1 Medicare & Medicaid

“US Healthcare system Chapter 5” by Deanna L. Howe, Andrea L. Dozier, Sheree O. Dickenson, University of North Georgia Press is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

1.1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Compare Original Medicare and the different parts (Part A and Part B) and Medicare Part D with Medicare Advantage, also known as Part C

- Describe the two trust funds that pay for or support Medicare

- Discuss Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

- List two objectives of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

- Discuss four healthcare delivery reforms of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)

- Describe the breakdown of costs for federally-funded healthcare services proposed for federal year (FY) 2020

1.2 KEY TERMS

- Basic Health Program

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

- Medicaid

- Medicare

- Medicare Part A

- Medicare Part B

- Medicare Advantage (Part C)

- Medicare Part D

- Medigap

- Original Medicare

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Affordable Care Act, ACA, Obamacare)

1.3 INTRODUCTION

Healthcare is paid for by federal or state funds, private insurance, or private pay. Health insurance is important to assist with the costs of healthcare but, arguably, most important to provide individuals easier access to healthcare. Most persons aged 65 and older are covered by Medicare, having paid into the Social Security system during employment for at least ten years or forty quarters (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], n.d.). For individuals under 65 years of age and noninstitutionalized, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO, 2018) projected that the majority of individuals (89%) would also have health insurance. Most health insurance for individuals under 65 years of age is from employment-based plans (two thirds). Government and state-subsidized Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) accounts for about one fourth of those with insurance. Others are insured with Medicare, nongroup policies, or other forms (about 4%), leaving 29 million people (11%) uninsured (CBO, 2018). The total cost for government-subsidized healthcare insurance—Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP—was $1.3 trillion in 2016, comprising 38% of all healthcare expenses (Klees et al., 2018). In this chapter, we will explore federal and state-funded health insurance in greater detail. We also look at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and identify services provided by the federal government for the health of all citizens.

1.4 FEDERALLY-FUNDED HEALTHCARE

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is a federal agency within the U.S. government’s Health and Human Services department (HHS). CMS administers and operates the Medicare program. Medicaid, although administered by individual states, also receives oversight by CMS (CMS, n.d.a).

Medicare

Medicare is subsidized health insurance for persons aged 65 or older who are eligible for Social Security, for some individuals who are disabled, and for all patients diagnosed with end-stage renal disease (Congressional Budget Office [CBO], 2018; Klees et al., 2018). Medicare insurance is not automatic for those aged 65 and older; certain actions must be taken and criteria met. For individuals receiving social security benefits, an information packet is sent three months prior to the individual’s 65th birthday, and specific actions must be taken by certain deadlines to obtain Medicare insurance (CMS, n.d.b).

The federal government offers Medicare insurance coverage in two main ways. The choice for the qualified recipient is Original Medicare or Medicare Advantage. Original Medicare is provided directly through Medicare, whereas MedicareAdvantage is provided by private insurance companies (CMS, n.d.b).

Original Medicare includes Part A and Part B. Medicare Part A covers hospitalizations, skilled nursing homes, some skilled nursing home health services after hospitalization, and hospice. Medicare Part B covers physician’s office visits, outpatient care, home health visits without prior hospitalization, medical supplies, and preventive services. Individuals with original Medicare. Part A and Part B, can choose any doctor or healthcare provider and any hospital who accepts Medicare in the U.S., without limitations. Original Medicare pays approximately 80% of costs incurred, and recipients aren’t required to pay a premium for Part A. Premiums aren’t required for Part A because eligible recipients or their spouses paid payroll taxes for Medicare during their working years. A monthly premium is required for part B Medicare, however (CMS, n.d.c).

Medicare Part D, effective as of 2006, provides coverage for prescription drugs (Kirchhoff, 2018). This is a separate plan, and beneficiaries pay a monthly premium. Low-income individuals are eligible for additional assistance (Kirchhoff, 2018). The prescription drug plans have a formulary, and the Medicare Part D beneficiary may have to pay full price if the medication prescribed is not on the formulary or has not received a qualifying formulary exception. Prices have been negotiated to obtain the best prices. Importantly, individuals applying for Medicare Part A and Part B should also apply for Medicare Part D concurrently to avoid a late penalty charge.

