- Bertman, S. Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Bottéro, J. Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

- Brosius, M. Women in Ancient Persia, 559-331 BC . Clarendon Press, 1998.

- Culbertson, Laura. “Slaves and Households in the Near East.” Oriental Institute of Chicago, 2010, pp. 101-112.

- Halton, C. &Svärd, S. Women’s Writing of Ancient Mesopotamia. Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Kramer, S. N. The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998.

- Kriwaczek, P. Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. Thomas Dunne Books, 2010.

- Leick, G. The A to Z of Mesopotamia . Scarecrow Press, 2010.

- Nemet-Nejat, K. R. Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Greenwood, 1998.

- Spencer, C. Homosexuality in History. Harcourt, 1996.

1 The Neolithic Revolution and Women in Early Civilizations

Introduction

The Ice Age, the Pleistocene, came to a gradual end between 12, 000 – 10,000 years ago ushering in a new climatic era: the Holocene. That climate shift was accompanied by a massive changes in human society. After at least 100,000 years of foraging and hunter/gathering subsistence (the Paleolithic (Old Stone) Age, some groups in some places began settling down. They domesticated plants and animals more extensively and established larger permanent settlements. These changes created a cascading series of dramatic iimpacts on human relationships, humans lived environment and technology, and has been called the Neolithic (New Stone) Revolution. Among the many profound cultural and social changes were those relating to gender roles in terms of work, family, and power. In this chapter we will examine the Neolithic Revolution, and look at two of the earliest complex civlilizations that were made possible by the agricultural production of the Neolothic Revolution: Ancient Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt.

Focus Questions

What can we know about women’s roles in human societies during the Pleistocene (Ice Age)?

How did women’s roles seem to change during the Neolithic Revolution? Why?

What was women’s status in Ancient Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt? Did the emergence of complex urban cultures chane women’s roles and status significantly? if so, why?

Were their significant differences in women’s roles ans status between Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt? If so, why?

Can you identify patriarchal norms and practices in thes ancient societies?

Give some examples of specific significant women in Ancient Mesopotmia or Egypt.

Agriculture and the Neolithic Revolution

Historian Lauren Ristvet defines agriculture as the “‘domestication’ of plants… causing it to change genetically from its wild ancestor in ways [that make] it more useful to human consumers.”12 She and hundreds of other scholars from Hobbes to Marx have pointed to the Neolithic Revolution, that is, the move from a hunter-gatherer world to an agricultural one, as the root of what we today refer to as civilization. Without agriculture we don’t have empires, written language, factories, universities, or railroads. Despite its importance, much remains unclear about why and where agriculture began. Instead, scholars hold a handful of well-regarded theories about the roots (pun intended) of agriculture.

Most scholars agree that the Ice Age played a fundamental role in the rise of agriculture, in the sense that it was impossible during the much colder and often tundra-covered period of the Pleistocene, but inevitable during the Holocene thawing. Only 4,000 years before the origins of agriculture, the planting of anything would have been an exercise in futility. During the Last Glacial Maximum (24,000 – 16,000 years ago), average temperatures dropped “by as much as 57˚ F near the great ice sheets…”13 This glaciation meant not only that today’s fertile farmlands of Spain or the North American Great Plains were increasingly covered in ice, but also that other areas around the world could not depend on constant temperatures or rainfall from year to year. Pleistocene foragers had to be flexible. The warming trend of the Holocene, by contrast, resulted in consistent rainfall amounts and more predictable temperatures. The warming also altered the habitats of the megafauna that humans hunted, alterations that in some cases contributed to their extinction. Therefore, as animal populations declined, humans were further encouraged to plant and cultivate seeds in newly-thawed soil.

When we start to examine other factors that allowed humans to transition to agriculture, we find that the climate factor looms even larger. For example, agriculture was usually accompanied by sedentarism, but we see communal living and permanent settlements among multiple groups of hunter-gatherers. Homo sapiens had also begun to domesticate animals and plants alike during the Pleistocene. Humans were already being buried alongside dogs as early as 14,000 years ago.14 As we’ll see below, gatherers were developing an increasing taste for grains long before they would abandon a foraging lifestyle. Essentially, humans were ready for agriculture when climate permitted it.

We discuss elsewhere the timing of agriculture’s appearance in all of the continents, but generally speaking by about 8,000 years ago, farmers in West Asia were growing rye, barley, and wheat. In northern China, millet was common 8,500 years ago. In the Americas, the domestication of maize began around 8,000 years ago in Mesoamerica, while at about the same time, Andean residents began cultivating potatoes. Once all of these areas realized agriculture’s potential as a permanent food source, they began to adapt their societies to increase their crop consistency and crop yields. We’ll discuss how agriculture affected societal development below.

First Farmers of West Asia [or the Fertile Crescent]

In later chapters we will discuss Mesopotamia, the area between the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers that agriculture would make the “cradle of civilization.” (See Map 2.1). However, the incubator of Mesopotamian and Fertile Crescent agriculture and cultural patterns dated back to the foragers of the nearby Eastern Mediterranean, thousands of years before. The rye, barley, and wheat in West Asia were first harvested by late Pleistocene foragers called the Kebarans who ground wild wheat and barley into a porridge.15 Kebarans consumed the porridge as part of their broad spectrum diet that also included land mammals, birds, and fish. Advancing into the Holocene we see the “Natufian Adaptation,” where residents of this same area began to see the benefits of sedentary living in a precursor to the advent of agriculture. The Natufians consumed the same rye, barley, and wheat that their Kebaran predecessors had, but because their teeth were well-worn it appears they ate relatively more of it. Having a constant source of these grains enabled their eschewing long hunting or gathering soujourns; instead, the Natufians drew more of their meat from in and around Lake Huleh in modern Israel. Near Lake Huleh was Ain Mallaha, one of the earliest examples of year-round human settlement and an important precursor to sedentary agriculture.

Another permanent settlement in Southwest Asia seems to have been more directly responsible for the decision to actually domesticate grain, rather than simply cultivate wild varieties. Abu Hureya in Syria was deeply affected by the Younger Dryas event of 11,000 years ago, an event which caused many of their wild food staples to disappear. Rather than migrating out of the area, the Abu Hureyrans cultivated rye. Soon afterward, other sites in the Levant began to see the planting of barley, while wheat was cultivated in both the Levant and Anatolia.16

First Permanent Settlements in West Asia [of the Fertile Crescent]

The transition from foraging, to collecting to cultivating took place over several centuries, but these gradual changes did serve to mark a very distinct era of permanent settlement during the Neolithic Period. Increased rainfall around 9600 BCE meant that the Jordan River would swell yearly, in the process depositing layers of fertile soil along its banks. This fertile soil allowed locals to rely on agriculture for survival. Soon after they founded Jericho just north of the Dead Sea: “perhaps the very first time in human history that a completely viable population was living in the same place at the same time.”17 By Jericho’s height, around 9000 BCE, the settlement’s population reached the hundreds. This increase cannot be considered an urban boom of course, and the transition away from foraging occurred gradually. For example, excavations from this area have unearthed no separation of tasks or dwellings by gender or skill. However, by the end of Jericho’s development, maintaining large populations in one place would prove to produce other extensive adjustments.18

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=376&height=463)

Jericho’s residents did distinguish themselves from their hunter-gatherer predecessors, however, through their relatively extensive construction projects. They used mud bricks to build a wall that encircled the settlement probably for flood control, a tower, and separate buildings for grain storage.

The former foragers now living at Jericho could rely on fish or other aquatic creatures for meat as they experimented with permanent settlement, but those foragers living further away from large bodies of water would need another source of meat. This need increasingly was met by animal domestication. Domestication would prove to be a slow process, as humans learned the hard way that zebras bite, impalas are claustrophobic, and bighorn sheep do not obey orders. In other words, some animals cannot be domesticated, but this is information only understood through trial and error. By about 7,500 BCE, however, humans in the Taurus and Zagros mountains employed selective breeding to eventually domesticate mountain sheep and goats. The temperament and size of pigs and cows delayed their domestication until the 6,000s BCE, but this process proved equally, if not more important, than that of sheep and goats.

