing its meaning.

- They critique the text, passing judgment on its effectiveness.

- They reach conclusions (make inferences) about the text.

- They combine their own ideas with the textual analysis to synthesize new ideas and insights.

You’ll begin, of course, by reading the text. Work your way through the suggestions in the “Read Effectively” section, found in the larger “Building Strong Reading Skills” section of this text.

Exploring the Structure of a Text

Exploring a text’s structure may sound a little complicated, but it really isn’t. We’re simply looking for how it’s been constructed or built, and then we’re thinking about how the structure supports the work the text is trying to do. The fancy literary terms for this are “form” and “function.” Form refers to the way the text is structured, while function refers to what it communicates to the reader.

Consider these questions when thinking about structure:

- How is the text organized? (Does it seem logical? Is it in time-related, chronological order? Does it skip around in time with flashbacks or flash-forwards?)

- Is it divided into obvious sections? Do the sections have headings, or are they just visually separated?

- Does the author use comparison/contrast, explore cause and effect, or examine a process to present their ideas?

- Is there a lot of detail and description in the text?

Does the author use dialog? - Does the author do anything unusual* or unexpected with the text?

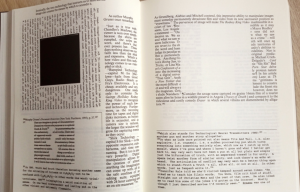

*Speaking of unusual texts, sometimes the author will do something unexpected with the text’s form in order to support its function. As an example, check out these examples from Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves, a novel that includes some extraordinary structures.

In the example shown to the right here, you can see some of the unusual ways Danielewski has arranged text on two of the pages. His book contains all sorts of different textual anomalies (something that deviates from the usual or standard approach); if you want to see more of them, go to Google and search for ‘House of Leaves’ and then ‘images.’ Throughout the text, his creativity with the textual layout echoes and supports what is happening within the story. It’s ridiculously cool, and if you’re curious about it, I recommend reading it. It’s a weird but worthwhile reading experience, and it brings home the idea of textual structure like nothing else can.

Dialectic Note-taking

A dialectical approach to taking notes sounds much more complicated than it is. A dialectic is just a dialogue, a discussion between two (or more) voices trying to figure something out. Whenever we read new material, particularly material that is challenging in some way, it can be helpful to take dialectic notes to create clear spaces for organizing these different sets of thoughts.

Creating Dialectic Notes

Start by drawing a vertical line down the middle of a fresh sheet of paper to make two long columns.

The Left Column

This column will be a straightforward representation of the main ideas in the text you are reading (or viewing). In it, you will note things like

- What are the author’s main points in this section?

- What kind of support is the author using in this section?

- Other points of significant interest?

- Note the source and page number, if any, so that you can find and document this source later

You candirectly quote these points, but do write them down as you encounter them, not after the fact. If you quote directly, use quotation marks; if you paraphrase, do not use quotation marks. Be consistent so that you don’t make more work for yourself when you start writing your draft. For more guidance with writing summaries, paraphrasing, and quoting, see the “Drafting” section of this text.

The Right Column

The right column will be the questions and connections you make as you encounter this author’s ideas. This might include

- Questions you want to ask in class

- Bigger-picture questions you might explore further in writing

- Connections to other texts you’ve read or viewed for this class

- Connections to your own personal experiences

- Connections to the world around you (issues in your community, stories on the news, or texts you’ve read or viewed outside of this class)

Bottom of the Page

It is often a good idea to leave space at the bottom of the page (or on the back) for additional notes about this piece you may want to write down based on what your instructor has to say about it or for comments and questions your peers make about it during class discussion.

