Chapter Six – Myth & The Hero

Andy Gurevich

This week, we will be exploring the role of the hero in mythic contexts. Not all heroes look or act alike, and it will be important to explore the many ways we look to each other for help, rescue, and salvation.

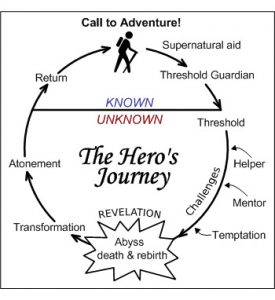

We will begin at the beginning, and explore the very first hero story ever written. Or at least, the earliest surviving example of one. Gilgamesh is a great story; it has all the makings of a typical hero myth. Joseph Campbell briefly outlines the hero quest:

- The call to the quest–the hero consciously seeks the quest. In Gilgamesh, he seeks immortality. In another variation, the quest is thrust upon the hero—he or she may wander into a woods or area that is magical or strange and dangerous and have to navigate the dangers to return.

- The going out–the hero ventures out on the quest. There often are “helpers” along the way. Gilgamesh, in his first quest to kill Humbaba, has the help of Enkidu and other men, and the god Samash.

- Fulfillment of the quest–after a series of tests or challenges, the hero completes the quest.

- Return–the hero return with a great gift or boon for his people. It may be a physical item like gold or a magical object, or it may be some great knowledge that will aid his people. (Moses is a great example—his return with the Ten Commandments set up the principles for a new society.)

- The hero undergoes tests that change him, usually for the good. We can see the pattern in the lives of Buddha, Mohammed, and Jesus.

Here is a chart of the hero’s journey based on the works of Joseph Campbell:

Reading:

- Please read:

- Please watch:

I hope you enjoy it! Things to look for as you read:

- The early character of Gilgamesh—does he change in the end?

- The symbolic role of Enkidu—what does he represent in the story?

- The two quests—what is each one’s purpose and are they fulfilled?

- The second quest is nicely done up in archetypes. What are some of the archetypes?

- Is Gilgamesh a hero a modern audience can relate to? (Check out Wikipedia: Gilgamesh in Popular Culture.)

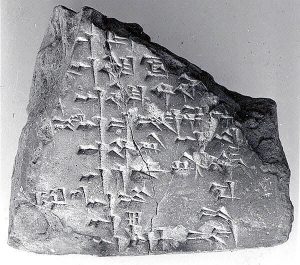

The story was one of the first written narratives, written in Cuneiform, a series of wedges pressed into wet clay. Unfortunately, these clay tablets break easily. There were also different versions; stories of Gilgamesh were found scattered throughout the region of what is now modern Iran, Iraq, and Turkey.

Scholars have pieced together the story as best they can, although we still have questions about certain events. For example, when Gilgamesh goes to find Urshanabi to take him across the Waters of Death, Gilgamesh smashes the sacred statues. We don’t know what their purpose was or why Gilgamesh smashed them.

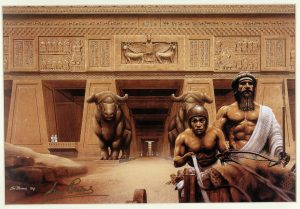

Gilgamesh goes on two journeys. His first is a physical quest-to kill Humbaba and bring cedar back to Uruk. He succeeds at both.

His second quest is a spiritual or intellectual quest. He seeks immortality after the loss of his friend Enkidu.

Look at the two challenges he faces: he must go through the 36 mile tunnel, suggesting death. When he exits the tunnel, he is in an orchard with trees which bore jewels. He was convinced he was in the garden of the gods. Then he must cross the Waters of Death. He meets with Utanapishtim, but is told he cannot have immortality.

So Gilgamesh fails to gain immortality. He is given a consolation prize of sorts. If he can dive deep into the waters (what’s the symbolism here?) he can gather a plant which will endow him with everlasting youth. He loses his plant to a snake (more symbolism), who immediately sheds its skin. Gilgamesh has failed in his journey. Or has he? What does Gilgamesh gain? What does he take back to his people? Does the experience change him?