As agriculture and animal domestication progressed, settlements around the Mediterranean became larger and more sophisticated. By 7,000 BCE on the Anatolian plateau, Çatalhüyük reached several thousands of inhabitants. The residents at Çatalhüyük buried their dead, constructed uniform adjacent houses with elaborate designs painted on their interior walls, and had multiple workshops where (among other activities) they wove baskets, and made obsidian mirrors as well as daggers with “carved bone handles.”19 Catalhüyük denizens wove wool into cloth; developed a varied diet of peas, nuts, vegetable oil, apples, honey, and the usual grains; and improved weapons technology with sharper arrows added to their use of daggers and lances. These gains may seem modest by our standards, but the legacy of communal living and, ultimately, political centralization that they introduced was extraordinary.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=810&height=505)

Jericho and Çatalhüyük were surely some of the most notable early settlements, but they were not alone. The appearance of these two settlements was accompanied by the increasing presence of village life across the world. Most early agricultural villages in Southwest Asia and around the world were very similar in appearance; they had around twenty residents and were organized around grain cultivation and storage. Small huts were organized in a “loose circle,” and grain silos were placed between each hut. Labor was a communal activity, and village members all spent time hoeing the fields or hunting. The most valuable asset to a community was the grain itself, but neither it nor the land where it grew it belonged to one individual.

This model existed for hundreds and even thousands of years in some areas, until the villages stopped hunting and domesticated animals. For many scholars, the abandonment of hunting represents the “real” Neolithic Revolution. As communities completely abandoned hunting and gathering, they dedicated more energy to warfare, religion, and construction; in consequence, dwellings and settlements grew, along with a concomitant focus on tool and weapon making.20

Leaving Paleolithic Culture Behind

While the Neolithic Era is described in greater detail elsewhere, it is important to understand Paleolithic and Neolithic differences in order to convey a sense of just how revolutionary the shift to agriculture was for humanity. For example, agriculture contributed to (along with religion and trade) the development of class. Before agriculture, hunter-gatherers divided tasks like seed gathering, grinding, or tool-making. However, without large scale building projects like aqueducts or canals required for agriculture, hierarchies were much less pronounced. The intensification of agriculture during the Neolithic required irrigation, plowing, and terracing, all of which were labor intensive. The amount of labor required could not be met through simple task division; someone had to be in charge. This meant the establishment of ruling elites, a societal grouping that had not existed during the Paleolithic.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=259&height=486)

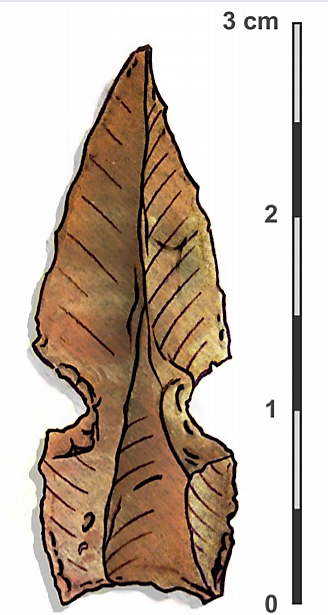

While violence certainly existed during the Paleolithic period, organized warfare was an invention of the Neolithic. Agriculture meant larger populations and settlements that were more tightly packed and closer to one another. These closer quarters created new social and economic pressures that could produce organized violence. Agricultural intensification produced stores of food and valuables that could be seized by neighbors. During the 9,000s BCE, settlements like Jericho began to build defensive walls, while skeletons unearthed in the area reveal wounds from new types of projectiles (like the Khiam Point) developed during the era.21

Family life also changed significantly during the Neolithic. Sedentary communities invested more time and resources into the construction of permanent homes housing nuclear families. People spent less time with the community as a whole and within homes it became easier to accumulate wealth and keep secrets.

The shift in gender roles after agriculture seems to be even more pronounced, as the role of women became more important as humans moved out of the Paleolithic and into the Neolithic era.

During the Paleolithic Era, and until recently in fact, a child would be breastfed until he or she was three or four years old, a necessity preventing mothers from joining long-distance hunting expeditions without their toddlers. However, a breastfeeding woman could complete tasks that “don’t require rapt concentration, are relatively dull and repetitive; they are easily interrupted, don’t place the child in danger, and don’t require the participant to stray far from home.”22 Spinning, weaving, and sewing were some of these tasks. Also, the essential tasks of preparing food and clothing could be accomplished with a nursing toddler nearby. These tasks that may be consigned as “women’s work” today are among the most important tasks (and very time consuming ones before the industrial revolution) that a human could perform. In fact, they were so time consuming that women would spend most of their day on them, often being assisted by men.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=468&height=307)

Over time, Paleolithic women gathered new species of berries as well as bird eggs, and learned which mushrooms were nontoxic. Women also were the principal gatherers of mosses for sleeping mats and other plants for shelter. When men returned with a kill, the women then began an involved process of dressing and butchering it. Sinews from animals and fibers from plants became rope to tie or fasten the hides as well as baskets. Women thus were essential to any kind of productivity or progress associated with hunting. Women used sinews and fibers to create netting for transport and for hunting and fishing. In hunting societies with elements of horticulture, women were responsible for, and could provide, such food as legumes, eggs, and grains. Food gathering and weaving, especially in the dry Mediterranean, was an outdoor and community activity that also served as a preschool and apprentice system for children. So women were also community educators.

Neolithic Women

While Paleolithic women certainly had important responsibilities, the added tasks of herding and animal domestication expanded their roles tremendously in the Neolithic era. Neolithic survival required not only effective food storage, but also increased production. Children on a farm can be more helpful and put in less danger than those on a hunt. Neolithic women increasingly bore more children, either because of increased food production or to help augment it. This increase in child bearing may also have offset an increase in mortality due, for example, to disease. Because dangers from disease grew in new villages due to the ease with which deadly diseases spread in close quarters, and nearby domesticated animals whose diseases spread from animal to humans, more children would be necessary to replace those who had succumbed to illness.

While Neolithic women carried an increased child-bearing responsibility, their other responsibilities did not necessarily wane. Though women may not have fired pottery when it began to appear some 6,000 years ago, they appeared on it in decorative symbols of female fertility. Around 4,000 BCE, gendered tasks shifted again with the domestication of draft animals. Food production once again became men’s domain, as herding was incompatible with childrearing. Later, in Neolithic herding societies, women were often responsible for the actual domestication of feral babies, nursing them and raising them. Men would shear sheep, help weave, market the textiles, and cultivate the food that was prepared in the home.

We should say that this was not the case with all agricultural societies, as many horticulturalists who were able to cultivate crops closer to home were able to remain matrilineal. For example, we have the case of Minoan women on the Mediterranean island of Crete that we discuss in more detail in Chapter Five. On Crete’s hilly terrain, women were able to cultivate terraced horticulture and keep herds of sheep and goats nearby. Therefore, as women lost power and influence elsewhere due to more intensive agriculture, Minoan women actually expanded their control over Crete’s economic and cultural life and would help give rise to Classical Greece.

Toward First Civilizations

We will discuss the Bronze Age elsewhere, but we should mention here that new pursuits like mining added to the domestic burden on women. The advent of the Bronze Age led to far-spread searching and mining for copper and other metals like arsenic or tin to harden it and create the bronze alloy. Mining consequently become a male pursuit. Between 9,000 and 4,000 BCE, as metal become a source for wealth and subsistence, men’s roles shifted from being secondary to being both the food collectors and the economic backbone of individual families and societies.

These Neolithic developments in sedentary agriculture and village life would be the foundation for an explosion of cultural development three thousand years later in Egypt and Mesopotamia (addressed later in this text). By the Age of Exploration in the 1500s CE, most of the world had adopted agriculture as a primary means of subsistence, and the foundation of great civilizations.

Endnotes

12 Ibid., 36.

13 Ibid., 36-37.

14 Chris Scarre, ed. The Human Past: World Prehistory and the Development of Human Societies. 2nd ed. (London: Thames & Hudson, 2009), 183-84.

15 Ristvet, 41.

16 Ristvet, 41-42.

17 Steven Mithen, After the Ice: A Global Human History, 20,000 – 5,000 BC. (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003), 59.