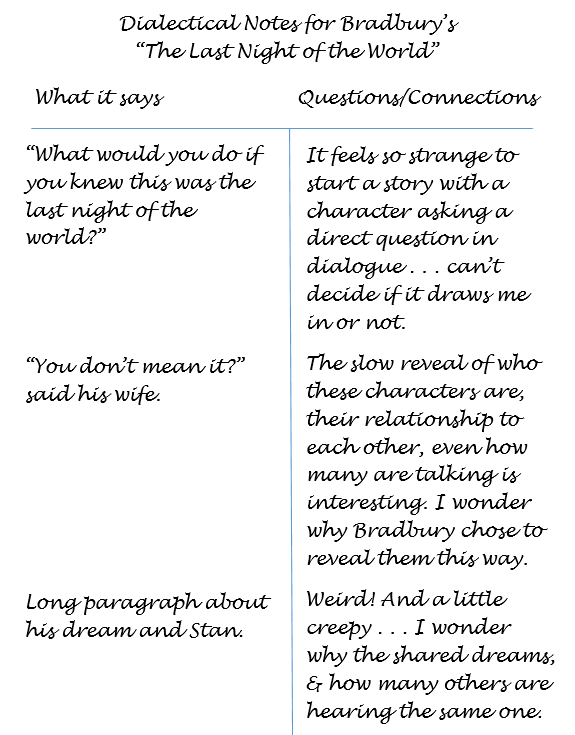

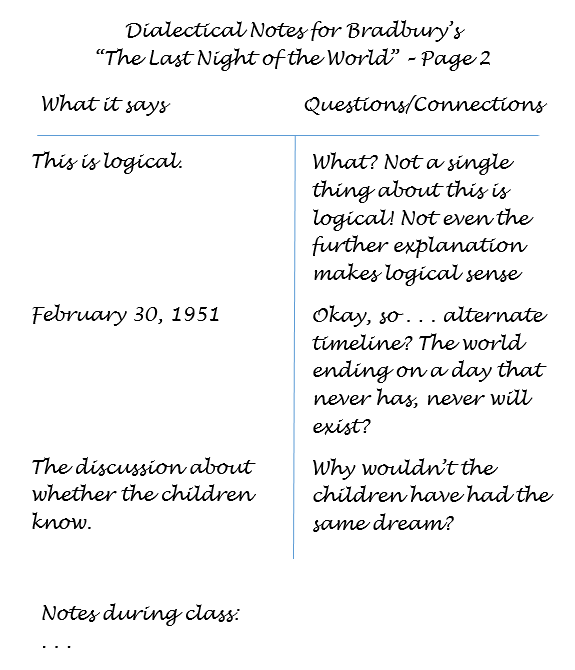

Example

Once you’ve finished the text and have taken your dialectic notes while reading it, you might have something that looks a bit like this (for the sake of the example, I read a story I’d never read before from an author I’m familiar with, so you could see genuine reactions to a first read):

Once you have this set of dialectic notes, there are a number of ways you can use them. Here are a few:

- They can help you contribute to class discussion about this piece and the topics it addresses.

- Significant questions you encountered while reading are already written down and collected in one place so you don’t have to sift back through the reading to re-discover those questions.

- These notes provide a place where many of your observations and thoughts about the piece are already organized, which can help you see patterns and connections within those observations. Finding these connections can be a strong starting point for written assignments.

- If you are asked to respond to this piece in writing, these notes can serve as a reference point as you develop a draft. They can give you new ideas if you get stuck and help keep the original connections you saw when reading fresh in your mind as you respond more formally to that reading.

Analyzing Content and Rhetoric

When we talk about rhetoric (REH-torr-ick), we’re talking about the ways we write and speak effectively and persuasively. We use rhetoric to explain, to describe, and to argue or persuade (see the glossary of terms).

In developing your reading and analysis skills, always think about what you’re reading, questioning the text—and your responses—as you read. Use the following questions to help analyze as you assess the text’s content and the ways it makes its points. Think of it as taking the text apart—dissecting it to see how it works:

- What is the author’s main point? Describe this in your own words. Do they make the point successfully? Is the point held consistently throughout the text, or does it wander at any point?

- What information does the author provide to support the central idea?Making a list of each point will help you analyze. Hint: each paragraph should address one key point, and all paragraphs should relate to the text’s central idea.

- What kind of evidence does the author use? Is it based more on fact or opinion, and do you feel those choices are effective? Where does this evidence come from? Are the sources authoritative and credible? (Learn more about the CRAP method for evaluating sources in the section titled “Finding Quality Texts.”)

- What is the author’s main purpose? Note that this is different that the text’s main idea. The text’s main idea (above) refers to the central claim or thesis embedded in the text. The author’s purpose, however, refers to what they hope to accomplish. For example, a cookbook is assembled in order to share recipes and cooking methods. But perhaps the author also wanted to include a group of treasured family recipes in hopes of sharing them with a wider cooking audience. The text has one purpose, while the author has an additional aim for the work.

- Describe the tone in the piece. Is it friendly? Authoritative? Does it lecture? Is it biting or sarcastic? Does the author use simple language, or is it full of jargon? Does the language feel positive or negative? Point to aspects of the text that create the tone; spend some time examining these and considering how and why they work. (Learn more about tone in in the section titled “Tone, Voice, and Point of View.”)

