3 Access to care issues

“US Healthcare system Chapter 8” by Deanna L. Howe, Andrea L. Dozier, Sheree O. Dickenson, University of North Georgia Press is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

3.1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Define access to healthcare

- Discuss barriers to healthcare

- Define health literacy

- Explain initiatives to increase access to healthcare

- Describe possible improvements in the healthcare system

3.2 KEY TERMS

- access

- civilian

- equitable care

- health-seeking behaviors

- high deductible

- health disparities

- health literacy

- usual place of healthcare

3.3 INTRODUCTION

Having good health contributes to quality of life. Knowing that healthcare resources are available and easily accessible without depleting most of one’s resources in times of need provides a sense of security. In this chapter, we explore the degree to which persons in the U.S. are without access to healthcare, barriers to healthcare access, consequences of inadequate access to healthcare, and possible measures to improve healthcare in the immediate future.

3.4 ACCESS TO HEALTHCARE

What does access to healthcare mean? Where is the U.S. regarding access to healthcare for the population? In 1993, the Institute of Medicine defined access to healthcare as “the timely use of personal health services to achieve the best possible health outcomes” (IOM, 1993, p. 31). The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP, 2019a) uses this definition and lists three steps for obtaining access to needed healthcare services: (1) entrance into the system, usually through health insurance; (2) obtaining needed services within an accessible location; and (3) finding the right patient-provider relationship where communication, mutual trust, and respect are obtained. All three are essential in obtaining appropriate healthcare services.

Entrance into the System

Possessing health insurance may be considered as the gateway into the healthcare system. Without insurance coverage, most individuals are not willing to seek healthcare services unless faced with a life-threatening emergency—arguably, because of the expense. Hospital emergency departments are not allowed to turn anyone away because of the lack of health insurance. Conversely, physician offices can refuse to accept patients without insurance. Moreover, physician’s offices may turn patients away if they have only Medicaid; some also refuse Medicare.

Public health departments provide free or reduced-priced services to community members. Low-income pregnant women are eligible for Medicaid, and children of low-income families are eligible for Medicaid or state-sponsored insurance for children. Medicare is available to individuals with disability, who are on dialysis, or those age greater than 65 years. Of importance to note is that individuals’ being eligible for insurance does not mean they are automatically enrolled or obtain insurance. However, without insurance, unless paying with cash, an individual will most likely have a difficult time accessing the healthcare system.

Pause and Reflect

Should physicians be able to turn patients away who have Medicaid?

Should state or federal government require physicians to accept Medicaid patients?

What sort of incentives might state or federal government provide to physicians so they will begin to or increase acceptance of Medicaid patients?

First Person Perspective

Mr. J., M.A., is the Deputy Head for the Center for German-American Educational History

Source: Original Work

Attribution: Deanna Howe

License: CC BY-SA 4.0

In college, I lost health insurance coverage through my parents—this was before the Obama-era mandate which allowed dependents to stay on their parent’s health insurance coverage until they turned 26. Like a lot of college students, I gambled and went without health insurance, thinking that being young and healthy, I could spare the expense. I avoided going to the doctor and dentist for checkups, fearing the costs. I also would try to tough out illnesses, which ended up causing me to go to urgent care for a bronchial infection—something I could have avoided had I been able to go to the doctor without worry.

Still thinking I could manage on my own, life had other plans and I got in a serious car accident. My car was totaled and, because it had flipped over, paramedics forced me to take an ambulance ride to the nearest hospital. After running tests, the doctors determined that I was fine. Although I was very lucky to walk away from the accident with nothing more than a sore back, my lack of health insurance coverage impacted me negatively. Although my car insurance provider covered the hospital visit, it refused to cover my ambulance ride. This ended up costing me over $1,000, and I was soon dealing with aggressive debt collectors. The worst part about my story is knowing that this ambulance ride was relatively cheap compared to what many young people in my situation have gone through.

First person perspective vignette collected and created by D. Howe, 2020.

For your consideration:

Mr. J. describes a time when he didn’t have health insurance. Like many others without health insurance coverage, Mr. J. avoided going to the doctor or seeking routine care and also tried to “tough it out” in times of illness. Access issues to medical care are common when someone doesn’t have health insurance.

- Are there any services available that Mr. J. could have used in order to get the healthcare he needed during times of illness?

- What about for yearly check-ups when he isn’t sick?

- Have you ever known someone without health insurance?

