49 The Making of Aluminum

Aluminum is the most abundant metallic element in the Earth’s crust, but it is rarely found in its elemental state.

In 1825 Hans Christian Oersted, a Danish chemist, had extracted tiny amounts of aluminum powder from alum (aluminum potassium sulfate mined from the earth). He was the first person to do so. However, aluminum making was not an economical process until 1889 when American, Charles Martin Hall, patented an inexpensive method (below) for the production of aluminum, which brought the metal into wide commercial use.

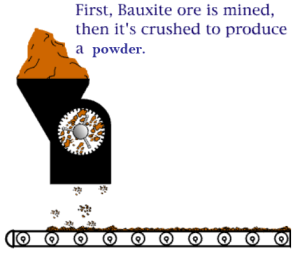

The process of making aluminum is quite long and complicated. It occurs in many minerals, but its primary commercial source is bauxite, a mixture of hydrated aluminum oxides and compounds of other elements such as iron.

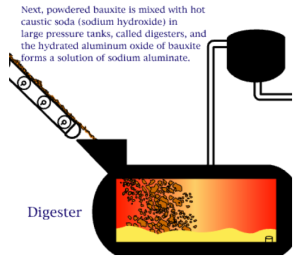

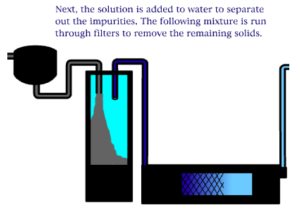

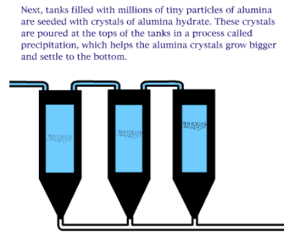

An electro chemical process known as the Bayer process is used to make aluminum. Aluminum is made primarily of bauxite ore found in many regions of the world. The ore is crushed and ground into a fine powder that is chemically treated so that it can re-solidify in the appropriate composition. The final step of the process is to melt the solidified mixture through an electrolytic process. Note that the resultant aluminum is rarely used in its pure form and is often alloyed with silicon, magnesium, or other alloying elements.

The Bayer process is the principal industrial means of refining bauxite to produce alumina (aluminum oxide) and was developed by Carl Josef Bayer. Bauxite, the most important ore of aluminum, contains only 30–60% aluminum oxide (Al2O3), the rest being a mixture of silica, various iron oxides, and titanium dioxide. The aluminum oxide must be further purified before it can be refined into aluminum metal.

The Bayer process is also the main source of gallium as a byproduct despite low extraction yields.

Prior to the Hall–Héroult process, elemental aluminum was made by heating ore along with elemental sodium or potassium in a vacuum. The method was complicated and consumed materials that were in themselves expensive at that time. This meant that the cost to produce the small amount of aluminum made in the early 19th century was very high, higher than for gold or platinum! Bars of aluminum were exhibited alongside the French crown jewels at the Exposition Universelle of 1855, and Emperor Napoleon III of France was said to have reserved his few sets of aluminum dinner plates and eating utensils for his most honored guests.

Production costs using older methods did come down, but when aluminum was selected as the material for the cap/lightning rod to sit atop the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., it was still more expensive than silver.

The Hall–Héroult process was invented independently and almost simultaneously in 1886 by the American chemist Charles Martin Hall and by the Frenchman Paul Héroult—both 22 years old. In 1888, Hall opened the first large-scale aluminum production plant in Pittsburgh. It later became the Alcoa corporation.

The Hall–Héroult process is the major industrial process for smelting aluminum. It involves dissolving aluminium oxide (alumina) (obtained most often from bauxite, aluminum’s chief ore, through the Bayer process) in molten cryolite and electrolyzing the molten salt bath, typically in a purpose-built cell. The Hall–Héroult process applied at industrial scale happens at 940–980 °C (1700 to 1800°F) and produces 99.5–99.8% pure aluminum. Recycling aluminum requires no electrolysis, thus it is not treated in this way.

Because Hall–Héroult processing consumes copious electrical energy and its electrolysis stage can create large amounts of carbon dioxide if the power is not produced in a low emission way. The process also produces fluorocarbon compounds as byproducts; therefore it can contribute to air pollution as well as climate change.

Aluminum produced via the Hall–Héroult process, in combination with cheaper electric power, helped make aluminum (and incidentally magnesium) an inexpensive commodity rather than a precious metal. Aluminum is not useful in its pure state so it must be alloyed with magnesium and one or more of the following elements: copper, silicon, manganese, chromium.

This, in turn, helped make it possible for pioneers like Hugo Junkers to utilize aluminum and aluminum-magnesium alloys to make items like metal airplanes by the thousands, or Howard Lund to make aluminum fishing boats.

In 2012 it was estimated that 12.7 tons of CO2 emissions are generated per ton of aluminum produced.

Aluminum is a very common material in the aerospace industry and, as such, it finds its way into the machine shop just as often as steel.

Videos

Watch this full-length 43:31 full episode of Modern Marvels: How Aluminum Built the Modern World (S13, E26) | Full Episode | History – YouTube by History, January 8, 2022.

Watch this 16:57 modern video Aluminum Mining: Inside the World’s Largest Aluminum Deposits: Mining & Manufacturing by Lord Gizmo, March 14, 2024.

Watch this 6:12 historical video about the adoption and suitability of aluminum for aircraft. Aluminium – The Material That Changed The World by Real Engineering, August 24, 2016.

Derived from Bayer process – Wikipedia and Hall–Héroult process – Wikipedia access and available 6 December 2024 and The Virtual Machine Shop http://www.jjjtrain.com/vms/eng_metallurgy/eng_metallurgy_14.html retrieved from the Wayback Machine 16 January 2024.