- Is the author objective, or does he/she try to convince you to have a certain opinion? Why does the author try to persuade you to adopt this viewpoint? If the author is biased, does this interfere with the way you read and understand the text?

- Do you feel like the author knows who you are? Does the text seem to be aimed at readers like you or at a different audience? What assumptions does the author make about their audience? Would most people find these reasonable, acceptable, or accurate?

- Does the text’s flow make sense? Is the line of reasoning logical? Are there any gaps? Are there any spots where you feel the reasoning is flawed in some way?

- Does the author try to appeal to your emotions? Does the author use any controversial words in the headline or the article? Do these affect your reading or your interest?

- Do you believe the author? Do you accept their thoughts and ideas? Why or why not?

Check Your Understanding: Jargon

Check Your Understanding: Jargon

Jargon refers to language, abbreviations, or terms that are used by specific groups— typically those people involved in a profession. Using jargon within that group makes conversation simpler, and it works because everyone in the group knows the lingo.

The problem with using jargon when writing is that if your reader has no idea of what those terms mean, you’ll lose them.

- Read this paragraph that relies heavily on jargon:

Those who experience sx of URI might consider visiting a PCP. This should happen ASAP with pyrexia >101, enlarged cervical nodes, purulent nares drainage, or tonsillar hypertrophy. Tx may include qid antibios, ASA, fluids, and a mucolytic.

If you’re in a medical field, you probably understood that paragraph. Otherwise, it probably sounded like another language! - Now read this translation in lay (non-jargon) terms:

Those who have cold symptoms might consider visiting their primary care provider. This should happen quickly if there is fever over 101, swollen glands in the neck, green or yellow drainage from the nose, or inflamed, swollen tonsils. Treatment may include antibiotics, aspirin, fluids, and medications designed to loosen phlegm and make it easier to cough.

That’s quite a change, yes? It’s a good example of why we usually want to avoid jargon, only use it with an audience that understands it, or explain each term carefully as we use them. - What did you discover about jargon? What areas are you familiar with that may have their own types of jargon? Write a paragraph that discusses your experience with or ideas about this topic.

See the Appendix, Results for the “Check Your Understanding” Activities, for answers.

Sentence-Level Analysis

Sometimes it can be helpful to examine the way sentences are used in a text. Ask the question, what is making the sentences work? Let’s consider a few ideas.

Begin by considering the sentence length. Is the text comprised of mostly short sentences, mostly long (or really long) sentences, or a mixture of both?

Short sentences are a perfectly fine addition to any essay work. But if overused, they can feel boring and monotonous.

I needed to be at work early. I set my alarm for 5:00 am. It went off on time, and I got up. I showered and dressed. I ate cereal for breakfast. I had orange juice, too. My drive to work went well. I only hit three lights. Traffic wasn’t bad. I found a good parking place at work. I walked into the office early.

![]()

Try reading these examples aloud. This will help you “hear” their flow in a way you cannot by simply reading silently with eyes alone. Reading aloud is really the only way to hear the sound of writing.

In the above example, every one of those sentences is correct and perfectly legal in terms of grammar and structure. But how does it sound? A little choppy? Repetitive? Flat?

Now let’s look at the same paragraph, adjusted to combine the short sentences into much longer ones—and again, read it aloud:

I needed to be at work early, so I set my alarm for 5:00 am. It went off on time, and I got up, showered, dressed, ate cereal for breakfast, and had orange juice, too. My drive to work went well because I only hit three lights, traffic wasn’t bad, I found a good parking place at work, and I walked into the office early.

Once again, each of the sentences in the above example is grammatically correct. But how does the sample sound now? It seems to go on and on for a bit, doesn’t it? Longer sentences—especially once after another—can be a little hard to follow.

Let’s see if we can find a happy medium, creating a paragraph that includes both long and short sentences (yes, read it aloud again, please):

I needed to be at work early, so I set my alarm for 5:00 am. It went off on time. I got up, showered, dressed, and had cereal and orange juice for breakfast. My drive to work went well. I only hit three lights, and traffic wasn’t bad. I found a good parking place at work and walked into the office early.

You’ll probably agree that the final sample has the best, most fluid sound. Why? When we humans speak, we tend to speak in a mixture of long sentences, short sentences, and incomplete sentences—not to mention single words and short phrases. Thus, when we use varying sentence lengths in our writing, it sounds more conversational to our ear. Reading text composed of mixed-length sentences is both easier to do and easier to understand.