- Did they also have access issues to healthcare services?

According to Cohen et al. (2019), 2018 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from HHS and the CDC reveal that 30.4 million civilian individuals (9.4% of the noninstitutionalized population) were without health insurance coverage at the time of the interview, and this result shows a decrease in the uninsured over the last eight years. It is important to note that statistics may vary slightly depending on which data are used. Berchick et al. (2019) provide statistics from two U.S. Census Bureau surveys—data retrieved from a nationwide survey from the U.S. Department of Commerce, the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC); and a state-based survey, the American Community Survey (ACS). Berchick et al. report 27.5 million persons without health insurance, 8.5% of the total noninstitutionalized population in 2018 (compared to 9.4% from Cohen et al., 2019). Berchick et al. report this as a slight increase of uninsured persons from 2017. Over two-thirds of the insured population had private health insurance, while the rest of those insured were covered by public health insurance (Medicare or Medicaid) (Cohen et al., 2019). Other interesting and important data obtained in the NHIS 2018 survey among age groups are as follows:

- Ages 0-17 years: 5.2% were uninsured, 41.8% had Medicaid or

Medicare, and 54.7% had private insurance - Ages 18-64: 13.3% were uninsured; 19.4% had Medicaid or Medicare;

and 68.9% (136.6 million) had private insurance - Ages 25-34: the age group that lacked health insurance the most in

2018. Only 17% of individuals had a form of health insurance (Cohen

et al., 2019).

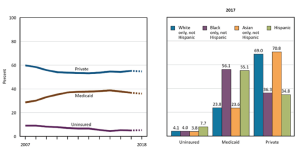

At first glance, the number of children uninsured is alarming, when considering most children are eligible for insurance from federal or state funds. Berchick et al. (2019) found that the children without insurance were most likely to be from families with income categories of at or above 400% of poverty income level. Although findings were nonsignificant, the data thus indicates that most uninsured children live in high-income families, families possibly without any insurance for any family member. Two statistically-significant findings by Berchick et al. were that more uninsured children lived in the South and were of Hispanic descent. This is congruent with the NHIS 2018 findings that the racial characteristics of uninsured children reveal the least likely to be insured were Hispanic children (7.7%); followed by non-Hispanic whites (4.1%); non-Hispanic Blacks (4.0%); and non-Hispanic Asian (3.8%) children (NCHS, 2019) (Figure 3.2).

NOTES: Estimates for 2018 are preliminary and are shown with a dashed line. Health insurance categories are mutually exclusive. A small percentage of children are covered by Medicare, military plans, or other plans. Estimates for this group are not presented.

Source: Health, United States 2018

Attribution: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

License: Public Domain

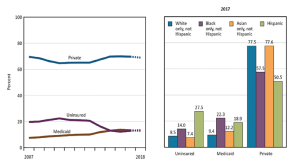

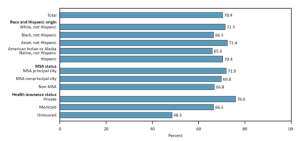

Probably not surprisingly, the largest age group lacking health insurance in the U.S. is the age group 25-34 years, most of whom are no longer covered by their parent’s insurance. This age group may be graduating from college and having difficulty finding full-time employment. Berchick et al. (2019) found that those working less than full-time and/or less than year-round were more likely to be uninsured. For all adults, those of Hispanic origin were the most likely to be uninsured, followed by Blacks, Whites, and then Asians (NCHS, 2019). Data was not provided concerning legal citizenship. Importantly, health-wise, the NIHS (NCHS) discovered Hispanic persons had the highest rate of diabetes. See Figure 3.3 below for health insurance coverage for adults aged 18-64 and ethnicity.

NOTES: Estimates for 2018 are preliminary and are shown with a dashed line. Health insurance categories are mutually exclusive. A small percentage of people are covered by Medicare, military plans, or other plans. Estimates for this group are not presented.

Source: Health, United States 2018

Attribution: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

License: Public Domain

Obtaining Needed Services Within an Accessible Location

There is a shortage of primary care physicians throughout the U.S. Numbers of advanced practice professionals (best known as advanced practice providers, sometimes also called physician extenders)—nurse practitioners and physician assistants—are increasing throughout the nation. Yet, at the present time, primary care services may not be available in many locations. Obtaining specialty services may not be available either. Important to note is that many locations offer public health departments or community health services. Having a healthcare provider or healthcare services in close proximity is essential for individuals to receive the appropriate care when healthcare is needed and in a timely manner. Moreover, equitable care with improved health outcomes and reduced healthcare costs occurs when individuals have healthcare services provided and utilized on a regular basis (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [ODPHP], 2019a).

