Chapter 9 – Patterns of Development (Cause/Effect)

Cause/Effect

Cause and effect essays examine causes, describe effects or do both. Cause / Effect, like narration, links situations and events together in time, with causes preceding effects. But causality involves more than sequence: cause / effect analysis explains why something happened—or is happening—and predicts what probably will happen.

- Read this information on the steps to Writing a Cause/Effect Essay

- View the embedded video (9 min) :

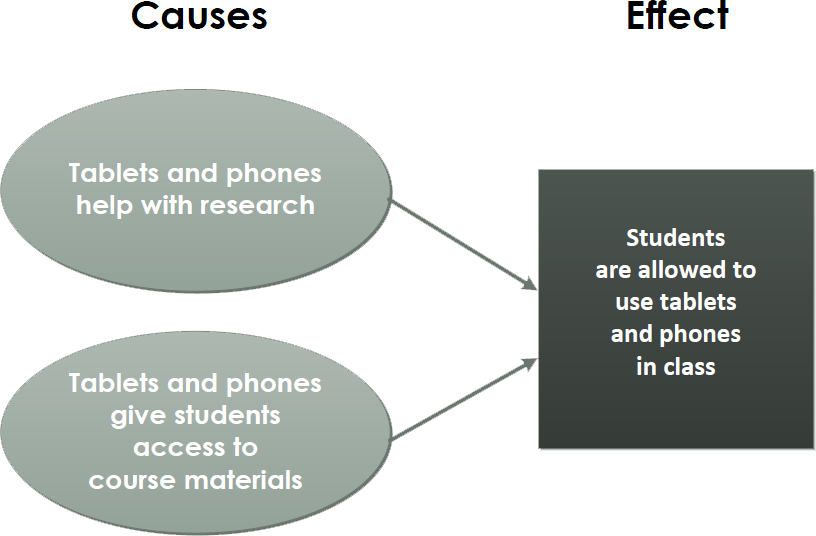

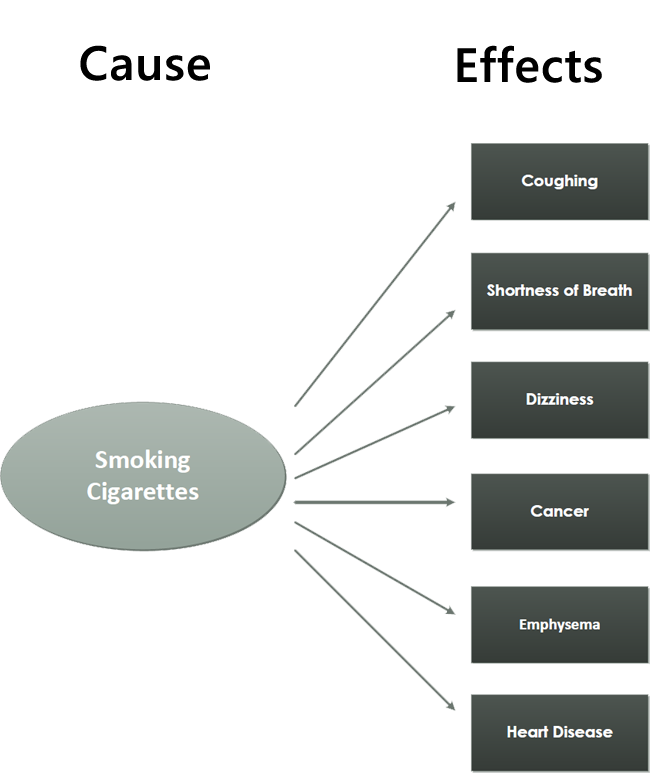

Sometimes several different causes can be responsible for one effect:

Understanding Main & Contributory Causes

Even when you have identified several causes of a particular effect, one—the main cause —is always (or usually) more important than the others —the contributory (or secondary) causes. Understanding the distinction between the main (most important) and the contributory (less important) causes is vital for planning a cause / effect essay (and for analyzing one as well) because once you identify the main cause, you can emphasize it in your essay (probably in your thesis statement and pattern of development) and downplay the other causes. How, then, can you tell which cause is the most important? Sometimes the main cause is obvious, but often it is not. Examine the diagram below.

