6.5 Correcting the Final

Preview

This section of Ch. 6 will cover the following topics:

- editing for grammar, usage, and punctuation

- formatting

- peer editing

- using feedback

Readers do not notice correct spelling, but they notice misspellings. They look past your sentences to get to your ideas, unless the sentences are awkward and poorly constructed. They do not cheer when you use “there,” “their,” and “they’re” correctly, but they notice when you do not. Readers (including teachers, bosses, and customers) are impressed by an error-free document.

The first chapters of this book will help you eliminate mechanical errors in your writing. Track which topics you master and which you still don’t understand, then keep working on the ones that challenge you. Do not hesitate to ask for help from your instructor, peer editors, or the college tutors.

Step 5: Editing

The final step after revising content is editing. When you edit, you examine the mechanical parts of the paper: spelling, grammar, punctuation, and formatting. The goal of editing is correctness.

Do not begin editing until you are sure the content is complete. Then, do your first round of edits on the computer so you can fix problems as you go. But always do a final read-through on the printed page; you will see things you miss on the computer.

Look for problems you know you have, as well as the following common errors:

- Check capitalization and punctuation, especially commas, apostrophes, quotation marks, and italics.

- Use words correctly. Avoid clichés and generalizations. Don’t use “you.”

- Be sure sentences are complete, no run-ons or fragments.

- Look for common grammar problems, including parallel structure, pronoun errors, subject-verb agreement, misplaced or dangling modifiers, and verb tense consistency.

- Run a spellcheck, but double check to be sure it hasn’t overlooked words.

Formatting

Write your documents in Word (the college will provide you with Word for free, if you don’t already have it). Many teachers will also want you to submit your final document as a PDF. If you don’t know how to do this, contact the computer lab at the college.

The format of a document is how it is laid out, what it looks like. An instructor or a department will often require students to follow a specific formatting style. The most common are APA (American Psychological Association) and MLA (Modern Language Association). Guides like Diana Hacker’s A Pocket Style Manual and websites like the Purdue Online Writing Lab can help you understand formatting. Following is a brief overview.

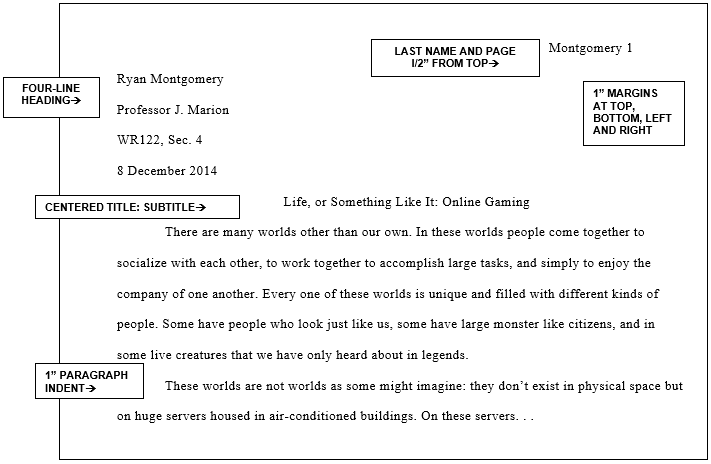

This is an example of MLA formatting (commonly used in writing classes):

Here is a description of the formatting above:

- Use standard-sized paper (8.5” x 11”).

- Double-space all of the paper, from the heading through the last page.

- Set the document margins to 1” on all sides.

- Do not use a title page unless requested by your instructor.

- Create a running header with your last name and the page number in the upper right-hand corner, 1” from the top and aligned with the right margin. Number all pages consecutively.

- List your name, the instructor’s name and title, the course name and section, and the due date in the heading on the top left of the first page only. (Notice the date is written in day, month, year order.)

- Center the essay title on the next line below the heading. Follow the rules on capitalization in Ch. 3. Do not increase font size, use bold, or underline.

- Begin the paper below the title. No extra spaces.

- Indent paragraphs 1” from the left margin.

Proofreading requires patience; it is very easy to miss a mistake. Wait at least a day after you have finished revising to proofread. Some professional proofreaders read a text backward (the last paragraph, then the one before that, and so on) so they can concentrate on mechanics rather than being distracted by content.

Editing takes time, but the benefits can be seen in the quality of your work, the response of your readers, and the grade you earn.

Peer Editing

After working closely with a piece of writing, we need to step back and show our work to someone who can give us an honest response about its strengths and weaknesses. Every professional writer does this. Every student writer would benefit from doing this.

An editor is your first real audience. This is your opportunity to learn what confuses and delights a reader so you can fix problems before sharing the final draft with a wider audience (and the teacher).

The best editors for students are other students in the same class. A college instructor rarely has time to go over drafts in detail with students. Your mom and your best friend aren’t going to say anything bad. Even a tutor, though helpful, is only going to give you one opinion. But a small group of students who are working on (maybe struggling with) the same assignment, who are learning the same information, and who are as invested as you are in succeeding is a perfect group to give helpful feedback.

How many peer editors do you need? Three or four is plenty. Fewer, and you will have a hard time separating subjective reactions from objective advice. More, and you will just get duplicate information.

“Peer editing” is not just asking someone for feedback. You should trade papers and edit their work as they edit yours. Trading papers has a hidden benefit: the best way to become a good editor of your own writing is to practice editing someone else’s work. It is much easier to see problems in someone else’s writing, but also your editing “muscles” get exercised and trained. You will learn almost as much from doing a peer edit as you will from getting one.