Finding the Right Patient-Provider Relationship Where Communication, Mutual Trust and Respect are Obtained

Having a healthcare provider who demonstrates caring behaviors and attitudes is important in a healthcare provider-patient relationship. Caring is shown when there is respect and a non-judgmental attitude towards someone regardless of the individual’s culture, race, religion, ethnicity, gender, age, or disability. Caring and respect lead to trust and open communication. Trust and open communication lead to increased health-seeking behaviors and eventually lower healthcare costs due to decreased emergency room and outpatient clinic visits (ODPHP, 2019a). Improved health-seeking behaviors also lead to a decrease in chronic illness and mortality (ODPHP, 2019a).

BARRIERS TO HEALTHCARE

In addition to lack of health insurance, lack of accessible and appropriate healthcare services, and inability to find the “right” healthcare provider, there are other barriers to healthcare in the U.S. Inadequate health insurance, not having a “usual” place of obtaining healthcare, the high costs of healthcare, not obtaining an appointment in a timely manner, having a language barrier, low health literacy, and health disparities for certain parts of the population are all barriers to receiving adequate healthcare and are discussed next. Factors that may influence these barriers are also discussed.

High Cost of Healthcare

As technology continues to evolve and improve, quicker and more reliable diagnostic tests are available, as well as more efficient medications with fewer side effects, all of which increases the costs of healthcare. Governmental health plans and many insurance plans are slow to approve and pay for new technology, including diagnostic tests, medications, and equipment. Physicians, however, order the most up-to-date diagnostic tests, medications, and equipment which they feel will help patients or improve their health. Often, patients need to take several medications to combat their disease processes. For example, it is not uncommon for persons with high blood pressure to be on three different medications to maintain a normal blood pressure. Kirzinger et al. (2019) found that individuals who have the most difficulty affording their prescription medications are taking four or more prescription medications; spending $100 or more per month on medications; are in the 50–64 year old age range; describe themselves in either fair or poor health; and have an income less than $40,000 annually. Obviously, having to pay exorbitant costs for medications may prevent individuals from receiving the healthcare they need. These findings may indicate that individuals who are aging— but not old enough for Medicare—and who are possibly in the lower income levels may be developing chronic illnesses in their younger years of age. Examining similar information as the Kirzinger report, the federal government’s latest data concerning delay or nonreceipt of healthcare are found in the 2017 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) (NCHS, 2019, Trend Table 29) where 320,182 individuals (adults or an adult speaking for a child in the home) were interviewed concerning delay or nonreceipt of needed medical care due to cost, nonreceipt of needed prescription drugs due to cost, and nonreceipt of needed dental care due to cost. Results from the 2017 survey were compared to results from 1997, 2005, and 2010. In 2017, 7.4% of respondents stated they delayed or did not receive needed medical care due to costs. This percentage was the lowest percentage in the 10- year recorded period. Of those responding to the question about not receiving needed prescription drugs due to cost, 5.1% stated they had not received medications as needed. Only the year 1997 was lowest, with 4.8% not receiving medications due to cost. Of those responding that they didn’t receive needed dental care due to cost, 9.5% agreed that they had not received dental care. Again, this was the second lowest percentage, with 8.6% responding in 1997 that this was a problem. Although these are relatively small percentages, the goal is that no one delays or doesn’t receive medical care when needed.

Health Insurance Costs and the Relationship to Access

Costs associated with health insurance, such as high deductibles, copays, and out-of-pocket expenses, can be a barrier to healthcare. Many individuals have private insurance with high deductibles, some employer-based and some individually purchased. The U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (U.S. CMS, n.d.) define a high deductible health plan as “a plan with a higher deductible than a traditional insurance plan” (para. 1). With a high deductible plan, the monthly premiums are lower, but the beneficiary pays a large amount of the healthcare costs before the insurance company pays for any of the healthcare costs. “For 2020, the IRS defines a high deductible health plan as any plan with a deductible of at least $1400 for an individual or $2800 for a family” and limits “total yearly out-of- pocket expenses (deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance) to $6,900 for an individual or $13,800 for a family,” if using in-network services only (receiving services outside of the insurance’s approved providers would result in higher costs to the individual and/or family) (U.S. CMS, n.d., para 3).