Medigap supplemental insurance is an optional insurance bought from private companies for persons with Original Medicare Part A and Part B. Medigap supplemental insurance may pay for some of the costs not covered by Original Medicare—such as copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles—after Original Medicare has paid its part (CMS, n.d.d). Each person with Original Medicare A and B must have their own policy and pay individual monthly premiums for Medigap insurance. Of note, several important healthcare services are not covered by Medigap, such as prescription drug costs (provided under Part D Medicare), purchases of eyeglasses or hearing aids, dental or vision care, private-duty nursing, or long-term care.

Medicare Advantage (also known as Part C or MA Plans) is the second main option for receiving Medicare. With Medicare Advantage, Part A, Part B, and usually Part D are bundled (CMS, n.d.b). Additional benefits, such as dental, hearing, and vision, are also usually offered. Individuals with Medicare Advantage must choose healthcare providers and hospitals within a specific network; using outside providers will result in additional costs. There are monthly premiums. There are several plans to choose from, including the following: Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) plan, Preferred Provider Organization (PPO) plan, Private Fee-for-Service (PFFS) plan, and a Special Needs plan (SNP).

Medicare Advantage Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) plan

With this plan, a primary care provider is chosen within a given network and all services are provided within the network. The exception is emergency care and two out of area services: urgent care and dialysis treatment. A referral is required for any type of specialist. Usually, out of network care may be allowed but may cost more or the beneficiary may be required to pay all the costs. Prescription drugs are usually covered. Prior approval for tests and some services are required and rules must be followed (CMS, n.d.b). There are also HMO Point of Service (HMOPOS) plans within this plan. These HMOPOS plans allow out of network services withthe beneficiary paying higher copayments or having coinsurance (CMS, 2020).

Medicare Advantage Preferred Provider Organization (PPO) plan

This plan is very similar to an HMO but may have a little more flexibility with choosing healthcare providers and agencies within the network, including specialists; a primary care physician is not required. Using providers outside of the network is possible but usually it will cost more. Extra benefits are usually provided, but there are extra costs associated with the benefits (CMS, n.d.b).

Medicare Advantage Private Fee-for-Service (PFFS) plans

With the PFFS plans, the plan dictates the fees for the healthcare providers at the time of service. Choosing a primary care provider is not required and referrals for specialists are not required. Drug costs may or may not be covered. Prior to each healthcare provider visit, the beneficiary must check with the provider to ensure acceptance of the insurance, and copayment is due when the service is provided (CMS, n.d.b).

Special Needs plan

With this plan, persons who have specific healthcare needs, disabilities or diseases with limited income have benefits customized to meet their needs (CMS, 2020). Examples of persons eligible for this type of Medicare plan are persons in nursing homes or other types of institutions, persons eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid, and persons with debilitating conditions, such as chronic heart failure, diabetes, dementia, end-stage renal disease, and HIV/AIDs. A primary care doctor is usually required, and referrals to specialists are also usually required. The plan may or may not cover out-of-network services. Prescription drugs are covered with this plan.

Cost of Medicare

The U.S. Treasury holds two trust funds solely for paying for Medicare; these are a Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund and a Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) trust fund (CMS, n.d.e). The HI trust fund receives money in several ways. Monies are received for the fund through payroll taxes of working individuals, taxes of those receiving Social Security benefits, interest earned through trust fund investments, and Medicare Part A premiums from those who have purchased Medicare Part A but did not meet the eligibility requirements (paying into the system while working) for premium-free Medicare Part A. The SMI trust fund receives the premium payments from recipients of Part B and Part D and funds allocated from Congress and other sources, such as trust fund investment interest (CMS, n.d.e).