That said, sentence length can be used to create specific effects, too. Long, complicated sentences are often used in description or to create a rhythmic, flowing feel. In contrast, short sentences may be used for emphasis or to ramp up a feeling of anxiety or suspense.

Check Your Understanding: Sentence Length

Check Your Understanding: Sentence Length

Consider this long sentence from the children’s book, Stuart Little, by E.B. White:

In the loveliest town of all, where the houses were white and high and the elm trees were green and higher than the houses, where the front yards were wide and pleasant and the back yards were bushy and worth finding out about, where the streets sloped down to the stream and the stream flowed quietly under the bridge, where the lawns ended in orchards and the orchards ended in fields and the fields ended in pastures and the pastures climbed the hill and disappeared over the top toward the wonderful wide sky, in this loveliest of all towns Stuart stopped to get a drink of sarsaparilla.

- The above passage is a single, long, complex sentence and is grammatically correct. How did you feel when you read it? What kind of mood or tone did it create? Could you imagine the place being described?

- Now, consider this excerpt from a piece by Ben Montgomery, written as he covered a state football championship:

“Complete pass. Again. Clock’s ticking. Again. Down the field they go. The kid can’t miss. The Panthers are nearing the end zone….The whole place is on its feet. Ball’s on the 5-yard line. Marve takes the snap. Drops back. Throws.” - Montgomery’s piece is built of short sentences, sentence fragments, and even single words. How did you feel when you read this? What kind of mood or tone did it create? Can you hear the difference from the Stuart Little passage?

- What have you discovered about the effect of sentence length?

- Try your hand at playing with sentence length. Imagine the most beautiful place you’ve ever been. Write a few lines that describe the place. Aim for writing long, flowing sentences that include lots of sensory description: sight, sound, texture, etc. Now imagine something you’ve done that made you anxious or frightened. Write a few sentences that recreate the scene and sensations. Use short, abrupt sentences to ramp up the tension.

See the Appendix, Results for the “Check Your Understanding” Activities, for answers.

Point of View

photophilde is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Point of view (PoV) refers to the writer’s perspective as they explain what’s happening around them or tell a story. We describe writing as being in the first, second, or third person.

First person PoV

First person PoV uses pronouns like I, me, us, our, and we.

- When you read a passage written in first person, it’s as if you’re inside that person’s head, seeing through their eyes. You think what they think, see what they see, and know what they know.

- The strength of first person is in the way it shares emotional intensity. We feelwhat the narrator feels. We respond to events along with them.

- The weakness of first person is its lack of significant information. We only know what the narrator knows; we can’t get into the heads of other characters who are nearby. We also only see what that narrator sees; we can’t see what else is going on around them or even around the next bend in the road. The first person narrator’s knowledge of all the story’s events is limited.

- Writers tend to use first person when they want to convey emotional intensity, as in a personal narrative, or when they want us to know the narrator intimately.

Example

“I could picture it. I have a habit of imagining the conversations between my friends. We went out to the Cafe Napolitain to have an aperitif and watch the evening crowd on the Boulevard” (from Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises).

Second person PoV

Second person PoV uses pronouns like you, your, and yourself.

When you read a passage written in second person, it’s as if the writer is talking directly to you.

- The strength of second person is in a direct connection with narrator and reader; when reading second person, you feel as if you’re having a conversation with the narrator. This is especially effective when they are giving instructions.

- The weakness of second person is that it limits the audience by making it seem the narrator is talking to only one person. It can create a strange “dreamy” tone that may make the text feel strange. It can also feel aggressive or accusatory.

- Writers may use second person when they want to talk directly to one reader, give instructions, or create a dreamy or meditative passage.

Examples

“You have brains in your head. You have feet in your shoes. You can steer yourself any direction you choose. You’re on your own. And you know what you know” (from Dr. Seuss’ Oh, the Places You’ll Go!).

“You are walking through a forest…. It is peaceful…. You breathe deeply and slowly as you listen to the forest sounds around you…. You hear the sounds of leaves underfoot as you follow the path…. You find a fallen log…. You sit down” (meditation sequence).

“When you fill out the form, use a #2 pencil” (instructions).

Third person PoV

Third person PoV uses pronouns like she, he, it, them, and their and omits “I.”

- When you read a passage written in third person, you experience a perspective that is all-seeing and all-knowing. A third person narrator can see past, present, and future; they can also know whatever any character knows as well as how that character feels and thinks. They have a full view of whatever is in front of, behind, beside, above, or below them. In short, they can see the entire scene. Third person is all about facts.