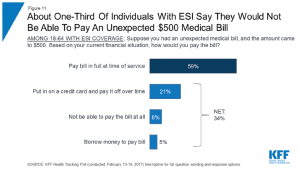

The 2018 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) indicated that the numbers of individuals with high deductible health plans increased from 43.7% in 2017 to 45.8% in 2018 for persons under the age of 65 (Cohen et al., 2019). Moreover, according to Kirzinger et al. (2019), surmising the results of several Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) healthcare tracking polls suggested that about one-fourth of insured workers were required to pay an increased deductible averaging 212% over the last decade, resulting in an approximate deductible of $2000 or more for a single person. Having a high deductible where out of pocket costs must be paid prior to the insurance covering prescription drugs or medical costs may deter individuals from seeking healthcare. Kirzinger et al. (2019) described one KFF 2018 poll where results indicated that 34% of insured adults found it difficult to pay health insurance deductibles, 28% found it difficult to pay monthly premiums for health insurance, and 24% found it difficult to pay the co-pays for health-related costs, such as visits to a physician’s office and prescription medications. Another KFF poll, performed in 2017, (Kirzinger et al., 2019), presented a scenario to those with employee-sponsored insurance (ESI) asking them if they had to pay $500 of an unexpected healthcare bill, would they be able to pay the bill. Fifty-nine percent said they would be able to pay the bill at the time of service, whereas 34% said they would not and would need to use a credit card, borrow money, or not be able to pay it at all. The results of this 2017 poll is depicted in Figure 3.4.

Attribution: Kaiser Family Foundation

License: © Kaiser Family Foundation. Used with permission.

For those with public health insurance (Medicare or Medicaid), Medicaid does not pay hospitals or physicians the same rate as Medicare. Medicare does not pay the same as most private health insurance plans. Original Medicare does not provide the supplemental benefits that Medicare Advantage does. Medicare Part D has cost limits for medications. Therefore, one may have insurance, but the insurance may not be enough to obtain needed services or may not pay sufficiently to prevent exorbitant costs to the individual. Moreover, healthcare providers cannot depend on third parties to reliably provide any, or even some, form of payments (Elrod & Fortenberry, 2017).

Not Having a “Usual” Place to Obtain Healthcare One of the questions on the 2018 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) asked whether interviewees (249,456 individuals 18 years and older) had a usual place of healthcare (Cohen et al., 2019). Having a usual place of obtaining healthcare often involves having an easily accessible location with appropriate services provided and development of a rapport with caregivers. Interview results indicate that among adults aged 18 and over, 85% have a usual place of healthcare. The most often-cited place for healthcare was a doctor’s office or HMO (69.7%), followed by clinic or health center (26.1%), hospital outpatient department (1.5%), hospital emergency room (1.4%), and some other place (1.3%). Specific variables that may affect having a usual place of healthcare identified in the 2018 NHIS are gender, race and ethnicity, education, employment, poverty level, and not having insurance. See results of these variables from the 2018 NHIS (CDC, n.d.) in Table 8.1.

Table 3.1: CDC Summary Health Statistics: National Health Interview Survey, 2018, Adults 18 and Over |

|

| Do you have a usual place of obtaining healthcare: Yes or No? | |

| Yes | 85% |

| No | 15% |

| Race/ethnicity and gender combined | Percentage having a usual place of healthcare |

| White females | 90.80% |

| Black female 8 | 8.80% |

| Hispanic or Latino female | 84.90% |

| White male | 83.60% |

| Black male | 81.90% |

| Hispanic or Latino males | 73.90% |

| Education level | Percentage having a usual place of healthcare |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 90.1% |