18 Robert Strayer, Ways of the World: A Brief Global History with Sources, 2nd ed (New York, Bedford St. Martins, 2013), 40

19 Mithen, 94.

20 Ristvet, 66.

21 Scarre, 192, 215.

22 Elizabeth Wayland Barber, Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years – Women, Cloth and Society in Early Times, (New York: Norton, 1995), 30.

Women in the first complex civilizations

Explain the transition to complex civilizations from earlier farming societies and how this impacted women’s roles.

Women in Ancient Mesopotamia

by Joshua J. Mark, Encyclopedia of World History

The lives of women in ancient Mesopotamia cannot be characterized as easily as with other civilizations owing to the different cultures over time. Generally speaking, though, Mesopotamian women had significant rights, could own businesses, buy and sell land, live on their own, initiate divorce, and, though officially secondary to men, found ways to assert their autonomy

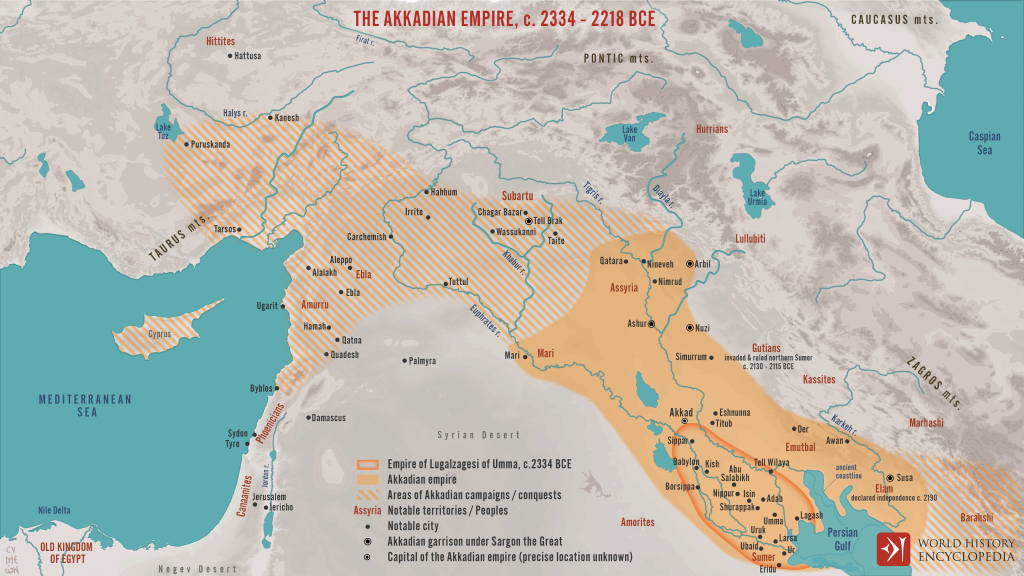

Scholars generally agree that women had the greatest freedoms in the early stages of Mesopotamian cultural development, from the Uruk Period (4100-2900 BCE) through the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) prior to the rise of Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE). It has been noted, however, that Sargon chose a female deity (Inanna/Ishtar) as his protector, installed his daughter Enheduanna (l. 2285-2250 BCE) as high priestess of Ur, and records indicate that women still had many of the same rights as before.

The same claim is made regarding Hammurabi of Babylon (r. 1795-1750 BCE) but, while it is true that worship of female deities and women’s rights declined under his reign, there is still evidence of female autonomy, and this paradigm continues through the period of the Assyrian Empire (c. 1900-612 BCE) and from the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) to the fall of the Sassanian Empire c. 651 CE. Although the patriarchy sought to control women’s rights and personal choices throughout all these eras, women are still recorded as landowners, business owners, administrators, bureaucrats, doctors, scribes, clergy, and in rare cases, even monarchs.

AFTER 651 CE, THERE IS A CLEAR DECLINE IN WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN THE REGION.

Mesopotamian society, like any other, was hierarchical and divided into five classes – nobility, clergy, upper class, lower class, and slaves – and these are sometimes simplified as three designations: free, dependent, and slave. Women’s roles were defined by this hierarchy with elite women at the top and slaves at the bottom. In between was a class of semi-free women, which modern scholars struggle to define clearly, as they were neither completely free nor were they slaves and so ‘dependent’ seems the term that fits best. These women (and men) were usually attached to a temple in some capacity.

Women continued to be defined, more or less, by this hierarchy and maintained their rights until the fall of the Sassanian Empire to the Muslim Arabs in 651 CE. Afterwards, women’s rights declined far more dramatically than any waning under either Sargon or Hammurabi. Some scholars have correlated the decline of women’s status to the rise of male deities and a greater focus on heavily patriarchal religious systems, though this claim has been challenged. Even so, after 651 CE, there is a clear decline in women’s rights in the region.

Women’s Classification

Women were classified according to their social status (as were men) according to the above hierarchy and terms included:

- free women of the nobility/upper class (awilatum in Akkadian)

- free women of the clergy (some known as naditu in Babylonian)

- female administrators (sakintu in the Neo-Assyrian period)

- free women of the lower class (known by various terms)

- prostitutes and/or single women (harimtu in Akkadian)

- dependents who belonged to no male household (sirkus in Babylonian)

- female slaves (amtu in Babylonian)

The names for these classifications changed with the times and different dominant cultures, but the essential hierarchy remained the same. Women were subordinate first to their fathers and then their husbands (with some exceptions such as clergy or certain wealthy nobility), and, later, their sons. Although individual women could manage to pursue their own path, this was rare, and most lived according to the traditions, rules, and expectations of the patriarchy.

Women’s Status & Marriage

Throughout Mesopotamian history, a woman was expected to marry and bear children she would then raise while tending the house. The exception to this is the naditu women of the city of Sippar c. 1880-1550 BCE, who were priestesses dedicated to a male deity. Even these women were expected to marry, though not bear children, and their husbands took secondary wives. The naditu were attached to the household of the temple, performed duties related to the care of the god, and “engaged in business activities” (Leick, 189).

The only term associated with an unmarried woman of marriageable age is harimtu, which, it seems, could refer to a prostitute or a single woman. The precise definition of this term is still debated, but if applied to a single woman, she was either wealthy enough to live by her own rules or a member of the dependent class – neither free nor slave – attached to a temple. According to the scholar Kristin Kleber, these women (or men) were known in Neo-Babylonian communities of the 6th century BCE as sirkus:

Sirkus are often characterized as temple slaves, and it is generally held that their fate was better than that of other kinds of slaves because the temple gods, as owners, did not directly exercise rights of ownership. I argue that sirkus were not slaves, in fact, but are better understood as institutional dependents whose limited freedom, in comparison with free citizens of a Babylonian town, was a result of their social subordination to an institutional temple household. (Culbertson, 101)

Aside from the naditu and sirkus, a wealthy widow might choose not to remarry, and there were certainly other exceptions to the rule, but, overall, once a young woman was of marriageable age, her father arranged a wedding with an appropriate match considered beneficial to both parties. The marriage agreement was a legal, business contract, having nothing to do with the desires or interests of the betrothed. Scholar Jean Bottero discusses the process:

For a man, marriage was ‘to take possession of one’s wife’ – from the same verb (ahazu) commonly understood for the capture of people or the seizure of any territory or goods. It was the husband-to-be’s family who initiated the matter and who, having chosen the girl, after an agreement paid her family a compensatory amount – in short, a transaction which necessarily brings to mind a form of purchase. After this, the girl thus ‘acquired’, was removed from her own family by the matrimonial ceremony and introduced into her husband’s family where, barring accident, she would stay until she died. (114-115)

There were five steps to the process of marriage, all of which had to be observed in keeping with tradition, that had to be observed precisely for the union to be recognized as legal and binding:

- engagement/marriage contract

- payment of the bride price to the father of the bride and of the dowry to the father of the groom

- ceremony and wedding feast

- bride moves to her father-in-law‘s home

- sexual intercourse the night of the wedding with the expectation the bride would become pregnant

The wife was considered the property of her husband in that she was expected to obey completely and could be divorced and ‘put away’ if her husband chose and had legal grounds (while it was more difficult for a woman to sue for divorce), but, as in all aspects of women’s lives in Mesopotamia, this is understood as a generality. Bottero notes how many women were able to assert themselves and maintain autonomy:

In Mesopotamia, as elsewhere, every woman had up her sleeve two reliable trump cards to stand up to any representative of the so-called ‘strong’ sex, and even to dominate him, in spite of all the customary or legal constraints: first, her femininity; then, her personality, spirit, and character. And it was up to her to make use of these to swim against the opposing current of the contemporary mindset. (118-119)

This seems to be the case in every era of Mesopotamian history but, at the same time, some periods give evidence of greater equality of the sexes overall than others.