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO, 2018, April), Medicare costs in 2017 were $702 billion and accounted for 3.7% of the gross domestic product (GDP); in comparison, defense spending was $590 billion, accounting for 3.1% of the GDP. In 2017, there were over 58 million enrollees in Part A; over 53 million enrollees in Part B; and over 44 million in Part D with the following beneficiary payments in billions: $293.3, $308.6, and $100.1, respectively (Kleeset al., 2018).

Costs to the Medicare Part A recipient in 2020 for a hospitalization of one- to-60 days is a $1408 deductible (CMS, 2020). Medicare Part A also pays for a skilled nursing facility after hospitalization, if needed. If care in a skilled nursing facility is required following hospitalization after 20 days and up to 100 days, Part A pays, but the beneficiary must pay a coinsurance of $176 daily (CMS, 2020). After 100 days, the beneficiary is responsible for all costs (CMS, 2020). Costs for most of the Medicare Part B recipients in 2020 is $144.60 monthly with an additional monthly cost if the beneficiary’s modified adjusted gross income tax is greater than $87,000 (individual) or $174,000 (joint), for the year 2018 (CMS, 2020). The 2020 annual deductible is $198 for all Part B recipients. There is a statutory provision for Social Security recipients called “hold harmless.” This provision prevents the government from charging higher Part B premiums than the Social Security cost of living increase received in that same year. Medicare Part B is paid for by beneficiary premiums (25%) and U.S. Treasury (75%). Calendar year (CY) 2020 spending is expected to total $220 billion (HHS, n.d.). There are monthly premiums for Medicare Part D, with additional monthly fees based on the same income tax numbers as with Part B. Part D yearly deductibles are no more than $435 in 2020 (CMS, n.d.f). There may be a copayment or coinsurance payment for medications after the deductible is met. There is also a coverage gap—“donut-hole”—a temporary limit after $4020 of covered drugs have been spent in 2020. However, after reaching the limits, a large percentage of generic drug prices will be covered by Medicare (in 2020, 75%). As stated previously, individuals who do not sign up for Part D when first eligible are charged. As explained, the costs for Original Medicare have several different parts and programs for seniors to extrapolate, whereas Medicare Advantage has most of these services bundled so may possibly be less confusing.

According to the HHS 2020 budget, Medicare Advantage enrollment is increasing and is expected to total 24 million beneficiaries in calendar year (CY) 2020 (HHS, n.d.a.). This estimated enrollment number will be around 42% of the amount of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Original Medicare, Part A and Part B. HHS reports that access to Medicare Advantage is available to almost all individuals nation-wide and the premiums have remained steady while benefits have increased. Total budget costs for Medicare Advantage are expected to be around $286.5 billion in federal year (FY) 2020.

1.5 JOINT FEDERAL/STATE FUNDED HEALTHCARE

Medicaid, also known as Title XIX of the Social Security Act, was signed into law in 1965 (Klees et al., 2018). Medicaid is funded by the state and federal government jointly with each state administering the program and with the federal government, through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, providing oversight. Medicaid is health insurance for the poor, some elderly, and some disabled persons (CBO, 2018). With Medicaid being administered by states, each state’s eligibility and services covered are different (CMS, n.d.a). Certain benefits are mandatory for each state, however, while others are optional and may vary from state to state. Basic costs such as inpatient or outpatient hospitalization, home health services, and family planning services are some of the mandatory benefits covered. Optional benefits include various occupational, physical, or speech therapies, preventive screenings and rehabilitation services, and hospice. For a full list of mandatory and optional benefits, see Medicaid.gov. For FY 2018, 36,287,063 children were covered by Medicaid (CMS, n.d.e).

Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), also known as Title XXI of the Social Security Act, was signed into law in 1997. CHIP is another jointly- funded program that provides health insurance to those who are poor but whose income is not low enough to meet the Medicaid threshold (CBO, 2018, April). The CHIP and Medicaid programs have been successful in enrolling over 87% of children who are eligible (HHS, 2015). Various acts and laws have been passed by Congress to provide federal allocation of funds through FY 2027 (Klees et al., 2018). For FY 2018, 9,632,367 children were enrolled in CHIP (CMS, n.d.g).

Enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP

As of August 2019, 71,969,720 individuals were enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP nationally, with children representing 50.5% of the total enrollment for both programs. Medicaid enrollment (adults and children) was 65,331,188 individuals. 6,638,532 individuals were enrolled in CHIP. 35,317,330 individuals were enrolled in CHIP or were children in the Medicaid program (CMS, n.d.a). In federal fiscal year (FFY) 2017, there were 46,405,189 children receiving Medicaid and CHIP funds (unduplicated enrollment numbers) compared to45,919,430 in FFY 2018, reflecting a 1% decline from 2017 to 2018 (CMS, n.d.e).

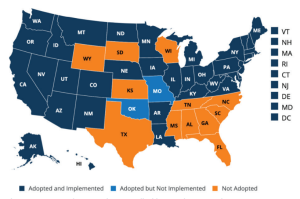

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), signed into legislation in 2010 under President Obama (and therefore often called Obamacare), primarily provided monies (tax credits) to subsidize health insurance coverage for individuals through federal or state government marketplaces as well as expanded Medicaid coverage for individuals with low-income (CBO, May 2018). The ACA also created the Basic Health Program, also known as Medicaid expansion, a program granting states an option to expand Medicaid coverage to individuals in the 138th to 200th percent of the federal poverty guidelines. Through the ACA, states received federal funding “equal to 95% of the subsidies for which those people would otherwise have been eligible through a marketplace” (CBO, 2018, May). Thirty-nine states have chosen to accept this option and are considered Healthcare.gov states (HHS, 2018). The states of Missouri and Oklahoma have adopted the plan but have not yet implemented it; the federal district of Washington, D.C., has implemented the plan (KFF, 2020). (Figure 1.1).

Attribution: Kaiser Family Foundation

License: © Kaiser Family Foundation. Used with permission.

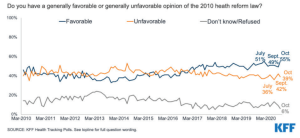

Within the Healthcare.gov states, state level issuers for health plans, essentially insurance companies, received subsidies from the ACA to provide care for the people in the state. In the plan year 2014, there were 187 insurance carriers for the entire conglomerate of Healthcare.gov states; in plan year 2015 and plan year 2016,there were 217 insurance carriers. However, in plan year 2017, there were only 152 carriers; 121 in plan year 2018; and 144 in plan year 2019, thus decreasing. The number of issuers of health plans for each state ranged from one to six, thereby limiting choice of insurance carriers for states with only one insurance carrier. There are also a wide range of costs. The HHS Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) (2018) provided the following information: premiums will increase up to 85% higher in 2019 ($405) compared to 2014 ($218) monthly for the silver plan. The silver plan is the second lowest cost plan and is considered the benchmark plan. Nebraska, the state that has adopted but not implemented the plan, had only one insurance carrier and would have the highest percentage increase ($686 in 2019 compared to $205 in 2014), whereas Indiana, a state with more than one insurance carrier, was slated to have the lowest percentage increase ($280 in 2019 compared to $270 in 2014) (HHS, 2018). Levitt (2020) reports that the ACA is structured so that the highest premium cannot increase above 9.5% of a person’s income, with federal subsidies paying any costs over that amount. Perception of the enactment of the ACA was and remains controversial. The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) tracking poll conducted in October 2020 investigated the favorability view of ACA (Hamel et al., 2020). Participants (1106 voters) show a larger favorable view than unfavorable view. (Figure 1.2).

Attribution: Kaiser Family Foundation

License: © Kaiser Family Foundation. Used with permission.

According to Blumenthal et al. (2015), benefits of the ACA include allowing young adults to be added to their parent’s health insurance policies until the age of 26 years old; providing availability of insurance to young adults, minorities, and the poor; providing quicker access to healthcare providers; and having less complaints about access to care and medical expenses. In addition to expanding health insurance, healthcare delivery reforms were another major component of the ACA (Blumenthal et al., 2015). The reforms include value-based healthcare rather than volume-based healthcare, promotion of healthcare services integration, efforts to boost numbers of and payment to primary care providers, and a responsiveness to the constantly-evolving healthcare environment.