| No high school diploma | 79.1% |

| Current Employment | Percentage having a usual place of healthcare |

| Have worked full-time; may be unemployed at this time | 85.60% |

| Work part-time | 83.80% |

| Poverty status | Percentage having a usual place of healthcare |

| Below poverty threshold | 79.60% |

| Near poor (income 100% to less than 200% of poverty level) | 79.70% |

| Not poor (incomes higher than 200% of poverty threshold or greater) | 87.80% |

| Uninsured | Percentage having a usual place of healthcare |

| Yes | 51.50% |

| No | 48.50% |

| Attribution: Deanna Howe License: CC BY-SA 4.0 |

|

Timeliness of Obtaining an Appointment or Treatment

Sometimes individuals cannot receive an appointment with a healthcare provider as quickly as needed or desired. This causes a delay in treatment and possible worsening of symptoms. Many individuals end up in the emergency department or outpatient clinic, and higher costs may be incurred or poorer health outcomes may result from delays. Long waits in physician’s offices or in emergency departments is another barrier to healthcare (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [IDPHP], 2019a). Patients may leave without being seen if the wait is long, thus delaying care further. Patient dissatisfaction may occur also. Often, tests are ordered and there is a delay in obtaining those services. The delay may lead to distraught feelings, development or extension of complications requiring hospitalization and possible poor health outcomes, and likely increased costs (ODPHP, 2019a).

Language Barrier

The number of individuals in the U.S. with English as a second language is increasing (Meuter et al. 2015), posing a language barrier issue between non- English speaking patients and healthcare workers. A language barrier prevents ideal communication between the patient and the healthcare provider, with possible errors in assessment of problems, services rendered, and in care instructions. A lack of culturally-competent care may also be present if the healthcare provider is not aware of, or chooses not to be aware of, cultural differences that affect the communication between patient and healthcare provider. A lack of culturally- competent care may lead to inequitable care for those who cannot speak English fluently (Meuter et al., 2015).

Pause and Reflect

How might a language barrier affect seeking healthcare?

Consider if you were visiting a different country whose people speak a different language. What if you become ill?

How would you find healthcare?

How would you communicate the problem?

Health Literacy

The official definition of health literacy from the HHS (2020b) is “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information needed to make appropriate health decisions” (para. 1). Navigating the healthcare system may be difficult if an individual is not aware of what steps need to be taken and where to go for assistance. Without health literacy skills, individuals do not have the knowledge of where and how to obtain healthcare services or navigate the complex U.S. healthcare system. Reading and comprehending health resources may be a challenge. The World Health Organization (WHO) (1998) characterizes health literacy as overall encompassing of what is needed for healthcare services to be accessed and utilized by an individual: health literacy implies the achievement of a level of knowledge, personal skills and confidence to take action to improve personal and community health by changing personal lifestyles and living conditions. Thus, health literacy means more than being able to read pamphlets and make appointments. By improving people’s access to health information—and their capacity to use it effectively—health literacy is critical to empowerment. Health literacy itself depends upon more general levels of literacy. Poor literacy can affect people’s health directly by limiting their personal, social, and cultural development, as well as hindering the development of health literacy (p. 10). In addition, making healthcare decisions and taking responsibility for self-care are also concerns for those who have low health literacy skills (CDC, 2019j). According to Hickey et al. (2018), characteristics associated with low health literacy are those with lower income levels, limited education, chronic diseases, older age, and non-native English speakers (p. 49). Significantly, however, healthcare providers may not be able to tell from looking at a person which level health literacy they have. Therefore, it is important to assume every patient needs careful instruction and an assessment of understanding because lower health literacy levels can adversely affect healthcare-seeking behaviors, such as understanding of instructions, importance of following directions, and follow-up care.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2015) encourages healthcare organizations to develop quality improvement measures to make information simple to comprehend and healthcare systems easy to maneuver. Hickey et al. (2018), recommend incorporating health literacy into the standard clinical care for all patients. Some easy suggestions include the following:

- Use plain language—organize the information, break up complex information, define technical or medical terms with simple language

- Use visual aids—illustrations, simple drawings, clear labels

- Use technology—patient portals, telemedicine, mobile apps

- Use effective teaching methods—open-ended questions, “teach-back” communication method, “show back” to demonstrate skills (ACP, 2019)

Pause and Reflect

A non-native English speaker is about to be discharged from the hospital following surgical removal of the appendix. The nurse comes into the room and discusses the need for proper care of the surgical wound, to continue taking all the antibiotic medications provided, and to call the primary doctor if there are any complications (excess pain, fever, draining from surgical site). The nurse asks if the patient understands the directions and they nod their head in the affirmative. The patient is asked to sign the form, given the written discharge instructions, and discharged to home. In this scenario, how do we know the patient understood the instructions?