Uruk to Early Dynastic Period

The Sumerians of the Uruk and Early Dynastic periods (and, later, the Ur III Period, 2047-1750 BCE) provide the greatest evidence for women’s equality. In the Uruk Period, the cylinder seal was developed, and many from this period belonged to women, suggesting they were legally allowed to sign contracts and enter into business agreements at this time. The Uruk Period also sees the rise of urbanization and the development of writing, both of which make clear that female deities – such as Gula, Inanna, Ninhursag, Nisaba, and Ninkasi among others – were venerated more widely than males.

During the Early Dynastic I Period (2900-2800 BCE), households were associated with the patron deity of the city, which often meant a goddess. Upper-class women had almost equal rights, but lower-class women had few if any (the same applied to men), but during the Early Dynastic II Period (2800-2600 BCE), increased food production led to diversification in the division of labor, providing more opportunities for women as artisans, millers, bakers, brewers, and weavers. Textiles came to be especially associated with women at this time and would continue to be going forward.

TWO WOMEN ARE KNOWN TO HAVE RULED IN THEIR OWN RIGHT DURING THE EARLY DYNASTIC III PERIOD: QUEEN PUABI OF UR & KUBABA OF KISH.

During the Early Dynastic III Period (2600-2334 BCE), women’s status remained the same or improved. Two women are known to have ruled in their own right during this era: Queen Puabi of Ur (known from her tomb in the Royal Cemetery of Ur) and Kubaba of Kish, the only woman’s name to appear as queen in the Sumerian King List (composed c. 2100 BCE). Based on Puabi’s cylinder seal and Kubaba’s name in the King List, both women ruled on their own without a male consort. Queen Barag-irnun of Umma ruled with her husband Gisa-kidu during this same period and was regarded highly enough to have her name included on the dedicatory plaque in the Temple of the god Sara at Umma.

Social mobility was rare but possible as evidenced by Kubaba, who is listed as a former tavernkeeper. There are few records of women (or anyone) climbing the social ladder, but it is clear that many held positions outside the home – besides notable female monarchs, scribes, priestesses, and doctors – working as artists, artisans, bakers, basket makers, brewers, cupbearers, dancers, estate managers, farmers, goldsmiths, jewelry makers, merchants, musicians, perfume makers, potters, prostitutes, tavern owners, and weavers among other occupations.

Akkadian & Ur III Period

Scholars have noted that this model changed under the Akkadian Empire of Sargon the Great and that this is most likely due to his focus on martial strength and conquest coupled with the perception of women as ‘the weaker sex’ in a time when military might became more highly valued. Sargon, and his successors, campaigned regularly against insurgents and break-away regions, keeping a standing army, which also served as a municipal police force. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek comments:

This must have been a highly militarized society, with armed warriors often seen patrolling the streets, particularly in provincial cities, on whose loyalty the center could not always depend. Sargon wrote that every day 5,400 men, perhaps the nucleus of a standing army, took their meal before him in Akkad. (125)

There are fewer records of women holding important positions, but there are also fewer records overall, and modern-day scholars still do not have any idea where Akkad was even located. It does not seem that Sargon had any interest in suppressing women’s rights as he credits his mother with saving him and sending him toward his destiny, invokes Inanna/Ishtar as his personal divine protector, and installed his daughter, Enheduanna, as high priestess of the city of Ur. According to Kriwaczek, offerings to departed priestesses continued to be offered in their honor at Ur long after their deaths (120).

Bottero, and other scholars, cite the Semitic nature of the Akkadian Empire as the reason for women’s decline in status, as males (and male deities) were considered superior to females in every way. This paradigm, however, can also be seen in ancient China, Japan, India, Greece, Rome, and beyond without a Semitic association. In Sargon’s famous inscription found at Nippur, he first cites Inanna before the male gods Anu and Enlil, and Inanna continued to be venerated during the Akkadian Period. It is therefore more likely that any loss of women’s status had to do with a greater value being placed on the traditionally masculine art of war – and deities, usually male, associated with military conquest – as even Inanna is invoked regularly, not as a goddess of love and sexuality, but of warfare.

Babylonians & Assyrians

In the case of the Babylonians, however, the elevation of male gods – especially Marduk – signaled the decline in prestige of female deities and women’s status. Under Hammurabi (also a Semitic monarch), female deities were sidelined by males (the goddess Nisaba, to cite one example, was replaced by the god Nabu as patron of writing), and the Code of Hammurabi strictly regulates women’s behavior and emphasizes the role of woman as a wife and mother. Scholar Stephen Bertman comments:

The belief in the centrality of marriage is clearly expressed in the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi. Of its 282 statutes, almost one fourth are devoted to family law. (275)

Among the laws were those dealing with infidelity or abandonment of the husband by the wife for another man. In such cases, and especially if the two lovers were found together, they were bound to each other and thrown into the river. When they drowned, this was understood as the just judgment of the gods on two people who had violated the central value of marriage and family. A husband could take as many secondary wives as he could afford, however, or even divorce his wife for another woman without the same sort of risk.

The concept of a woman as wife and mother was nothing new, but under Hammurabi, it became more pronounced at the same time as female deities declined in importance. This has led some scholars to the conclusion that there is direct correlation between women’s status and the perceived sex of the deities a community or culture embraces. Even so, it is clear from Hammurabi’s Code that women still had jobs outside the home and continued to find opportunities within the confines of the patriarchal system.

This same model is seen in the Assyrian and Neo-Assyrian periods during which the god Ashur rose to such prominence that he eclipsed all others and his worship bordered on monotheism. Still, the city of Ashur – the site of Ashur’s main temple beginning c. 1900 BCE – traded regularly with the port city of Karum Kanesh, and women were the central administrators and facilitators of this trade. Female administrators (sakintu) supervised the creation and shipment of textiles between Ashur and Karum Kanesh and corresponded regularly with the men who carried the goods between the two cities as well as the merchants who handled sales.

The great Assyrian queen Sammu-Ramat (r. 811-806 BCE) also lived during this period, and her reign is thought to have been so impressive that she inspired the later legendary figure of Queen Semiramis. The Queen Mother Zakutu (l. c. 728 to c. 668 BCE) is another famous woman of the Neo-Assyrian period who rose from the position of secondary wife of Sennacherib (r. 705-681 BCE) to Queen Mother of his successor Esarhaddon (r. 681-669 BCE) and grandmother of Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE), famous for her treaty ensuring her grandson’s smooth succession to the throne.

Persian Women

Persian women were used to equal treatment beginning at least in the Achaemenid period and, most likely, before. Women in ancient Persia received equal pay for their work (which was not the case elsewhere, not even in Sumer), could travel on their own, could own land and businesses, engage in trade, and initiate divorce without complications. Women in the Achaemenid Persian Empire not only worked alongside men but were often supervisors who were paid more than males for managing greater responsibility. Pregnant women received higher wages, and new mothers, for the first month after the birth of their child, did also.

Women in the Achaemenid Empire, Parthia, and the Sassanian Empire were allowed to serve in the military, conduct business as equals with men, and even lead men in battle. In the Sassanian period, female dancers, musicians, and storytellers attained the status of modern-day celebrities, and it is thought that the Sassanian queen Azadokht Shahbanu, wife of Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE) was the power behind the establishment of Gundeshapur, the great cultural center, teaching hospital, and library.