- The strength of third person is its ability to be informative. It sees all, knows all, and shares this with the reader. Because it does not use the “I” voice, it feels objective and smart.

- The weakness of third person is its lack of intimacy. It’s focused on information and thus tells us little about emotion and feelings. We end up knowing a lot about the setting and events and not much about the human nature of the characters, what they’re thinking, or what they plan to do next.

- Writers tend to use third person when they want to write objectively without sounding emotional or biased. Much college, research, and professional writing is done in third person. And note that there are a number of sub-forms of third person; you may hear more about these if you study creative writing.

Example

“The seller of lightning-rods arrived just ahead of the storm. He came along the street of Green Town, Illinois, in the late cloudy October day, sneaking glances over his shoulder. Somewhere not so far back, vast lightnings stomped the earth. Somewhere, a storm like a great beast with terrible teeth could not be denied” (from Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes).

Word Choice

is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Does the author use simple language that all readers understand? Or do they use language that contains complex language and may not be understood by all readers?

Simpler language can help make a text available to everyone. On the other hand, overly-simple language may frustrate some readers. Using more complex language allows a writer to add deeper layers of information and meaning to a text, and this can work if the audience is familiar with the language (or jargon) being used. But if they’re not, they may find the text confusing, irritating, or even impossible to understand.

Do they do anything unusual with words or punctuation?

Sometimes writers do this in order to create a certain sound or dialect within a text. Dialect is a language or language-sound that is known by and particular to a specific group of people or a specific geographical region. For example, think about how people define a sweet carbonated drink as “pop,” “soda,” or “Coke” depending on what part of the U.S. they live in.

Consider this example from the book, To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee; it’s set in the south and written in words that create a distinct dialect:

“Reckon I have. Almost died first year I come to school and et them pecans—folks say he pizened ‘em and put ‘em over on the school side of the fence.”

Translation: “I suppose I have. I almost died the first year I came to school and ate those pecans. Folks say he [Mr. Radley] poisoned them and put them on the school’s side of the fence.”

Paragraph Analysis

When exploring a text, consider the structure and arrangement of paragraphs. Follow the colors in the discussion and example below. Note, if you have difficulty distinguishing between these colors or if you’re not using a color copy of the text, the first shaded part identifies the topic sentence, the shaded part in the middle identifies the support, and the final shaded part identifies the transition.

In terms of structure, an “academic” paragraph includes a topic sentence, which introduces* the paragraph’s main idea. It then offers several sentences (or at least one, as a minimum) to support or explain the topic sentence. Finally, it concludes with a sentence that helps transition to the next paragraph.

*Note that the topic sentence is often, but not always, the first sentence in the paragraph. You’ll hear more about that later. (For more about topic sentences see “Writing Paragraphs” in the “Drafting” section of this text.)

Here’s an example:

Single-use plastic water bottles cause dangerous substances to “leach” into the soil and water (Macklin). The bottles typically don’t begin to break down for one hundred years, or even longer. Their decomposition may be speeded up by extreme weather conditions, e.g., very hot or very cold temperatures. As they break down, they release dangerous chemicals like bisphenol-A into the soil. Bisphenol-A is an endocrine disruptor, i.e., it can affect the levels of hormones within the human body, creating disease. In addition, BPA is known to be carcinogenic (cancer-causing) in humans. As these chemicals accumulate in the soil, they eventually sink into the water table, contaminating the water (O’Connor). Making these threats even more frightening is the fact that there is currently no known technology for removing BPA and other leachates from the soil and water once they’re there.

Writers may choose to use short or long paragraphs to create specific effects—much the same as using short and long sentences. Short paragraphs can build tension or a sense of expectation, while long ones may create a “stream of consciousness” feeling, in which the narrator’s thoughts, feelings, and reactions are given in a continuous, rambling flow.

The classic arrangement of paragraphs in a text may be described as “linear” or time-based. In other words, the narrator typically starts at the beginning and moves logically to the end. Sometimes a writer will use flashbacks, flash-forwards, or dream/imaginative sequences to affect the usual flow of time in the story or to provide additional information. For example, a flashback allows the reader to learn something about the story’s past they wouldn’t have known otherwise.

Summarizing a Text

When you finish reading a text, it’s a great idea to stop for a moment and write a summary of what you just read.

A good summary accomplishes the following:

- It identifies or names the piece and its author(s) and states the main purpose of the text.

Example: In his essay, “Consider the Lobster,” writer David Foster Wallace asks readers to consider the ethical implications of feasting on lobsters. (You can find a copy of this essay online at gourmet.com.) - It captures the text’s main points.