Health Disparities

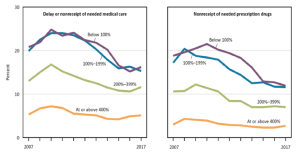

Orgera and Artiga (2018) define health and healthcare disparities as “differences in health and healthcare between population groups” (para.1). Various factors, such socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, age, disability status, and regions of the nation, may affect the care individuals receive. We have already discussed reasons an individual may not seek healthcare and/or delay care and the costs associated with health insurance. Arguably, some variables consistently indicate there are some groups who receive less healthcare. The U.S. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP, 2019a) states that those in a lower socioeconomic status receive less healthcare. And many persons in the poor and near-poor categories, according to the research presented here, delay healthcare or have difficulty with the costs of healthcare. One should note that many poor do receive Medicaid. However, as stated previously, Medicaid may not be accepted by all physicians. Delving deeper into the unmet healthcare needs of persons based on poverty levels, the NCHS (2019) compared unmet (delayed or received) healthcare needs due to costs in persons based on national poverty levels from 2017 to results obtained in 2007 (based on data from the 2017 NHIS previously discussed). The poverty levels compared were the same as previously discussed elsewhere (below poverty level; nearly poor: 100–199% of poverty level) except two groups of not-poor were established: the first group of not-poor lived at 200–399% of the poverty level, and the next group of not-poor lived at or above 400% of the poverty level. Results indicated that although there has been improvement in meeting the medical needs in all groups since 2007, a divide remains between the percentage of unmet medical needs of the poor and those in the not-poor groups because of costs. Thus, those in the poor groups have unmet healthcare needs, and, as greater levels of poverty were identified, the discrepancy increased incrementally. The NCHS (2019) also interviewed these same individuals in the 18–64 age group to determine if they received needed prescription medications. Again, despite the vast improvements in the last decade, there remains a difference in the poor, near-poor, and not-poor categories (Figure 3.5).

Source: Health, United States 2018

Attribution: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

License: Public Domain

Geographic Location

Geographic location is another factor that may affect whether individuals receive healthcare (NCHS, 2019). Individuals in rural areas receive less healthcare access and utilization than those in urban areas. Of all children aged 19–35 months in the U.S. in 2017, 29.6% did not receive adequate vaccination coverage. Children living in rural areas received the appropriate vaccination less than their urban counterparts (66.8% compared to 71.9%, respectively) (NCHS) (Figure 3.6).

NOTES: MSA is a metropolitan statistical area.

Source: Health, United States 2018

Attribution: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

License: Public Domain

Health Access for Illegal Immigrants

Many variables have already been discussed about why different persons or populations delay seeking healthcare or possibly receive inadequate healthcare. Illegal immigrants have unique health concerns as they may be mentally and physically vulnerable. Specific concerns for this population may be sex trafficking and lack of vaccinations, also. However, fear of exposing their residency status may be the primary concern of undocumented individuals and may explain why they delay or do not seek healthcare. Language or other cultural barriers may be an issue when receiving needed healthcare for this population. Only some communities have clinics to address health needs of undocumented persons seeking care and include translation services as needed. Also, some health departments are available that provide childhood vaccinations and other health education services to undocumented families. For emergency situations, individuals could seek care in emergency rooms. Regardless of the legality of citizenship, no person is turned down in the U.S. emergency departments for healthcare.

3.6 CONSEQUENCES OF INADEQUATE ACCESS TO HEALTHCARE

Individuals without access to healthcare overall, are likely to have poorer health and quality of life (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2019a). Individuals without access to healthcare are more likely to encounter increased healthcare costs to self and family and to society (ODPHP, 2019a). They are less likely to participate in preventive health measures and obtain needed healthcare services in a timely manner (ODPHP, 2019a). They are more likely to seek healthcare in emergency departments and outpatient clinics and be hospitalized for avoidable illnesses (ODPHP, 2019a). And, they are more likely to live with chronic conditions and succumb to complications prematurely (ODPHP, 2019a).

3.7 EMERGING ISSUES AND POSSIBLE IMPROVEMENTS IN THE HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

Through the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, the federal government each decade develops initiatives striving for improved health for every American (ODPHP, 2020). Currently, Healthy People 2030 objectives are being formulated, while the 2020 objectives are being analyzed. The public may attend any committee meeting. Other emerging noteworthy issues are the COVID-19 virus, illegal immigration, numbers and availability of healthcare providers and work models used, telehealth, and lack of use of evidence-based preventive services.

Healthy People 2020

The Healthy People 2020 objectives (ODPHP, 2019b) and corresponding findings are as follows:

- Increase the proportion of persons with health insurance.