Value-based incentives include decreasing hospital reimbursement for thirty-day readmission rates or occurrence of hospital-acquired infections, with increased funds if certain cost and quality measures were obtained for hospitals as well as physician practices. For promotion of healthcare services integration, organizational arrangements with all parties involved in the care of a patient’s inpatient or outpatient experience are combined, and the organization receives bundled payments for the care episode. By organizing the providers in this manner, the burden of keeping costs low and the quality high is on the healthcare providers within the organization. For those caring for patients with Medicare, savings can be accomplished and then passed on to the providers within the organization. To boost numbers and payment for primary care providers, states were mandated to pay primary care providers Medicare rates when seeing Medicaid patients. Also, funds were provided for scholarships and forgiveness of loans for primary care providers willing to work in underserved areas. In response to the continually evolving healthcare milieu, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) was created to devise and investigate various measures and plans to improve the quality of healthcare and reduce the associated costs (Blumenthal et al., 2015).

According to Kirzinger et al. (2019), a health tracking poll conducted in November 2018 by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) indicated that although the ACA plan remains controversial, many of the ACA provisions are desired by all Americans, regardless of their political persuasion. Those ACA provisions desired by greater than 60% of those surveyed included the following: allow young adults to stay on their parents’ insurance plans until age 26; create health insurance exchanges where small business and people can shop for insurance and compare prices and benefits; provide financial help to low- and moderate-income Americans who don’t obtain insurance through their jobs to help them purchase coverage; gradually close the Medicare prescription drug “donut hole” so people on Medicare will no longer be required to pay the full cost of their medications when they reach the gap; and eliminate out-of-pocket costs for many preventive services (Kirzinger et al., 2019).

Interestingly, overall physician visits have not increased since enactment of the ACA, although there have been more Medicaid patient visits (Gaffney et al., 2019; Johansen & Richardson, 2019). Klein et al. (2017) found similar results with emergency department visits in Maryland. Although the Medicaid population increased by 20% after the implementation of the ACA, there was no significant change in emergency department visits. Expectations were that patients would utilize the new coverage to seek primary healthcare providers.

Kobayashi et al. (2019), assessed patients’ feeling of well-being after receiving greater access to affordable healthcare and found that feelings of well-being did not improve. However, Blumenthal et al. (2015) reported those recently insured were happy with their new coverage. Moreover, 75% of those surveyed had promptly obtained appointments with appropriate healthcare providers and received those appointments in a timely manner within a four-week time period. The costs of healthcare were also reported as a problem less frequently.

Pause and Reflect

Do you know anyone who has received health care through the ACA?

Consider that the Supreme Court heard arguments regarding the constitutionality of ACA, in November 2020. The decision was 7-2 opinion that the challenge to the individual mandate had no standing. Thus, ending the case. Consider how a different opinion could have affected the outcome. Or if, in the future, the ACA is repealed. How should the U.S. government protect those who are uninsured or who lose health insurance? How can the ACA better protect people with pre-existing conditions? Name two advantages and two disadvantages of the Affordable Care Act.

First Person Perspective

Ms. W., M.S.W., has a Concentration in Administration and Public Policy and is a Healthcare Advocate in her community.

Source: Original Work

Attribution: Deanna Howe

License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Growing up in America, my insurance status was always tied to my father’s employment. He was the one to hold the steady job with all the benefits. My mother cycled through employment after having my younger brother and then spent a few years as a caregiver for my ailing grandmother. In my senior year of high school, everything changed. At fifty years old, my father was diagnosed with terminal cancer. It was an immense shock to my family; my parents had one child about to head to college and the other was just twelve years old. They did all they could to continue working and providing for our family, but a year later, my father needed to step away from working to commit himself to the costly and demanding experimental treatment he was undergoing. My father opted into the COBRA program, a costly alternative to ultimate loss of coverage, but my father had a whole treatment team in place within his current network and feared losing his place in the experimental trial he was in. My parents were forced to have a difficult conversation with me about how my mother, brother, and I were all about to lose our health coverage.