- It does not include the reader’s opinions, feelings, beliefs, counterarguments, etc.

- It is short. The idea of a summary is to “boil down” or condense a text to just a few sentences.

Most important of all, when you create a summary of a text, it helps you review what you read and helps your brain capture the main ideas. Writing these down cements the memories; this will help you recall them more easily later on.

Check Your Understanding: Summarizing a Text

Check Your Understanding: Summarizing a Text

Read “Replace Annual Physicals with Real-Time Biomarker Monitoring.” (This article by Alex Berezow and Eric Tan can be found online at the Scientific American blog site.)

Write a summary of this text, using the above guidelines.

See the Appendix, Results for the “Check Your Understanding” Activities, for answers.

Critiquing a Text

Let’s review:

- When we summarize a text, we capture its main points.

- When we analyze a text, we consider how it has been put together—we dissect it, more or less, to see how it works

Here’s a new term: when we critique (crih-TEEK) a text, we evaluate it, asking it questions. Critique shares a root with the word “criticize.” Most of us tend to think of criticism as being negative or mean, but in the academic sense, doing a critique is not the least bit negative. Rather, it’s a constructive way to better explore and understand the material we’re working with. The word’s origin means “to evaluate,” and through our critique, we do a deep evaluation of a text. (see the glossary of terms).

When we critique a text, we interrogate it. Imagine the text, sitting on a stool under a bright, dangling light bulb while you ask, in a demanding voice, “What did you mean by having Professor Mustard wear a golden yellow fedora?”

Okay, seriously. When we critique, our own opinions and ideas become part of our textual analysis. We question the text, we argue with it, and we delve into it for deeper meanings.

Here are some ideas to consider when critiquing a text:

- How did you respond to the piece? Did you like it? Did it appeal to you? Could you identify with it?

- Do you agree with the main ideas in the text?

- Did you find any errors in reasoning? Any gaps in the discussion?

- Did the organization make sense?

- Was evidence used correctly, without manipulation? Has the writer used appropriate sources for support?

- Is the author objective? Biased? Reasonable? (Note that the author might just as easily be subjective, unbiased, and unreasonable! Every type of writing and tone can be used for a specific purpose. By identifying these techniques and considering why the author is using them, you begin to understand more about the text.)

- Has the author left anything out? If yes, was this accidental? Intentional?

- Are the text’s tone and language text appropriate?

- Are all of the author’s statements clear? Is anything confusing?

- What worked well in the text? What was lacking or failed completely?

- What is the cultural context* of the text?

*Cultural context is a fancy way of asking who is affected by the ideas and who stands to lose or gain if the ideas take place. When you think about this, think of all kinds of social and cultural variables, including age, gender, occupation, education, race, ethnicity, religion, economic status, and so forth.

These are only a few ideas relating to critique, but they’ll get you started. When you critique, try working with these statements, offering explanations to support your ideas. Bring in content from the text (textual evidence) to support your ideas.

Drawing Conclusions, Synthesizing, and Reflecting

photo by Andy Field is

licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Synthesizing

To synthesize is to combine ideas and create a completely new idea. That new idea becomes the conclusion you have drawn from your reading. This is the true beauty of reading: it causes us to weigh ideas, to compare, judge, think, and explore—and then to arrive at a moment that we hadn’t known before. We begin with simple summary, work through analysis, evaluate using critique, and then move on to synthesis.

For example, many people read J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye at some point during their lives, often during high school. The book focuses on an angsty, rebellious teen who relates aspects of his teenage experiences, and he does this from his room in a mental institution. In the end, the teen understands more about himself and the world, and he begins to consider his possible future.

Many teens read this story and see themselves in it; grappling with the ideas in the text helps them better understand themselves and often encourages them to reach for their own futures. This is an example of how they draw their own conclusions from the text and synthesize their own directions and ideas.

Most of us can point to one or two books that have been life-changing—books that have held us captive for a moment in time and shaped our outlook. These are moments of synthesis. If this hasn’t happened to you yet, grab a good book (ask a teacher or librarian if you need suggestions), pour a cup of tea, and start reading.

Reflecting

After a period of critical reading, it’s time to reflect. Go back to the earlier discussion in the “Reflect” section (see “Building Strong Reading Skills” in the table on contents). Make some spontaneous notes, write in a writing journal, create a minute paper, or in some way write a few words that capture your experience.

(adapted, in part, from The Word on College Reading and Writing by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear. This OER text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.)