- 2020 Goal: 100% (83.2% in 2008) (90.6% in 2018 [Cohen et al., 2019])

- Increase the number of persons with a usual primary care provider.

- 2020 Goal: 83.9% (76.3% in 2007) (85.4% in 2018 [Cohen et al., 2019])

- (Developmental) Increase the number of practicing primary care providers.

- Increase the proportion of persons who have a specific source of ongoing care.

- 2020 Goal: 95% (86.4% in 2008)

- Reduce the proportion of persons who are unable to obtain or who delay in obtaining necessary medical care, dental care, or prescription medicines.

- 2020 Goal: 4.2% (4.7% in 2007) (4.4% did not receive medical care due to cost, and 6.3% delayed seeking medical care in 2018 [Cohen et al.); 11.9% did not receive their prescription medicines in 2017 (NCHS, 2019)

- (Developmental) Increase the proportion of persons who receive appropriate evidence-based clinical preventive services.

- (Developmental) Increase the proportion of persons who have access to rapidly-responding prehospital emergency medical services.

- Reduce the proportion of hospital emergency department visits in which the wait time to see an emergency department clinician exceeds the recommended time frame.

Numbers and Availability of Healthcare Providers and Work Models

Used Shortages of healthcare providers, specifically primary care providers, will continue (Institute of Medicine, 2015). New methods of scheduling patients and utilizing resources may need to be addressed. Better utilization of resources might meet the access needs and reduce delays in care. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) describes one issue with access due to a supply-demand mismatch: scheduling and wait times. Any imbalance, or mismatch, with what is needed in terms of healthcare services and what is available in terms of those services results in delays in receiving care and may cause patients to not seek healthcare services or seek services elsewhere. Other issues may be office culture, operational inefficiencies and inadequate or underuse of resources (IOM, 2015). All healthcare providers need to switch to a patient-centered approach to care as opposed to the provider-centered method of the past (IOM, 2015). A patient-centered approach may mean having providers available for walk-in appointments—where the patients don’t have to have an appointment—as done in retail clinics. Providers scheduling later office hours and weekends so that individuals might be able to see their regular healthcare provider also promotes a patient-centered approach. National benchmarks should be evaluated by practitioners to help identify factors that would more closely align their practice with patient-centered care and respect for patients’ time. One benchmark offered by the IOM (2015) is evaluating wait times for all healthcare provider’s office visits. The IOM also suggests evaluating driving times for patients to doctor’s visits.

Telehealth Increasing Access to Care

Telehealth (communication through phone or video), also known as telemedicine, may be a useful resource in a physician practice. According to the IOM (2015), up to 25% of patients call the physician’s office on any given day, and the use of telehealth could curtail an office visit. Utilizing nurses and advanced- practice professionals to help with providing care, health teaching and preventive management, informatics managers, and coordinators of care should be evaluated. The COVID-19 outbreak may have changed telehealth forever. The Centers for

Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) have relaxed the rules for payment to healthcare providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telehealth waivers (for both video and phone) from CMS during this national crisis include allowing healthcare providers to perform telehealth visits in rural and non-rural areas, cross state lines, care for established and non-established patients, and bill the same as if the visit were in person (HHS, 2020). Also covered are emergency department visits, initial nursing facility and discharge visits, home visits, and therapy visits. Federally

Qualified Health Centers and Rural Health Clinics have also been added to provide telehealth sites at a distance or to arrange telehealth services for those unable to travel (HHS, 2020), thereby possibly reaching those who are disadvantaged. With the use of telehealth expansion, especially for Federally Qualified Health Centers and Rural Health Clinics during COVID-19, hopefully payment for these services can continue so that all persons can easily access a healthcare provider and in a timely manner.

3.8 SUMMARY

This chapter discussed variables and statistics related to access to healthcare, barriers of access and utilization of healthcare services, problems associated with lack of access, and possible measures going forward. Considering the statistics provided, the factors associated with increased access to healthcare, seeking care when needed, and not delaying seeking healthcare are: higher educational levels, higher family income levels, and having healthcare insurance. Whether other variables affect health and better outcomes is debatable, considering the statistics provided, and should continue to be evaluated. Perhaps healthcare providers need education and training to identify their own biases to ensure equitable care for all racial and ethnic cultures.

3.9 REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. What does access to healthcare mean?

2. Discuss three barriers to adequate healthcare.

3. What does it mean to be health literate?

4. Describe two specific ways to improve access to healthcare.