At nineteen, I was terrified trying to navigate healthcare on my own, but thankfully my state had just expanded care under the Affordable Care Act. I was one of the many first-time enrollees in the state’s Apple Health through their Health Benefit Exchange. By this time, I was a full-time college student, working part time, and trying to afford a place on my own. Being able to qualify for state Medicaid gave me peace of mind that access to medical care wasn’t something I had to worry about. The same month my insurance coverage began, I came down with the norovirus. I fell ill very quickly while receiving treatment, and I was transported from the urgent care facility to a nearby hospital via ambulance where I was admitted for overnight observation. When I left the hospital, I was terrified of the medical bill I would receive in the mail. I knew I could never afford it, but thankfully that bill never came. To this day, I am grateful for the access to needed services that the expansion of the Affordable Care Act has afforded me. I was able to access coverage through a job for a few years, but when I decided to go back to school for my master’s degree, I had comfort knowing that I would once again be able to access care. No one should have to choose between getting the medical care they need and being able to provide a clear path for their future. Thanks to Washington state’s commitment to expand Medicaid under the ACA ten years ago, I am able to share this with you today. First person perspective vignette collected and created by Deanna Howe, 2020 For your consideration: Ms. W. describes the fear of having to navigate the unfamiliar territory of finding health insurance. Her state is one of many which provide access to expanded Medicaid health services. If you were a voter, would you vote in favor or against ACA Medicaid expansion? Why or why not? For college students who are unable to remain covered under a parent’s plan, should the government offer an insurance protection benefit under the ACA? Consider what would have happened to Ms. W. had ACA insurance coverage not been available to her during the illness she described. What financial implications might Ms. W. face?

First person perspective vignette collected and created by Deanna Howe, 2020.

1.6 FEDERALLY FUNDED ORGANIZATIONS FOR THE PROMOTION OF HEALTH

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

The mission of Health and Human Services (HHS) is “to enhance and protect the health and well-being of all Americans by providing for effective health and human services and by fostering sound, sustained advances in the sciences underlying medicine, public health, and social services” (HHS, n.d., p.2). There are nine divisions and more than 100 programs provided by HHS. The nine divisions are as follows: the Administration for Children and Families, the Administration for Community Living (ACL), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (which has subsumed the previous stand-alone Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Indian Health Service, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (which has subsumed the previous stand-alone Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ]), and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

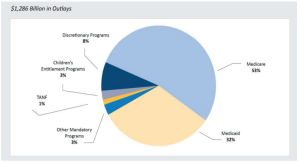

The FY 2020 Budget allocates $1,286 billion for all of HHS programs and services. The $1,286 billion is divided as follows: 53% for Medicare; 32% for Medicaid; 8% for discretionary programs; 3% for children’s entitlement programs; 3% for other mandatory programs; and 1% for temporary assistance for needy families (TANF) (HHS, n.d., p. 2) (Figure 1.4).

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)

The mission of the CMS is as follows: “The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services supports innovative approaches to improve quality, accessibility, and affordability” (HHS, n.d., p. 49). As stated previously, the CMS funds, administers, and operates the Medicare program and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation agency. Medicaid and CHIP, although administered by individual states, also receives funds and is overseen by CMS (HHS, n.d.). The FY 2020 budget proposal requests $60.5 billion over the 2019 budget and is expecting a savings of $954.1 billion due to changes made and being made. The priorities for the CMS as outlined in the 2020 budget (HHS, n.d.) are reducing prescription drug costs, transforming the healthcare system to one that pays for quality and outcomes (value-based care), combating the opioid crisis, and reforming America’s health insurance system (pp. 65–67). To decrease drug costs, reforms are focused on improving competition, negotiating for better prices, providing incentives for lower list prices, and lowering out-of-pocket costs for patients (HHS, n.d.).