Conclusion

The Sassanian Empire fell to the Muslim Arabs in 651 CE, and women’s status in ancient Mesopotamia declined sharply. This was partly due simply to the conquerors’ attempts at subduing the values of the conquered, as happens in any such situation. In the case of the conquest of Mesopotamia, however, this suppression of the region’s values had a direct correlation to the religion of the conquerors and conquered pertaining to women’s status. The Persian goddess Anahita, though no longer regarded as a deity in her own right and more as an avatar of Ahura Mazda, the supreme deity of Zoroastrianism, was still widely venerated at the time of the conquest and had continued to provide women with a strong image of the divine for centuries.

The Muslim Arab conquest toppled Anahita and other divine feminine figures such as Cybele – the Anatolian mother goddess thought to have been inspired by Queen Kubaba or the semi-divine Semiramis – who were then replaced by the supreme male deity Allah of Islam. This same pattern is evident elsewhere, according to scholars in line with Kramer and Spencer, when patriarchal monotheistic belief systems dominate earlier polytheistic beliefs that celebrate the feminine principle, women’s status in society inevitably suffers and equality is lost.

Questions & Answers

- In ancient Mesopotamia, women could own their own businesses, buy and sell land and slaves, sometimes live on their own, become priestesses, manage estates, and hold jobs outside the home.

- Women in ancient Mesopotamia were expected to become wives, obey their husbands, have children, and tend to the home.

- The most famous woman from ancient Mesopotamia is Enheduanna, the first author in the world known by name. Others include Queen Puabi, Queen Kubaba, and Queen Sammu-Ramat (the inspiration for Semiramis).

- According to some scholars, the decline of women’s rights in ancient Mesopotamia – or any civilization – is a natural result of the rise of a patriarchal religious belief system. In ancient Mesopotamia, women’s rights declined most dramatically after the 651 CE conquest by the Muslim Arabs.

Women in Ancient Egypt

by Joshua J. Mark, the Encyclopedia of World History

Women in ancient Egypt were regarded as the equals of men in every aspect save that of occupation. The man was the head of the household and nation, but women ran the home and contributed to the stability of that nation as artisans, brewers, doctors, musicians, scribes, and many other jobs, sometimes even those involving authority over men.

One of the central values of ancient Egyptian civilization, arguably the central value, was ma’at – the concept of harmony and balance in all aspects of one’s life. This ideal was the most important duty observed by the pharaoh who, as the mediator between the gods and the people, was supposed to be a role model for how one lived a balanced life. Egyptian art, architecture, religious practices, and even governmental agencies all exhibit a perfect symmetry of balance and this can also be seen in gender roles throughout the history of ancient Egyptian civilization.

Scholars Bob Brier and Hoyt Hobbs note how women were equal to men in almost every area except for jobs: “Men fought, ran the government, and managed the farm; women cooked, sewed, and managed the house” (89). Men held positions of authority such as king, governor, general, and a man was considered the head of the household, but, within that patriarchy, women exercised considerable power and independence. Egyptologist Barbara Watterson writes:

In ancient Egypt a woman enjoyed the same rights under the law as a man. What her de jure [rightful entitlement] rights were depended upon her social class not her sex. All landed property descended in the female line, from mother to daughter, on the assumption, perhaps, that maternity is a matter of fact, paternity a matter of opinion. A woman was entitled to administer her own property and dispose of it as she wished. She could buy, sell, be a partner in legal contracts, be executor in wills and witness to legal documents, bring an action at court, and adopt children in her own name. An ancient Egyptian woman was legally capax [competent, capable]. In contrast, an ancient Greek woman was supervised by a kyrios [male guardian] and many Greek women who lived in Egypt during the Ptolemaic Period, observing Egyptian women acting without kyrioi, were encouraged to do so themselves. In short, an ancient Egyptian woman enjoyed greater social standing than many women of other societies, both ancient and modern. (16)

This social standing, however, depended on the support and approval of men and, in some cases, was denied or challenged. It also seems clear that many women were not aware of their rights and so never exercised them. Even so, the respect accorded to women in ancient Egypt is evident in almost every aspect of the civilization from religious beliefs to social customs. The gods were both male and female, and each had their own equally important areas of expertise. Women could marry who they wanted and divorce those who no longer suited them, could hold what jobs they liked – within limits – and travel as they pleased. The earliest creation myths of the culture all emphasize, to greater or lesser degrees, the value of the feminine principle.

The Divine Feminine

In the most popular creation myth, the godAtum lights upon the primordial mound in the midst of the swirling waters of chaos and sets about creating the world. In some versions of this tale, however, it is the goddess Neith who brings creation and, even where Atum is the central character, the primordial waters are personified as Nu and Naunet, a balance of the male and female principles in harmony which combine for the creative act.

Following the creation and beginning of time, women continue to play a pivotal role as evidenced in the equally popular story of Osiris and Isis. This brother and sister couple were said to have ruled the world (that being Egypt) after its creation and to have taught human beings the precepts of civilization, the art of agriculture, and the proper worship of the gods. Osiris is killed by his jealous brother Set, and it is Isis who brings him back to life, who gives birth to his child Horus and raises him to be king, and who, with her sister Nephthys and other goddesses such as Serket and Neith, helps to restore balance to the land.

The goddess Hathor, sent to Earth as the destroyer Sekhmet to punish humans for their transgressions, becomes people’s friend and close companion after getting drunk on beerand waking with a more joyful spirit. Tenenet was the goddess of beer, thought to be the drink of the gods, who provided the people with the recipe and oversaw successful brewing. Seshat was the goddess of the written word and librarians, Tayet the goddess of weaving, and Tefnut the goddess of moisture.

Even the passage of the year was viewed as feminine as personified by Renpet, who notched her palm branch to mark the passage of time. The goddess Bastet, one of the most popular in all of Egypt, was a protector of women, of the home, and of women’s secrets. Egyptian religion honored and elevated the feminine, and so it is hardly surprising that women were important members of the clergy and temple life.

Women & Religion

The most important position a woman could hold, beginning in the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE), was God’s Wife of Amun. There were many “God’s Wives” associated with different deities, and initially, in the Middle Kingdom, the God’s Wife of Amun was simply one among many. The God’s Wife was an honorary title given to a woman (originally of any class but later of the upper class) who would assist the high priest in ceremonies and tend to the god’s statue.

Throughout the New Kingdom of Egypt (1570-1069 BCE) the position increased in prestige until, by the time of the Third Intermediate Period (1069-525 BCE), the God’s Wife of Amun was equal in power to a king and effectively ruled Upper Egypt. During the New Kingdom period, the most famous of the God’s Wives was the female pharaoh Hatshepsut(r. 1479-1458 BCE), but there were many other women to hold the office before and after her.

Women could be scribes and also priests, usually of a cult with a feminine deity. The clergy of Isis, for example, were female and male, while cults with a male deity usually had only male priests (as in the case of Amun). The high prestige of the God’s Wife of Amun, however, is an example of the balance observed by the ancient Egyptians in that the position of the High Priest of Amun was balanced by an equally powerful female.

It must be noted that the designation ‘cult’ in describing ancient Egyptian religion does not carry the same meaning it does in the modern day. A cult in ancient Egypt would be the equivalent of a sect in modern religion. It is also important to recognize that there were no religious services as one would observe them in the present. People interacted with their deities primarily at festivals where women regularly played important roles such as the two virgins who would perform The Lamentations of Isis and Nephthys at the festivals of Osiris.

Priests and priestesses maintained the temples and cared for the statue of the god or goddess, and the people visited the temple to ask for help on various matters, repay debts, give thanks, and seek counsel on problems, decisions, and dream interpretation, but there were no worship services as one would recognize them today. Aside from festivals, people would pray to the gods at home in front of personal shrines, thought to have been erected and kept by women as part of their household responsibilities.