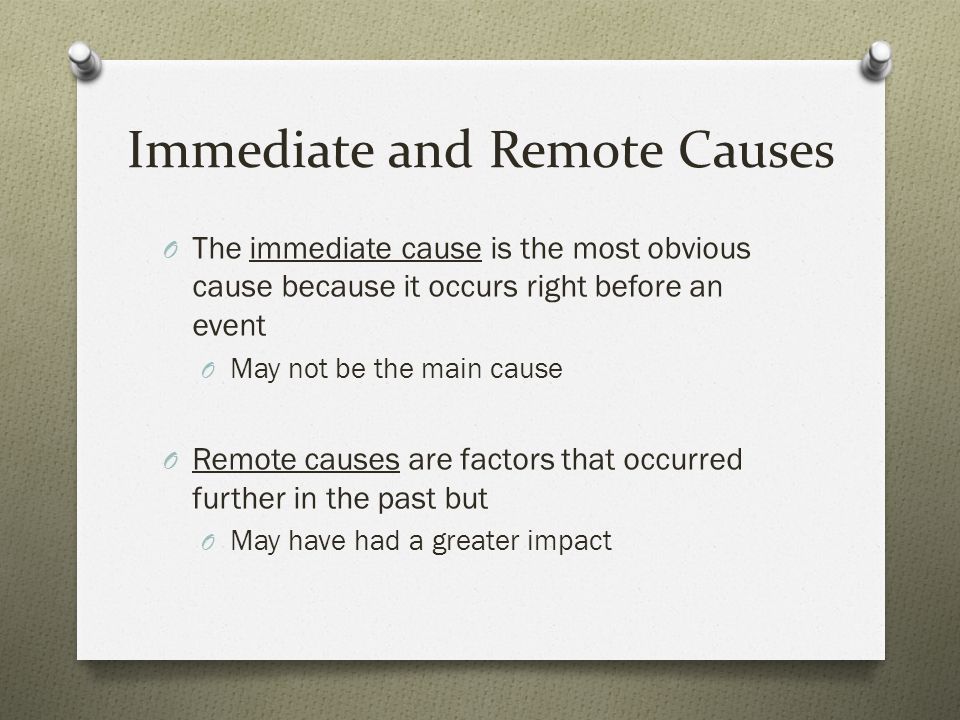

Understanding Immediate & Remote Causes

Another important distinction is the difference between an immediate cause and a remote cause. An immediate cause closely precedes an effect and is therefore relatively easy to recognize. A remote cause is less obvious, perhaps because it involves something in the past or far away. Assuming that the most obvious cause is always the most important can be dangerous as well as shortsighted.

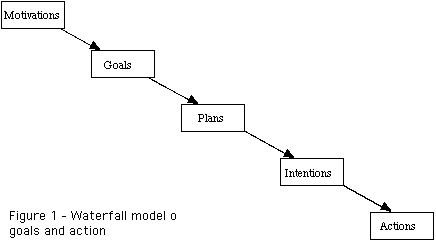

Understanding Causal Chains

Sometimes an effect can also be a cause. This is true in a causal chain, where A causes B, which causes C, which causes D.

In causal chains, the result of one action is the cause of another. Leaving out any link in the chain, or failing to put any link in its proper order, can destroy the logic and continuity of the entire chain.

Avoiding Post Hoc Reasoning

When exploring causal relationships in your own writing or in someone else’s, you should not assume that just because event A precedes event B, that event A must have caused event B. This illogical assumption, called post hoc reasoning, equates a chronological sequence with causality. When you fall into this trap—assuming, for instance, that you failed an exam because a black cat crossed your path the day before—you are mistaking coincidence (and chronology) for causality. Proving causation is a slow, methodical and academic process that requires a great amount of research, analysis and reflection on the nature of the causal relationships you are attempting to explore.