To transform the healthcare system to one that pays for quality and outcomes, some of the reforms include allowing accrediting bodies of hospitals and other healthcare facilities to release accrediting surveys. Also, several hospital-required quality programs will be consolidated to one program, thus decreasing regulatory burden. There is an effort throughout the plan to provide equitable payments to all parties involved in healthcare who provide the same type of services. To reform America’s health insurance system, several proposals make Medicare payments more equivalent to the private pay market, provide greater choices for beneficiaries, and encourage innovation at the consumer and state level. Consolidation of medical school payments for physicians and reforms for medical liability are also planned.

The Food and Drug Administration

The Food and Drug Administration’s (n.d.) mission statement is as follows:

The Food and Drug Administrations’ (FDA) is responsible for protecting the public health by assuring the safety, efficacy, and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products, medical devices, the nation’s food supply, cosmetics, and products that emit radiation. FDA also advances the public health by helping to speed innovations that make medicines more effective, safer, and affordable; and by helping the public get the accurate, science-based information they need to use medicines and foods to maintain and improve their health. Furthermore, FDA has responsibility for regulating the manufacturing, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products to protect the public health and to reduce tobacco use by minors. Finally, FDA plays a significant role in the nation’s counterterrorism capability by ensuring the security of the food supply and fostering development of medical products to respond to deliberate naturally emerging public health threats. (Para. 1)

Advancing innovations for effective, safe, and affordable medication and medical devices; foods safety; management of tobacco products; and counterterrorism are priorities for the FDA. A highlight for FY 2018 was setting a record for approving the most generic medications in a single year (971), compared to a five-year average of 771 generics approved per year. In addition, the FDA provided for the emergency approval and authorization for COVID-19 vaccines in 2020. This action paved the way for an early campaign to provide protection to millions of U.S. citizens as well as persons throughout the world.

The Health Resources and Services Administration

The mission of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) is the following:

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) is the primary federal agency for improving healthcare to people who are geographically isolated, economically or medically vulnerable. HRSA works to improve health through access to quality services, a skilled health workforce and innovative programs. (HHS, n.d., p. 16)

Funds are provided for primary health centers, increasing the healthcare workforce in areas of shortage, funds for reducing maternal mortality and child health, and HIV/AIDs programs. Healthcare systems, such as Poison Control and Organ Transplant, and healthcare systems in rural areas are also provided funds.

The Indian Health Service

“The mission of the Indian Health Service is to raise the physical, mental, social, and spiritual health of American Indians and Alaska Natives to the highest level” (HHS, n.d., p. 22). Funds are provided to expand healthcare and provide facilities for the American Indian population. Preventive health services and special programs, such as for diabetes education, are examples of other areas receiving funds.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The mission statement for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is multifaceted. The mission statement is as follows:

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) works 24/7 to protect America from health, safety, and security threats, both foreign and in the United States. Whether diseases start at home or abroad, are chronic or acute, curable or preventable, human error or deliberate attack, CDC fights disease and supports communities and citizens to do the same. CDC increase(s) the health security of our nation. As the nation’s health protection agency, CDC saves lives and protects people from health threats. To accomplish its mission, CDC conducts critical science and provides health information that protects our nation against expensive and dangerous health threats, and responds when these arise. (HHS, n.d., p. 27)

Some of the funds provided are for such preventative strategies as immunizations; prevention of such diseases as HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted diseases and tuberculosis; and health promotion. Some funds are for management of chronic diseases, such as high blood pressure and diabetes. Recently, because of the rise in opioid addictions and overdoses in the U.S., the opioid epidemic has been a focus of the CDC. More recently and presently, viruses such as the coronavirus have taken center stage. Occupational safety and health, environmental health, overall public health preparedness, and global health are also critical areas of emphasis.