Women were also consulted in dream interpretation. Dreams were considered portals to the afterlife, planes on which the gods and the dead could communicate with the living; they did not always do so plainly, however. Skilled interpreters were required to understand the symbols in the dream and what they meant. Egyptologist Rosalie David comments:

In the Deir el-Medina texts, there are references to ‘wise women’ and the role they played in predicting future events and their causation. It has been suggested that such seers may have been a regular aspect of practical religion in the New Kingdom and possibly even earlier. (281)

These wise women were adept at interpreting dreams and being able to predict the future. The only extant accounts of dreams and their interpretation come from men, Hor of Sebennytos and Ptolemaios, son of Glaukius, (both c. 200 BCE), but inscriptions and fragments indicate that women were primarily consulted in these matters. David continues:

Some temples were reknowned as centres of dream incubation where the petitioner could pass the night in a special building and communicate with the gods or deceased relatives in order to gain insight into the future. (281)

The most famous of these was attached to the Temple of Hathor at Dendera where the clergy was largely female.

Occupations of Women

The clergy of ancient Egypt enjoyed great respect and a comfortable living. History from the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 to c. 2613 BCE) through the Late Period of Ancient Egypt (525-332 BCE) abounds in records of the clergy, especially that of Amun, amassing land and wealth. In order to become a priest, one had to first be a scribe, which required years of dedicated study. Once a woman became a scribe, she could enter the priesthood, go into teaching, or become a physician.

Female doctors were highly respected in ancient Egypt, and the medical school in Alexandria was attended by students from many other countries. The Greek physician Agnodice, denied an education in medicine in Athens because of her sex, studied in Egypt c. 4th century BCE and then returned to her home city disguised as a man to practice.

As the course of study to become a scribe was long and hard, however, not many people – men or women – chose to pursue it. Further, scribes were usually from families of scribes, where great value was placed on literacy and children were expected to follow in their father’s or mother’s occupation. Women, therefore, were regularly employed as weavers, bakers, brewers, professional mourners, sandal-makers, launderers, basket weavers, cooks, waitresses, or as a “Mistress of the House,” known today as an estate owner or property manager. Female brewers and launderers frequently supervised male workers.

When a woman’s husband died, or when they divorced, a woman could keep the home and run it as she liked. This aspect of gender equality is almost astounding when one compares it with women’s rights over just the past 200 years. A widow living in America in the early 19th century, for example, did not have any rights in home ownership and had to depend on a male relative’s intercession to keep her home after the death or departure of her husband. In ancient Egypt, a woman could decide for herself how she would make money and keep her estate in order. Scholar James C. Thompson writes:

There were many ways in which a ‘Mistress of the House” could supplement her income. Some had small vegetable gardens. Many made clothing. One document shows an enterprising woman purchasing a slave for 400 deben. She paid half in clothing and borrowed the rest from her neighbors. It is likely the woman expected to be able to repay the loan by renting out the slave. Indeed, we have a receipt showing that one woman received several garments, a bull, and sixteen goats as payment for 27 days work by her slave. Those who could not raise the money on their own sometimes joined with neighbors to buy a slave. Women were often part of such a consortium. We know that a woman could inherit and operate a large, wealthy estate. A man who owned such an estate would hire a male scribe to manage it and it would seem reasonable that an heiress would do the same thing. We have little evidence of elite women with paying jobs whether full or part time. (3

Especially talented women could also find work as concubines. A concubine was not simply a sex worker but needed to be accomplished in music, conversation, weaving, sewing, fashion, culture, religion, and the arts. This is not to say, however, that their physical appearance did not matter. A request for 40 concubines from Amenhotep III (r. c. 1386-1353 BCE) to a man named Milkilu, Prince of Gezer, makes this clear. Amenhotep III writes:

Behold, I have sent you Hanya, the commissioner of the archers, with merchandise in order to have beautiful concubines, i.e. weavers. Silver, gold, garments, all sort of precious stones, chairs of ebony, as well as all good things, worth 160 deben. In total: forty concubines – the price of every concubine is forty of silver. Therefore, send very beautiful concubines without blemish. (Lewis, 146)

These concubines would have been kept by the pharaoh as part of his harem and, in the case of Amenhotep III, very well kept as his palace at Malkata was among the most opulent in Egypt’s history. The king was considered deserving of many women as long as he remained faithful in caring for his Great Wife, but for most Egyptians, marriage was monogamous and for life.

Love, Sex, & Marriage

As noted above by Watterson, women were considered legally capable in every aspect of their lives and did not require the supervision, consultation, or approval of a man in order to pursue any course of action. This paradigm applied to marriage and sex as well as any other area of one’s life. Women could marry anyone they chose to, marriages were not arranged by the males of the family, and they could divorce when they pleased. There was no stigma attached to divorce, even though a life-long marriage was always regarded as preferable. Brier and Hobbs comment:

Whether rich or poor, any free person had the right to the joys of marriage. Marriage was not a religious matter in Egypt – no ceremony involving a priest took place – but simply a social convention that required an agreement, which is to say a contract, negotiated by the suitor on the family of his prospective wife. The agreement involved an exchange of objects of value on both sides. The suitor offered a sum called the “virginity gift” when appropriate, to compensate the bride for what she would lose, indicating that in ancient times virginity was prized in female brides. The gift did not apply in the case of second marriages, of course, but a “gift to the bride” would be made even in that case. In return, the family of the bride-to-be offered a “gift in order to become a wife”. In many cases, these two gifts were never delivered since the pair soon merged households. However, in the event of divorce, either party could later sue for the agreed gift. (88)

Ancient Egyptian couples also entered into prenuptial agreements which favored the woman. If a man initiated the divorce, he lost all right to sue for the gifts and had to pay a certain sum in alimony to his ex-wife until she either remarried or requested he stop payment. The children of the marriage always went with their mother, and the home, unless it had been owned by the husband’s family, remained with her.

Birth control and abortions were available to married and unmarried women. The Ebers Medical Papyrus, c. 1542 BCE, includes this passage on birth control:

Prescription to make a woman cease to become pregnant for one, two, or three years. Grind together finely a measure of acacia dates with some honey. Moisten seed-wood with the mixture and insert into the vagina. (Lewis, 112)

Even though virginity might have been prized by men initiating marriage, it was not required that a woman be a virgin on her wedding night. A woman’s sexual experience before marriage was not a matter of great concern. The only admonitions concerning female sexuality have to do with women who tempt men away from their wives. This was simply because a stable marriage contributed to a stable community, and so it was in the best interests of all for a couple to remain together. Further, the ancient Egyptians believed that one’s earthly life was only a part of an eternal journey, and one was expected to make one’s life, including one’s marriage, worth experiencing forever.

Reliefs, paintings, and inscriptions depict husbands and wives eating together, dancing, drinking, and working the fields with one another. Even though Egyptian art is highly idealized, it is apparent that many people enjoyed happy marriages and remained together for life. Love poems were extremely popular in Egypt praising the beauty and goodness of one’s girlfriend or wife and swearing eternal love in phrases very like modern love songs:

I shall never be far away from you/While my hand is in your hand/And I shall stroll with you/In every favourite place. (Lewis, 201)

The speakers in these poems are both male and female and address all aspects of romantic love. The Egyptians took great joy in the simplest aspects of life, and one did not have to be royalty to enjoy the company of one’s lover, wife, family, or friends.

Egyptian Queens & Female Influence

Still, there is no denying that Egyptian royalty lived well and the many queens and lesser wives who lived in the palace would have experienced enormous luxury. The palace of Amenhotep III at Malkata, mentioned above, extended over 30,000 square meters (3 hectares) with spacious apartments, conference rooms, audience chambers, a throne room and receiving hall, a festival hall, libraries, gardens, storerooms, kitchens, a harem, and a temple to the god Amun. The palace’s outer walls gleamed brightly white, while the interior colors were a lively blue, golden-yellow, and vibrant green. The women who lived in such palaces experienced a life far above that of the lower classes but still had their duties to fulfill in keeping with ma’at.