Guidelines for Peer Editing

The purpose of peer editing is to receive constructive criticism, not just compliments. You may be uncomfortable sharing your writing at first, but you’ll find it gets easier and the value is immeasurable.

Becoming a good editor does not happen spontaneously; it is a skill that has to be learned and practiced. But the more you do it, the better you get at it.

Our initial tendency may be to say only what is wrong with the work, to praise it excessively, to remain silent, to argue every point, or to say what we think the writer wants to hear. Try to avoid those pitfalls.

The following guidelines will help you become a better editor and a better writer.

First, as the writer

When you give your essay to a reader for peer editing, you are saying, “I think I am finished. Do you see any problems I have missed?”

- Don’t apologize for how bad or unworthy it is. (If it’s that bad, it isn’t ready for peer editing.)

- Don’t explain your intention; it should be clear. In fact, it can be helpful to ask your editor to tell you what they think your intention is.

- You may ask a reader to pay particular attention to something that has caused you problems.

- Otherwise, just say, “Thank you” and let go.

Then, as the reader

- Be respectful. Don’t criticize in a way that makes a writer feel stupid. Believe in the possibilities of the essay. Avoid sweeping judgments (“this is good,” “this is bad”); if you can’t say why, the writer won’t know what to do. Give specific input (“I can’t find a thesis,” “The transitions were easy to follow.”) Avoid the word “you”; talk about the essay, not the writer.

- Try to say positive things as well as suggesting changes. It is helpful for writers to know what is working as well as what is not working.

- Write on the essay. In fact, write all over it!

- Read the essay at least twice. The first time, get familiar with the topic and do a little light commentary. Maybe note errors in mechanics.

- Then, go over the essay a second time. Look deeper. Consider organization, clarity, and writing quality. Note anything that confuses you, interests you, or bores you. At the very least, answer the following questions. But don’t hesitate to offer other thoughts that will help the writer achieve her purpose.

- Is the formatting correct?

- Is the title interesting?

- Is the introductory paragraph engaging and does it indicate the direction of the paper?

- Is the thesis clear and specific?

- Does the body of the essay develop and support the main idea?

- Are transitions clear?

- Does the essay include extra, unnecessary material, or is more detail needed? If so, where?

- Does the conclusion feel meaningful?

- Finally, answer these two questions. Every writer needs to hear something good, but nobody ever produces a perfect document on a first try.

- What one thing most needs to be improved in this essay?

- What one thing did you like best or remember most clearly?

Lastly, as the writer again

After your essay has been critiqued, read the input you receive.

- If you don’t understand a comment, ask the editor to clarify. But it is unnecessary to debate a point or explain yourself.

- If the mechanical suggestions are correct, make those changes. Always double check; do not simply take an editor’s word for a grammar or punctuation rule!

- Decide which suggestions on the content will improve your essay and which will not. Incorporate the ideas you like. If several readers note the same problem, take the advice seriously. However, you are always the final judge about what you do in your own essay.

Using Tutors

The best time to get help from a tutor is…any time. Tutors can help in the writing process if you are struggling. They can help by going over your draft with you so you give peer editor a more polished version. They can help after peer editing by providing feedback on changes you’ve made. They can also help with any overall grammar or mechanical problems.

What they won’t do is fix your paper for you. Don’t expect that. But they will help you fix your paper. And the one-on-one support can be invaluable.

Exercise 1

Once you are confident the content of your essay is solid, edit it.

A writer is responsible for their own writing. Go through the document yourself, checking formatting, grammar, punctuation, capitalization, sentence structure. Run a spellcheck.

If you need additional help, put a peer editing group together or go to a tutor.

When you have finished editing your essay, respond to the following in your notebook:

- Identify two things you changed or fixed in revising your essay. Be specific. Don’t just say, “It is clearer.” Instead, explain how you revised your conclusion so it was stronger or how you added more detail to one of the body paragraphs.

- Identify two things you changed or fixed in editing your essay. Be specific. Don’t just say, “I checked the grammar.” Explain how you identified and corrected fragments and run-ons or checked to be sure verb tense was consistent or fixed formatting problems you had on earlier assignments.

Am I Done?

The writing process is “recursive.” That means you can repeat steps at any point if you need to do so. If you start drafting and realize your thesis needs to be clearer, go back and work on Step 2 again. If you are in the middle of revising and think a paragraph needs more detail, do a quick prewrite to see what other details you can discover.

When should you consider your essay finished? Donald Murray wrote this in his essay about revising called “The Maker’s Eye”:

“A piece of writing is never finished. It is delivered to a deadline.”

The best writers always have an urge to keep tinkering. If you give yourself enough time to work through this process, however, you WILL reach a point where you have a good product, and you will do so before the assignment is due.

Takeaways

- Peer editing is a skill that improves with practice.

- Providing a peer edit requires you to be respectful, thorough, and specific.

- Tutors can provide invaluable one-on-one support at any point in the process.

- Using feedback from peer editors requires you to be open to input but also able to identify what will help you achieve your purpose.

- If you use this writing process, your final document will be much better than it would have been otherwise.

examining writing carefully to find and correct mechanical errors such as spelling, grammar, punctuation, and typing errors

based on personal taste or opinion

not influenced by personal feelings

useful, helpful