The National Institutes of Health

According to HHS, “The National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) mission is to seek fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior of living systems and the application of that knowledge to enhance health, lengthen life, and reduce illness and disability” (HHS, n.d., p. 37). Some of the research priorities for 2020 include the opioid crisis, neonatal abstinence syndrome, chronic pain, and childhood cancer. The quality and safety of healthcare, precision medicine, and health services research are other priorities.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

The mission statement of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration is the following: “The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) reduces the impact of substance abuse and mental illness in America’s communities” (HHS, n.d., p. 45). Funds for this department support community mental health services, children’s mental health services, and behavioral health clinics. The mental health needs of students, substance abuse prevention and treatment, and suicide prevention programs are also priorities.

The Administration for Children and Families

According to HHS, “The mission of the Administration for Children and Families promotes the economic and social well-being of children, youth, families, and communities, focusing particular attention on populations such as children in low-income families, refugees, and Native Americans” (HHS, n.d., p. 100). The Administration for Children and Families’ proposed 2020 budget provides funds for the following in descending order: temporary assistance for needy families; Head Start; Child Care and Development Fund; foster care and permanency; child support enforcement; and refugee and entrant assistance. These departments provide monies for vulnerable populations, such as those needing temporary financial assistance, child abuse victims, human trafficking victims, runaways and homeless individuals, and for foster care. Funds are provided with goals to improve the lives of low-income families, especially through early childhood programs and childcare.

The Administration for Community Living (ACL)

The mission of the Administration for Community Living is: “The Administration for Community Living maximizes the independence, well-being, and health of older adults, people with disabilities across the lifespan, and their families and caregivers” (HHS, n.d., p. 116). The ACL provides monies for nutritious meals to senior centers and homebound individuals. Monies are also provided to fight elder abuse and neglect, Alzheimer’s disease, and disability programs.

The Office of the Secretary

The Office of the Secretary, though not a division, is responsible for oversight of all HHS programs. These several staff divisions, agencies, and programs report directly to the Secretary for HHS:

1. Office of the Secretary, General Departmental Management. “The General Departmental Management budget line supports the Secretary’s role as chief policy officer and general manager of the department” (HHS, n.d., p. 120).

2. Office of the Secretary, Opioids and Serious Mental Illness. This is a new office and was developed as a result of 64,000 deaths to drug overdoses in 2016 (HHS, n.d.).

3. Office of the Secretary, Office of Medicare Hearings and Appeals. The Office of Medicare Hearings and Appeals provides a forum for the adjudication of Medicare appeals for beneficiaries and other parties. “This mission is carried out by a cadre of Administrative Law Judges exercising decisional independence under the Administrative Procedures Act with the support of a professional, legal, and administrative staff” (HHS, n.d., p. 124).

4. Office of the Secretary, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). The mission of this office is “To help lower healthcare costs, empower consumer choice, and improve provider satisfaction, ONC will work to make health information more accessible, decrease the documentation burden, and support electronic health records’ usability” (HHS, n.d., p. 126).

5. Office of the Secretary, Office for Civil Rights (OCR). The mission of this office is as follows: “The Office for Civil Rights is the Department’s chief law enforcer and regulator of civil rights, conscience and religious freedom, and health information privacy and security” (HHS, n.d., p. 128).

6. Office of Inspector General. “The mission of the Office of Inspector General is to protect the integrity of Department of Health and Human Services programs as well as the health and welfare of the people they serve” (HHS, n.d., p. 130).

7. Public Health and Social Services Emergency Fund (PHSSEF). The mission of this office is as follows: “The Public Health and Social Services Emergency Fund directly supports the nation’s ability to prepare for, respond to, and recover from the health consequences of naturally occurring and man-made threats” (HHS, n.d., p. 133).

1.7 SUMMARY

This chapter has explored federally funded healthcare (Medicare) and jointly federal/state funded healthcare (Medicaid and CHIP). It looked at the costs of the programs. It described the Affordable Care Act and it has discussed other federally funded programs provided through the HHS.

1.8 REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. How would you explain the difference between the Medicare choices to someone close to retirement age?

2. How is Medicare funded?

3. During what circumstances can Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program be utilized?

4. What are two objectives of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act?

5. What are four healthcare delivery reforms of the Affordable Care Act?

6. How are the FY 2020 HHS budget funds allocated?