Egyptologist Sally-Ann Ashton writes:

In a world that was dominated by the male pharaoh, it is often difficult to comprehend fully the roles of Egyptian queens. A pharaoh would have a number of queens but the most important would be elevated to principal wife. (1)

The role of the principal or Great Wife varied with the pharaoh. Queen Tiye (l. 1398-1338 BCE), the wife of Amenhotep III, regularly took part in the affairs of state, acted as a diplomat, and even had her name written in a cartouche, like a king. Nefertiti (l. c. 1370-1336 BCE), the wife of Akhenaten, cared for their family while also helping her husband run the country. When her husband essentially abandoned his duties as pharaoh to concentrate on his new monotheistic religion, Nefertiti assumed his responsibilities

Great queens are recorded as far back as the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt with Queen Merneith (r. c. 3000 BCE) who ruled as regent for her son Den. Queen Sobeknefru (r. c. 1807-1802 BCE) took the throne during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt and ruled as a woman without regard for the trappings of tradition that only a male could reign over Egypt. Hatshepsut of the 18th Dynasty took Sobeknefru’s example further and had herself crowned pharaoh. Hatshepsut continues to be considered one of the most powerful women of the ancient world and among the greatest pharaohs of Egypt. All these women exerted considerable influence over their husbands, the court, and the country.

Conclusion

WOMEN’S STATUS IN EGYPT WAS INCREDIBLY ADVANCED FOR ANY TIME IN WORLD HISTORY, INCLUDING THE PRESENT.

According to a 2nd-century CE copy of an older legend, when Osiris and Isis ruled over the world at the beginning of time, Isis gave gifts to humanity and, among them, equality between men and women. The meaning of this legend is exemplified through the high status women enjoyed throughout Egypt’s history.

Brier and Hobbs note how “the status of women in Egypt was incredibly advanced for the time” (89). This is no doubt true, but one could argue that women’s status in ancient Egypt was incredibly advanced for any time in world history, including the present. A woman in ancient Egypt had more rights than many women living in the present day.

Equality and respect for women continued through the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 BCE), the last to rule Egypt before it was annexed by Rome. Cleopatra VII (r. 51-30 BCE), the last queen of Egypt, is among the best representatives of women’s equality as she ruled the country far better than the males who preceded her or thought to co-rule with her. Women’s status began to decline in Egypt after it was taken by Rome after her death.

Some scholars, however, date the decline to the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE), noting it only accelerated in Roman Egypt (30 BCE to c. 640 CE). Greco-Roman laws and attitudes toward women, combined with the rise of Christianity in the 4th century which focused the blame for the Fall of Man on women as descendants of Eve, encouraged the belief that women were not to be trusted and needed male guidance and supervision. This decline continued following the Muslim Arab invasion of the 7th century, further challenging the high status Egyptian women had known in the country for over 3,000 years

Questions & Answers

- Women had significant rights in ancient Egypt in every area except occupation. They could own land, buy and sell property, initiate divorce, and were free to travel just as men were. They were not allowed to rule, but there were still several powerful Egyptian queens and high priestesses.

- Women were viewed with great respect in ancient Egypt as evidenced by the many goddesses in the Egyptian pantheon and written accounts of daily life.

- In ancient Egypt, women could be doctors, scribes, priestesses, brewers, basket weavers, dancers, musicians, launderers, artisans, professional mourners, and property managers among many other professions including, in some cases, queen.

- Women’s status in ancient Egypt began to decline in the 4th century CE due to the establishment of Greco-Roman laws and culture combined with the rise of Christianity, which encouraged male superiority. The decline continued in the 7th century CE after the Muslim Arab invasion of Egypt.

Bibliography

- Ashton, S. The Last Queens of Egypt. Routledge, 2003.

- Brier, B & Hobbs, H. Ancient Egypt: Everyday Life in the Land of the Nile. Sterling, 2013.

- David, R. Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt. Penguin Books, 2003.

- Graves-Brown, C. Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt. Continuum, 2010.

- Lewis, J. E. The Mammoth Book of Eyewitness Ancient Egypt. Running Press, 2003.

- Robins, G. Women in Ancient Egypt. Harvard University Press, 1993.

- Shaw, I. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford, 2016.

- Tyldesley, J. Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt. Penguin Books, 1995.

- Watterson, B. The Egyptians. Wiley-Blackwell, 1997.

- Watterson, B. Women in Ancient Egypt. Sutton Publishing Ltd, 1994.

External Links

“Women in Ancient Egypt” by Joshua J. Mark, World History Encyclopedia is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Primary Sources

Law Code of Hammurabi – selected laws related to women, marriage and family.

Created between 2282 – 2248 BCE during the reign of Hammurabi in Babylon.

Translated by C.H.W. Johns, MA, 1903 CE

Full text: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/17150/17150-h/17150-h.htm

- If a man has caused the finger to be pointed against a votary, or a man’s wife, and has not justified himself, that man they shall throw down before the judge and brand his forehead.

- If a man has married a wife and has not laid down her bonds, that woman is no wife.

- If the wife of a man has been caught in lying with another male, one shall bind them and throw them into the waters. If the owner of the wife would save his wife or the king would save his servant (he may).

- If a man has forced the wife of a man who has not known the male and is dwelling in the house of her father, and has lain in her bosom and one has caught him, that man shall be killed, the woman herself shall go free.

- If the wife of a man her husband has accused her, and she has not been caught in lying with another male, she shall swear by God and shall return to her house.

- If a wife of a man on account of another male has had the finger pointed at her, and has not been caught in lying with another male, for her husband she shall plunge into the holy river.

- If a man has been taken captive and in his house there is maintenance, his wife has gone out from her house and entered into the house of another, because that woman has not guarded her body, and has entered into the house of another, one shall p. 26put that woman to account and throw her into the waters.

- If a man has been taken captive and in his house there is no maintenance, and his wife has entered into the house of another, that woman has no blame.

- If a man has been taken captive and in his house there is no maintenance before her, his wife has entered into the house of another and has borne children, afterwards her husband has returned and regained his city, that woman shall return to her bridegroom, the children shall go after their father.

- If a man has left his city and fled, after him his wife has entered the house of another, if that man shall return and has seized his wife, because he hated his city and fled, the wife of the truant shall not return to her husband.

- If a man has set his face to put away his concubine who has borne him children or his wife who has granted him children, to that woman he shall return her her marriage portion and shall give her the usufruct of field, p. 27garden, and goods, and she shall bring up her children. From the time that her children are grown up, from whatever is given to her children they shall give her a share like that of one son, and she shall marry the husband of her choice.

- If a man has put away his bride who has not borne him children, he shall give her money as much as her dowry, and shall pay her the marriage portion which she brought from her father’s house, and shall put her away.

- If there was no dowry, he shall give her one mina of silver for a divorce.

- If he is a poor man, he shall give her one-third of a mina of silver.

- If the wife of a man who is living in the house of her husband has set her face to go out and has acted the fool, has wasted her house, has belittled her husband, one shall put her to account, and if her husband has said, ‘I put her away,’ he shall put her away and she shall go her way, he shall not give her anything for her divorce. If her husband has p. 28not said ‘I put her away,’ her husband shall marry another woman, that woman as a maidservant shall dwell in the house of her husband.

- If a woman hates her husband and has said ‘Thou shalt not possess me,’ one shall enquire into her past what is her lack, and if she has been economical and has no vice, and her husband has gone out and greatly belittled her, that woman has no blame, she shall take her marriage portion and go off to her father’s house.

- If she has not been economical, a goer about, has wasted her house, has belittled her husband, that woman one shall throw her into the waters.

- If a man has espoused a votary, and that votary has given a maid to her husband and has brought up children, that man has set his face to take a concubine, one shall not countenance that man, he shall not take a concubine.

- If a man has espoused a votary, and she has not granted him children and he has set his face to take a concubine, that man shall take a concubine, he shall cause her to enter into his house. That concubine he shall not put on an equality with the wife.

- If a man has espoused a votary, and she has given a maid to her husband and she has borne children, afterwards that maid has made herself equal with her mistress, because she has borne children her mistress shall not sell her for money, she shall put a mark upon her and count her among the maidservants.

- If she has not borne children her mistress may sell her for money.

- If a man has married a wife and a sickness has seized her, he has set his face to marry a second wife, he may marry her, his wife whom the sickness has seized he shall not put her away, in the home she shall dwell, and as long as she lives he shall sustain her.

- If that woman is not content to dwell in the house of her husband, he shall pay her her marriage portion which she brought from her father’s house, and she shall go off.

- If a man to his wife has set aside field, garden, house, or goods, has left her a sealed deed, after her husband her children shall not dispute her, the mother after her to her children whom she loves shall give, to brothers she shall not give.

- If a woman, who is dwelling in the house of a man, her husband has bound himself that she shall not be seized on account of a creditor of her husband’s, has granted a deed, if that man before he married that woman had a debt upon him, the creditor shall not seize his wife, and if that woman before she entered the man’s house had a debt upon her, her creditor shall not seize her husband.

- If from the time that that woman entered into the house of the man a debt has come upon them, both together they shall answer the merchant.

- If a man’s wife on account of another male has caused her husband to be killed, that woman upon a stake one shall set her.

- If a man has known his daughter, that man one shall expel from the city.

- If a man has betrothed a bride to his son and his son has known her, and he afterwards has lain in her bosom and one has caught him, that man one shall bind and cast her into the waters.

- If a man has betrothed a bride to his son and his son has not known her, and he has lain in her bosom, he shall pay her half a mina of silver and shall pay to her whatever she brought from her father’s house, and she shall marry the husband of her choice.

- If a man, after his father, has lain in the bosom of his mother, one shall burn them both of them together.

- If a man, after his father, has been caught in the bosom of her that brought him up, who has borne children, that man shall be cut off from his father’s house.

- If a man who has brought in a present to the house of his father-in-law, has given a dowry, has looked upon another woman, and has said to his father-in-law, ‘Thy daughter I will not marry,’ the father of the daughter shall take to himself all that he brought him.

- If a man has brought in a present to the house of his father-in-law, has given a dowry, and the father of the daughter has said, ‘My daughter I will not give thee,’ he shall make up and return everything that he brought him.

- If a man has brought in a present to the house of his father-in-law, has given a dowry, and a comrade of his has slandered him, his father-in-law has said to the claimant of the wife, ‘My daughter thou shalt not espouse,’ he shall make up and return all that he brought him, and his comrade shall not marry his wife.

- If a man has married a wife and she has borne him children, and that woman has gone to her fate, her father shall have no claim on her marriage portion, her marriage portion is her children’s forsooth.

- If a man has married a wife, and she has not granted him children, that woman has gone to her fate, if his father-in-law has returned p. 33him the dowry that that man brought to the house of his father-in-law, her husband shall have no claim on the marriage portion of that woman, her marriage portion belongs to the house of her father forsooth.

- If his father-in-law has not returned him the dowry, he shall deduct all her dowry from his marriage portion and shall return her marriage portion to the house of her father.

- If a man has apportioned to his son, the first in his eyes, field, garden, and house, has written him a sealed deed, after the father has gone to his fate, when the brothers divide, the present his father gave him he shall take, and over and above he shall share equally in the goods of the father’s house.

- If a man, in addition to the children which he has possessed, has taken a wife, for his young son has not taken a wife, after the father has gone to his fate, when the brothers divide, from the goods of the father’s house to their young brother who has not taken a wife, beside his share, they shall assign him p. 34money as a dowry and shall cause him to take a wife.

- If a man has taken a wife, and she has borne him sons, that woman has gone to her fate, after her, he has taken to himself another woman and she has borne children, afterwards the father has gone to his fate, the children shall not share according to their mothers, they shall take the marriage portions of their mothers and shall share the goods of their father’s house equally.

- If a man has set his face to cut off his son, has said to the judge ‘I will cut off my son,’ the judge shall enquire into his reasons, and if the son has not committed a heavy crime which cuts off from sonship, the father shall not cut off his son from sonship.

- If he has committed against his father a heavy crime which cuts off from sonship, for the first time the judge shall bring back his face; if he has committed a heavy crime for the second time, the father shall cut off his son from sonship.

- If a man his wife has borne him sons, and his maidservant has borne him sons, the father in his lifetime has said to the sons which the maidservant has borne him ‘my sons,’ has numbered them with the sons of his wife, after the father has gone to his fate, the sons of the wife and the sons of the maidservant shall share equally in the goods of the father’s house; the sons that are sons of the wife at the sharing shall choose and take.

- And if the father in his lifetime, to the sons which the maidservant bore him, has not said ‘my sons,’ after the father has gone to his fate the sons of the maid shall not share with the sons of the wife in the goods of the father’s house, one shall assign the maidservant and her sons freedom; the sons of the wife shall have no claim on the sons of the maidservant for servitude, the wife shall take her marriage portion and the settlement which her husband gave her and wrote in a deed for her and shall dwell in the dwelling of her husband, as long as lives she shall enjoy, for money she shall not give, after her they are her sons’ forsooth.

- If her husband did not give her a settlement, one shall pay her her marriage portion, and from the goods of her husband’s house she shall take a share like one son. If her sons worry her to leave the house, the judge shall enquire into her reasons and shall lay the blame on the sons, that woman shall not go out of her husband’s house. If that woman has set her face to leave, the settlement which her husband gave her she shall leave to her sons, the marriage portion from her father’s house she shall take and she shall marry the husband of her choice.

- If that woman where she has entered shall have borne children to her later husband after that woman has died, the former and later sons shall share her marriage portion.

- If she has not borne children to her later husband, the sons of her bridegroom shall take her marriage portion.

- If either the slave of the palace or the slave of the poor man has taken to wife the daughter of a gentleman, and she has borne sons, the owner of the slave shall have no claim on the sons of the daughter of a gentleman for servitude.

- And if a slave of the palace or the slave of a poor man has taken to wife the daughter of a gentleman and, when he married her, with a marriage portion from her father’s house she entered into the house of the slave of the palace, or of the slave of the poor man, and from the time that they started to keep house and acquired property, after either the servant of the palace or the servant of the poor man has gone to his fate, the daughter of the gentleman shall take her marriage portion, and whatever her husband and she from the time they started have acquired one shall divide in two parts and the owner of the slave shall take one-half, the daughter of a gentleman shall take one-half for her children. If the gentleman’s daughter had no marriage portion, whatever her husband and she from the time they started have acquired one shall divide into two parts, and the owner of the slave shall take half, the gentleman’s daughter shall take half for her sons.

- If a widow whose children are young has set her face to enter into the house of another, without consent of a judge she shall not enter. When she enters into the house of another the judge shall enquire into what is left of her former husband’s house, and the house of her former husband to her later husband, and that woman he shall entrust and cause them to receive a deed. They shall keep the house and rear the little ones. Not a utensil shall they give for money. The buyer that has bought a utensil of a widow’s sons shall lose his money and shall return the property to its owners.

- If a lady, votary, or a vowed woman whose father has granted her a marriage portion, has written her a deed, in the deed he has written her has not, however, written her ‘after her wherever is good to her to give,’ has not permitted her all her choice, after the father has gone to his fate, her brothers shall take her field and her garden, and according to the value of her share shall give her corn, oil, and wool, and shall content her heart. If her brothers have not given her corn, oil, and wool according to the value of her share, and have not contented her heart, she shall give her field or her garden to a cultivator, whoever pleases her, and her cultivator shall sustain her. The field, garden, or whatever her father has given her she shall enjoy as long as she lives, she shall not give it for money, she shall not answer to another, her sonship is her brothers’ forsooth.

- If a lady, a votary, or a woman vowed, whose father has granted her a marriage portion, has written her a deed, in the deed he wrote her has written her ‘after her wherever is good to her to give,’ has allowed to her all her choice, after the father has gone to his fate, after her wherever is good to her she shall give, her brothers have no claim on her.

- If a father to his daughter a votary, bride, or vowed woman has not granted a marriage portion, after the father has gone to his fate, she shall share in the goods of the father’s house a share like one son, as p. 40long as she lives she shall enjoy, after her it is her brothers’ forsooth.

- If a father has vowed to God a votary, hierodule, or nu-bar, and has not granted her a marriage portion, after the father has gone to his fate she shall share in the goods of the father’s house one-third of her sonship share and shall enjoy it as long as she lives, after her it is her brothers’ forsooth.

- If a father, to his daughter, a votary of Marduk, of Babylon, has not granted her a marriage portion, has not written her a deed, after the father has gone to his fate, she shall share with her brothers in the goods of the father’s house, one-third of her sonship share, and shall pay no tax; a votary of Marduk, after her, shall give wherever it is good to her.